Twenty years ago, this month, an American national record-breaker circled high above Earth, aboard Russia’s Mir space station. In July 1996, Shannon Lucid had surpassed Norm Thagard to become the most flight-experienced U.S. spacefarer and by early September she had eclipsed Russian cosmonaut Yelena Kondakova to become the most seasoned female spacefarer of all time. Not for another decade would her record for womankind be beaten. And in September 1996, after a stupendous 188 days in orbit on a single mission—and 223 days across the entirety of her five-flight astronaut career—Lucid returned to Earth aboard Space Shuttle Atlantis. Yet her return home was far from the “end,” but rather the beginning of more than two years of continuous U.S. presence aboard the station, for riding uphill with Atlantis’ STS-79 astronauts was another long-duration Mir resident, Lucid’s old friend and former crewmate John Blaha.

Launched to Mir aboard Atlantis on STS-76 in March 1996, it was not NASA’s or Russia’s intent to keep Lucid aboard the station for so long. In fact, she was scheduled to return to Earth on 9 August, after 140 days, which would still have positioned her ahead of Thagard on the U.S. national experience table, though somewhat short of Kondakova’s 169-day empirical record for woman. However, following Columbia’s STS-78 launch in June 1996, NASA found worrisome damage to the field joint of the Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs), apparently caused by the leakage of hot gases through a total of six discrete joints. It was a catastrophic “blow-by” of the booster’s rubberized O-ring seals which had caused the loss of Challenger in January 1986. Upon close inspection, it was found that the gas-path in the case of STS-78’s boosters had not penetrated their capture joints and, correspondingly, the SRBs had performed within their design requirements.

However, the issue raised concerns over new adhesives and cleaning fluids which had recently been added to the boosters to meet Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) guidelines. Since the EPA forbade the usage of an old-style methyl-based adhesive, NASA was keenly aware that the development of a replacement would take time. Space Shuttle Program Manager Tommy Holloway noted that it was “a serious situation until we determine it’s not serious,” but added that the SRB joints were an order of magnitude more robust than those which doomed Challenger.

Atlantis’ launch on STS-79 was postponed from 31 July until no sooner than mid-September and the stack was rolled back to the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) for repairs. In the meantime, Lucid set to work conducting an inventory of Mir’s Spektr and newly-arrived Priroda modules, in order to prepare the way for her successor, John Blaha. She also packed experiments, data tapes, and equipment, ready for transfer to Atlantis when the shuttle eventually arrived. In fact, although three previous shuttle crews had docked with the space station, STS-79 would be the first to do so with the complete Mir, outfitted with all six research and habitation modules.

And the STS-79 astronauts—Commander Bill Readdy, Pilot Terry Wilcutt, and Mission Specialists Jay Apt, Tom Akers, and Carl Walz—were also trailblazers, in that they would carry the first Spacehab “double” logistics module in Atlantis’ payload bay. Although the flat-roofed Spacehab facility had flown several times on the shuttle, firstly in mid-1993, it had previously been carried in a single configuration and primarily for scientific research. Following its maiden voyage, Spacehab, Inc. had signed a $54 million contract with NASA to change its mode of operations to logistics and resupply for Mir flights. The company invested an additional $15 million into the fabrication of a double module, using one of two single modules, attached via an adapter ring to a Structural Test Article (STA). The double module had the capability to transport up to 6,000 pounds (2,720 kg), whilst a system of canvas soft stowage bags increased the maximum capacity to almost 9,000 pounds (4,080 kg).

In March 1996, STS-76 flew the first Spacehab single logistics module, with its double counterpart expected to ride STS-79. The forward section of the double module would house experiments to be performed during the 10-day shuttle mission itself, whilst the rear section housed the logistics and supplies for Mir. Soft stowage bags were arrayed on the “walls” and “floor” of the aft part of the module, with colored labels to indicate their destination: pink for items going to Mir, blue for items coming back from Mir, and white for items which would stay aboard Atlantis throughout the flight. In orbit, the bags reminded the STS-79 crew of a herd of sea-cows.

All told, Bill Readdy’s crew would transfer around 4,000 pounds (1,800 kg) of supplies into Mir, including logistics, food, and water generated by the shuttle’s fuel cells. Several key pieces of research hardware would also head across the hatch into the space station. These included the Biotechnology System (BTS) for cartilage development studies, the Materials in Devices and Superconductors (MIDAS) to examine the electrical properties of high-temperature materials and the Commercial Generic Bioprocessing Apparatus (CGBA) with its self-contained aquarium. By the time Atlantis undocked, she also removed over 2,000 pounds (900 kg) of experiment samples and equipment, thereby achieving a new record for the largest total logistics transfer to and from Mir.

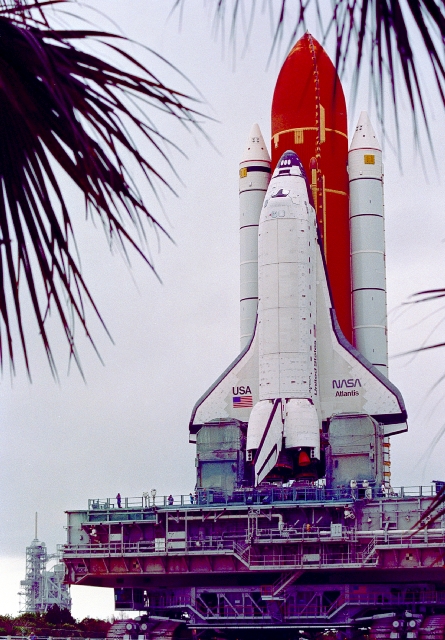

Early in September 1996, the STS-79 stack was returned to Pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida, ready for a launch at mid-month. In fact, it was the third time that Atlantis had completed the journey from the VAB to the pad that summer. She was originally rolled out on 1 July, but after the discovery of the STS-78 booster anomalies, a rollback was ordered. The urgency of this rollback intensified in readiness for the expected landfall of Hurricane Bertha. By mid-July, plans had evolved to replace both of STS-79’s boosters, but on the 25th the right-hand replacement SRB failed a leak check at the junction between its aft-center and forward-center segments. It later became clear that an applicator bristle brush, in the vicinity of the secondary O-ring, was the root cause of leakage. New O-rings were installed and the booster was restacked and leak-tested, without incident.

Atlantis returned to the pad in the third week of August, but with Bertha having dissipated the arrival of Hurricane Fran threatened Central Florida and on 4 September the STS-79 stack headed back to the VAB. Its time there, however, was brief. Within 24 hours, Atlantis was back on the pad, with only a slight delay beyond its original 14 September target launch date. Now scheduled to fly on the 16th, the crew was awakened late the previous evening and marched smartly through preparations to fly. Without further ado, Atlantis rocketed into orbit, precisely on time, at 4:54 a.m. EDT. The stage was set for a two-day rendezvous, several days of joint activities with Mir’s incumbent crew of Commander Valeri Korzun and Flight Engineer Aleksandr Kaleri … and Shannon Lucid’s long-awaited return to Earth.

The second part of this article will appear tomorrow.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace