Ten years ago, this month, Space Shuttle Discovery thundered into orbit for one of the most complex construction missions ever flown to the International Space Station (ISS). Commander Mark Polansky, Pilot Bill Oefelein, and Mission Specialists Nick Patrick, Bob “Beamer” Curbeam, Joan Higginbotham, and Sweden’s first astronaut, Christer Fuglesang—joined by Expedition 14 crew member Sunita Williams for ascent and Germany’s Thomas Reiter for descent—spent almost eight days at the station, delivering a huge amount of cargo and supplies. They also executed four spacewalks to install a new component for the Integrated Truss Structure (ITS) and re-wired the station’s electrical power system. In so doing, Fuglesang became Sweden’s first spacewalker, Curbeam became the most EVA-experienced African-American astronaut, and Oefelein became the first person to blog from orbit. Their mission had begun its days long before the Columbia accident and had evolved considerably by the time Discovery eventually reached space.

In fact, STS-116 was less than six months away from flight when Columbia disintegrated during re-entry on 1 February 2003. At the time of the disaster, Shuttle Atlantis would have launched on 24 July to deliver the cube-shaped P-5 truss, as well as additional payloads, aboard a single Spacehab cargo module. As its name implied, P-5 was part of the “Port” side of the station’s huge Integrated Truss Structure (ITS) of solar arrays, batteries, and radiators. Measuring 11 feet (3.3 meters) long, 15 feet (4.5 meters) wide, and 14 feet (3.2 meters) high, and weighing around 4,100 pounds (1,860 kg), P-5 was affectionately nicknamed “Puny” by the STS-116 crew. It served as a structural “spacer” to separate the giant Solar Array Wings (SAWs) of the P-4 and P-6 truss segments. The P-6 hardware had been launched on STS-97 in late 2000 and temporarily situated on the “top” (or “zenith”) of the space station, but it was intended that after the installation of P-5 it would be relocated to its permanent position at the furthest-port side of the ITS.

Additionally, in the days before the loss of Columbia, STS-116’s crew would rotate two ISS increments, with Expedition 7 Commander Yuri Malenchenko and Flight Engineers Aleksandr Kaleri and Ed Lu returning from a four-month mission and Expedition 8 Commander Mike Foale and Flight Engineers Bill McArthur and Valeri Tokarev replacing them for six months aboard the orbiting outpost. Meanwhile, the “core” STS-116 crew of Commander Terry Wilcutt, Pilot Bill Oefelein, and Mission Specialists Christer Fuglesang—destined to become Sweden’s first man in space—and Bob “Beamer” Curbeam was formally announced by NASA in February 2002.

For Oefelein and Fuglesang, it would be their first spaceflights; Wilcutt and Curbeam, by contrast, had five previous space shuttle missions between them. “It was late on a Friday afternoon and I got a call to come down to the corner office,” Oefelein remembered later. “The corner office is the boss’s office. Well, this is going to go one of two ways: it’s either going to be really good or really bad!” When he arrived at the office of Chief Astronaut Charlie Precourt, he saw Terry Wilcutt already there and remembered only a handful of words from the next half-hour of conversation. Sworn to secrecy until after the media announcement, the hardest part for Oefelein was keeping quiet from everyone outside his immediate family for the next several days.

The tragedy of Columbia led to a multi-year suspension of space shuttle operations, and it was not until July 2005 that the fleet returned to flight. By that point, STS-116 had been realigned as a six-person crew. Wilcutt was replaced by Mark Polansky, who would be embarking on his second space voyage and his first in the Commander’s seat. The revised crew announcement came in February 2005, with a projected launch in spring 2006. Joining Polansky would be Oefelein, Fuglesang, and Curbeam from the original STS-116 team, together with “rookie” astronauts Joan Higginbotham and British-born Nick Patrick as Mission Specialists. For Higginbotham, it came as something of a surprise, for she had already been announced in summer 2002 as a member of the STS-117 crew. “I had been with my other crewmates for two years,” she recalled, “and I thought that’s pretty much how we’re going to launch in that crew configuration.” Patrick, on the other hand, had been unassigned at the time of Columbia. In addition to a “huge mix of emotions,” his main feeling was relief at having finally been selected as part of a shuttle crew.

Also aboard for STS-116 would be a Shuttle Rotating Expedition Crewmember (ShREC). NASA astronaut Sunita Williams would fly to the ISS to begin a six-month increment, whilst Germany’s Thomas Reiter—flying on behalf of the European Space Agency (ESA)—would take her seat for the return to Earth, wrapping up 5.5 months in orbit. “Probably the most significant thing for us to exchange Thomas Reiter for Suni Williams is that we’re back in business,” said Curbeam before the flight. “This is how we intended to do business.”

