Inside factories and cleanrooms across the country, preparations for Artemis 2 are in full swing. Scheduled to launch in just over a year, the first crewed flight of the Artemis program will send astronauts to fly by the Moon for the first time in five decades. While the mission’s daring objectives can make it seem like a distant goal, in reality, its launch date is rapidly approaching. Mission commander Reid Wiseman recently described the crew’s training flow to AmericaSpace in extensive detail. While Wiseman’s crew prepares for their flight, NASA’s priority is manufacturing a safe vehicle for them to fly in. This article provides an update on the preparations for the mission.

Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover, Christina Koch, and Jeremy Hansen will live inside an Orion capsule, which will, in turn, be propelled into deep space by a towering SLS rocket. The SLS/Orion stack consists of four primary elements. The Core Stage, the largest single rocket stage ever built, is flanked by twin Solid Rocket Boosters. These components have extensive heritage from the Space Shuttle program, and they will provide the thrust required to lift Orion into orbit. Once the Core Stage separates, a fully-fueled Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage (ICPS) will provide a final propulsive boost to loft Orion into an elliptical high Earth orbit. Orion itself is perched on top of these elements. The ICPS was completed last year. Over the past month, NASA has made significant progress on the final assembly of the remaining three components of the rocket. They are essentially complete and ready for a fast-paced stacking operation and launch campaign which will take place next year.

Each SLS Solid Rocket Booster (SRB) includes five segments, which are bolted together inside NASA’s Vehicle Assembly Building. They are the most powerful solid rocket motors ever built for flight. Unlike their liquid-fueled cousins, SRBs can be loaded with propellant up to five years before their launch date because their fuel cannot evaporate. The process has more in common with casting plastic toys with a mold than with pumping gasoline into a car. The SRB segments for Artemis 2 were cast in 2019. To load an SRB, engineers pour a caustic slurry of ammonium perchlorate, atomized aluminum powder, and assorted binding agents into a cylindrical steel casing. Within a handful of days, this mixture cures into a solid.

Once they were cast, the Artemis 2 SRB segments were placed in storage at Northrop Grumman’s factory in Promontory, Utah. With the Artemis 2 launch campaign approaching, NASA decided to ship them to the Kennedy Space Center last month. The booster segments were loaded onto a train, which arrived in Florida on September 24th. While they instantly produce 7 million pounds of thrust when ignited, the SRBs are extremely stable and can be transported safely by rail. The segments are being stored inside a dedicated facility at KSC, while they will wait to be stacked next February. During the intervening three months, technicians will paint the iconic “worm” logo onto the two center segments of the boosters. They will also bolt nozzles and conical skirts onto the two aft segments, which will shield the rest of the SLS from booster exhaust at liftoff.

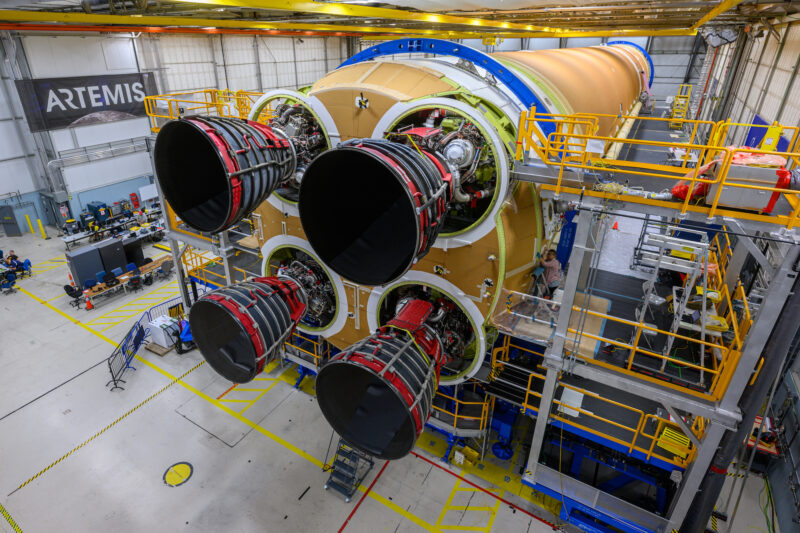

At 212 feet in length, the SLS Core Stage is the second-longest rocket stage ever built. Teams at the Michoud Assembly Facility in Louisiana completed the Core Stage on September 24th by installing the last of its four RS-25 engines. The liquid hydrogen-powered RS-25 is the most efficient rocket engine in operation. It is also one of the most reliable; during 135 Shuttle missions, only one RS-25 failed during flight, and that engine shut down due to a sensor error rather than to a problem with the engine itself. When the Shuttles were sent to museums in 2012, they were outfitted with detailed RS-25 replicas in place of their actual main engines. One of the engines powering Artemis 2 was used on 15 flights and was taken from Endeavour. Another flew five flights and was taken from Atlantis. The remaining two engines were built from scratch to support the Artemis program.

The engines were installed over the span of two weeks in September. Each motor was lifted into a narrow chamber by a specialized forklift and bolted in place. Technicians at Michoud are currently connecting their myriad propellant and electrical lines to the Core Stage’s propellant tanks. Once this process is complete, the stage will be essentially ready for flight. NASA anticipates shipping it to the Kennedy Space Center in December. While its delivery date was delayed from the original target date of March 2023 due to a supply chain issue, it will still arrive in Florida two months before it is needed.

The pacing item for the Artemis 2 launch schedule has always been the Orion spacecraft. As there was originally supposed to be a three-year gap between the first two Artemis missions, the capsule was dependent upon reused avionics from the Artemis 1 capsule. This preceding mission experienced a year’s worth of delays. As a result, the final assembly of the Artemis 2 Orion could not be completed until Artemis 1 returned to Earth last December. The curtains had barely closed on that mission when work on the next spacecraft, nicknamed “The Ship” by its builders, intensified. Engineers transplanted eight avionics boxes from the Artemis 1 Orion to its younger sibling. As soon as this work was completed, the new capsule received its blunt heat shield and its tiled backshell panels.

Thanks to the Orion team’s hard work, the capsule was essentially complete when Wiseman, Glover, Koch, and Hansen visited KSC in August. However, it is just half of the vehicle which will carry the quartet of astronauts to the Moon. The European Service Module, built in Bremen, Germany through an international partnership with Airbus, arrived in Florida last October. It carries Orion’s main engine, solar panels, propellant tanks, and nitrogen and oxygen for the crew to breathe.

On October 19th, the Artemis 2 Crew Module was lifted atop the Service Module. The vital electrical and life support conduits which link the two vehicles were then fitted together. It is worth noting that the completion of Orion took slightly longer than anticipated. The two modules were originally scheduled to be mated in mid-September [1]. The one-month delay to the procedure suggests that the Artemis 2 launch date might slip into December of 2024 or early 2025. However, it was still an eyewatering moment for the Artemis program. The completed spacecraft will be home to Wiseman, Glover, Koch, and Hansen during their ten-day mission. Beyond that, Orion was the final major element of the Artemis 2 stack to reach completion. Final preparations for the launch of Artemis 2 can now begin in earnest.

The shipment of the SRBs, the completion of the Core Stage, and the final assembly of Orion are discrete events. However, when viewed together, these closely-spaced milestones provide evidence that Artemis 2 is rapidly approaching. While spacecraft are ultimately just agglomerations of metal and wiring, they mean so much more to the people who design, build, and fly them. In many cases, they take on their own “personalities” in the eyes of their creators. That is particularly true of the Artemis 2 rocket and spacecraft, which will take center stage in the eyes of the world as Wiseman, Glover, Koch, and Hansen make history next winter. Thousands of Americans pored years of their lives into the SLS and Orion, and they have every reason to be proud of their recent accomplishments.

The SLS core stage is the second largest rocket stage ever built. It is 212 feet long and 27.6 feet in diameter. The Space X Super Heavy booster is 226 feet long and 29.5 feet in diameter.

Hi Ron,

Good catch. My apologies for the error – I must have been thinking of how this statistic was phrased before April’s Starship test flight. Super Heavy is, indeed, a longer stage (unless you consider the Launch Vehicle Stage Adapter to be part of the Core Stage, since the two components remain attached throughout flight).

Neither stage is the widest. That title goes to the first stage of the Soviet N-1, which was 56 feet wide. At 33 feet in diameter, the Saturn V first and second stages were the widest to complete their mission.

Best regards,

Alex

SLS, like the shuttle External Tank, could get to orbit with a smaller payload…stage-and-a-half style.

That needs looking at.

New Horizons exaggerated the tyranny of the rocket in a different way.

Simply stretching the SLS core with a modest Mars sample return… might that shove the SLS core to the Moon with the light payload coasting to Mars?