Even before Columbia was lost, the basic emblem for the STS-116 crew patch had been sketched out. The northern origins of Alaska-born Oefelein and Sweden’s Fuglesang were represented on the patch, with the North Star taken from the Alaska State Flag. A juxtaposition of the Stars and Stripes and the blue field and yellow Scandinavian Cross also took pride of place. Although the shuttle returned to nominal operations in July 2005, further instances of foam liberation from the External Tank (ET)—the principal root cause of the Columbia accident—prompted further delays and the fleet did not fly again until July 2006. This correspondingly pushed other downstream missions further to the right, and STS-116 ended up tracking a target launch date just before Christmas 2006.

Roaring into the night at 8:47 p.m. EST on 9 December, Discovery’s rise to orbit marked the first shuttle launch in the hours of darkness for more than four years. “And liftoff of the Space Shuttle Discovery,” came the announcer’s words, “lighting up the nighttime sky as we continue building the International Space Station.” At the time of launch, the station—then occupied by Expedition 14 Commander Mike Lopez-Alegria of NASA, together with his crewmates Mikhail Tyurin of Russia and Thomas Reiter—was orbiting about 220 miles (350 km) above the south coast of England, near Southampton.

Flying for the first time on STS-116 was the Advanced Health Management System (AHMS), developed by NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in Huntsville, Ala. During the 8.5-minute “burn” of Discovery’s three Space Shuttle Main Engines (SSMEs), the AHMS served in “monitor-only” mode to continuously collect and process accelerometer data from the turbopumps. It was intended that the new system would provide greater insight into the health of the two most risky SSME components—the High Pressure Fuel Turbopump and High Pressure Oxidizer Turbopump—both of which operated at around 30,000 revolutions per minute.

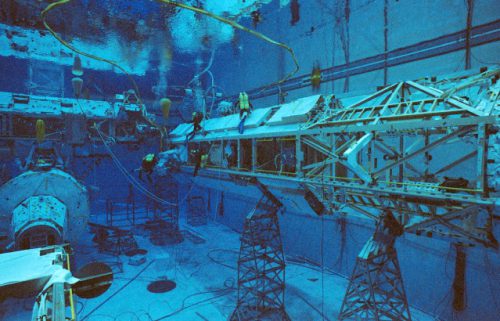

Upon achieving an initial orbit of 142 miles (228 km), inclined 51.6 degrees to the equator, the crew set to work configuring Discovery for orbital operations and Patrick led the effort to open the shuttle’s payload bay doors. As Polansky and Oefelein oversaw an intricate sequence of rendezvous maneuvers to reach the ISS on the third day of the mission, the remainder of the crew prepared rendezvous tools, installed a centerline camera in Discovery’s docking system window, and extended the docking system’s outer ring. Curbeam and Fuglesang also checked out their Extravehicular Mobility Units (EMUs). Meanwhile, the Orbiter Boom Sensor System (OBSS) conducted a series of inspections of the Reinforced Carbon Carbon (RCC) areas of the shuttle’s wing leading edges and nose. The OBSS was then stowed and the Canadian-built Remote Manipulator System (RMS) mechanical arm was employed to examine the crew cabin and the environs of the two Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) pods.

Rendezvous operations got underway shortly before midday EST on 11 December, and the Terminal Initiation (TI) burn was executed at a distance of about 9 miles (15 km) “behind” the station a couple of hours later. This positioned Discovery around 600 feet (180 meters) below the ISS by mid-afternoon, after which Polansky executed a nine-minute Rendezvous Pitch Maneuver (RPM) backflip to allow Lopez-Alegria and Tyurin to photograph Discovery’s heat shield. Based at the windows of the Zvezda service module, Lopez-Alegria and Tyurin fired off digital images of the shuttle’s fuselage with 400 mm and 800 mm lenses, allowing resolutions as fine as 1 inch (2.5 cm) and 3 inches (7.6 cm).

Docking at Pressurized Mating Adapter (PMA)-2, at the forward-facing end of the U.S. Destiny lab, occurred at 5:12 p.m. EST. A little over 90 minutes later, following customary pressurization and leak checks, the hatches were opened and Polansky’s crew floated aboard the orbiting outpost, creating a crew of 10 astronauts and cosmonauts from four sovereign nations, the United States, Russia, Germany, and Sweden. After the customary safety briefings, Sunita Williams transferred her custom seat liner over to the Soyuz TMA-9 spacecraft, docked at the aft end of the station. This would provide Lopez-Alegria, Tyurin, and Williams with an escape vehicle in the event that an emergency forced them to evacuate the ISS. In tandem, Reiter officially became a member of Discovery’s crew for the return to Earth, later in December.

But before that return to Earth, a complex mission with several unexpected twists and turns lay ahead.

The second part of this article will appear tomorrow.

Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace