When NASA and its worldwide partners began assembling the International Space Station (ISS) in low-Earth orbit in the late winter of 1998, it was possible to conduct the early tasks with a combination of spacewalks and robotics. The shuttle’s Canadian-built Remote Manipulator System (RMS) mechanical arm—first trialed on STS-2 in November 1981—had been utilized over the years for a multitude of tasks, ranging from satellite deployment and retrieval to the maneuvering of spacewalking astronauts, and was ideally suited for ISS assembly work. It had assisted with the installation of the station’s Unity node, its Destiny lab, and the first electricity-generating set of U.S.-built solar arrays. But by the spring of 2001, the fledgling outpost was becoming so large that shuttle-based robotics were no longer able to accomplish the task alone.

Canada had been a long-standing partner in the station program, virtually from its conception as Space Station Freedom in the mid-1980s, and had developed the Space Station Remote Manipulator System (SSRMS), also known as “Canadarm2.” Measuring 57.7 feet (17.6 meters) in length, the “Big Arm” was about 12.5 percent longer and more than four times heavier than its shuttle cousin. Through the unique presence of two “wrist” joints and two “hands,” it was able to “inchworm” along the ISS structure by interfacing with Power and Data Grapple Fixtures (PDGFs).

For launch, Canadarm2’s components were folded onto a Spacelab pallet in the shuttle’s payload bay. “We had to bend it in pieces,” explained James Middleton, vice president of business development of MD Robotics, who led the Canadarm2 engineering team for the Canadian Space Agency (CSA). “How to fasten it down was a very complex design process. To be able to hold it in a manner that the loads were adequately relieved during the shuttle launch was a tough challenge.” Its importance to the station was profound, and Canadarm2 was correspondingly inserted into the early stages of the construction manifest, on shuttle assembly mission 6A. That mission, STS-100, whose crew included Canada’s first spacewalker, Chris Hadfield, launched 15 years ago, in April 2001.

In addition to Hadfield, the STS-100 crew included Commander Kent Rominger, Pilot Jeff Ashby, and Mission Specialists Scott Parazynski and John Phillips, together with Italian astronaut Umberto Guidoni and Russia’s Yuri Lonchakov. As outlined in yesterday’s AmericaSpace history article, this made it the first mission in history to carry representatives of as many as four discrete nations. On 22 April 2001, the crew was awakened to the sound of the late Canadian folk musician and singer-songwriter Stan Rogers, as Hadfield and Parazynski prepared for the first of a pair of EVAs to install Canadarm2 onto its orbital home for at least the next two decades. In doing so, Hadfield would admit Canada into an exclusive “club” of spacewalking nations which, at the time, comprised just six other members: the former Soviet Union, the United States, France, Germany, Japan, and Switzerland.

Launched three days earlier, Rominger and Ashby had docked Shuttle Endeavour smoothly onto the forward-facing Pressurized Mating Adapter (PMA)-2 interface of the U.S. Destiny lab on 21 April. However, despite exchanging a few tools and other items of hardware, they would not meet the station’s incumbent Expedition 2 crew—which comprised Commander Yuri Usachev of Russia and NASA astronauts Jim Voss and Susan Helms—until later in the joint mission. This was due to the fact that Endeavour’s cabin pressure had been lowered from its normal 14.7 psi level to just 10.2 psi, in support of the first EVA.

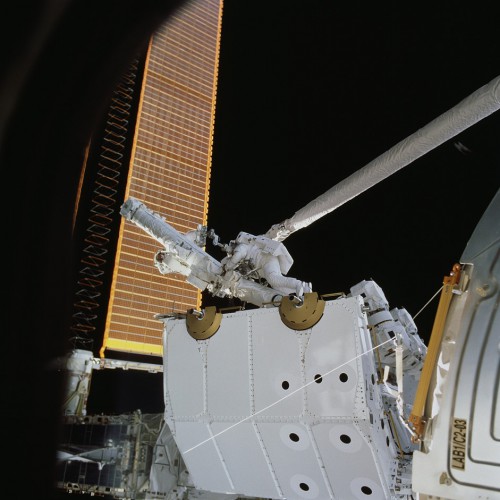

The spacewalk got underway at 7:45 a.m. EDT on 22 April, with Hadfield designated “EV1,” with red stripes on the legs of his space suit for identification, and Parazynski in a pure white suit as “EV2.” Hadfield had been in training for the 6A assembly tasks for almost four years by this stage, and the duo quickly set to work. Working from inside the shuttle, Ashby and Guidoni used Endeavour’s RMS arm to detach a Spacelab pallet from the payload bay and latch it to a cradle atop the Destiny lab. Aboard this pallet was the 3,970-pound (1,800-kg) Canadarm2, as well as an Ultra-High Frequency (UHF) antenna to enable space-to-space communications on future EVAs and between the shuttle and the ISS.

Within the first two hours, Hadfield and Parazynski had successfully attached the UHF antenna onto Destiny, before turning to their next major objective: the installation of Canadarm2 itself. With Hadfield working on the RMS and Parazynski “free-floating,” they released four cables to provide power, commanding, and video to and from the Flight Support Equipment Grapple Fixture (FSEGF) on the pallet, which would provide the Big Arm’s early base on the space station. Parazynski connected these cables to Destiny, which enabled Canadarm2 to be controlled via a Robotics Workstation (RWS) inside the lab.

With the UHF antenna installation behind them, the spacewalkers removed insulating blankets from the elements of the Big Arm and released 32 small “jackbolts,” then eight large “super bolts.” This allowed them, by 11 a.m. EDT, to deploy the arm’s main boom and a few minutes later they were in position to begin unfolding its second boom. Next, they employed a Pistol Grip Tool (PGT) to secure expandable diameter fasteners, which kept the two booms rigidized. Hadfield and Parazynski wrapped up their EVA, cleaned up their work site, and returned inside Endeavour at 2:55 p.m. EDT, after a spacewalk which had lasted seven hours and 10 minutes. This placed it just inside the Top 25 longest EVAs of all time, at that point in history. At around the same time, from inside Destiny, Voss and Helms successfully commanded the first motion of Canadarm2.

“It really just opens the door to what all of us can be doing here internationally,” said Hadfield, “beginning to explore space as a planet.” Fellow Canadian astronaut Steve MacLean offered a message of congratulations, and the national anthem “O, Canada” was played in Hadfield’s honor. And the international element to which Hadfield alluded was further reinforced the next day, 23 April, when Endeavour’s RMS was employed by Parazynski to remove the Italian-built Raffaello Multi-Purpose Logistics Module (MPLM) from the payload bay and install it onto the Earth-facing (or “nadir”) port of the Unity node. Raffaello was one of three reusable MPLMs—the others being Leonardo and Donatello—which were intended to support cargo deliveries aboard visiting shuttle flights. Between the first flight of Leonardo on STS-102 in March 2011 and the final flight of Raffaello on STS-135 in July 2011, MPLMs were launched on no fewer than 12 occasions. Donatello ultimately never flew, but Raffaello would fly four times and Leonardo eight times, including its eventual installation on the ISS as the Permanent Multipurpose Module (PMM).

By this time, the cabin pressure aboard the shuttle had been raised to 14.7 psi, allowing for the opening of hatches into the space station at 5:25 a.m. EDT. This allowed the 10 astronauts and cosmonauts to exchange hugs and handshakes in orbit for the first time. It was, however, a busy time. At 7:13 a.m., Helms commanded Canadarm2 to begin a three-hour “walk-off” from the Spacelab pallet and onto Destiny. In essence, the Big Arm “switched ends,” with the lab’s PDGF becoming its new base. In the meantime, supplies were transferred between the shuttle and station, ahead of a hatch closure at 3:26 p.m. This separation of the two crews was necessary as the shuttle’s cabin pressure was again reduced to 10.2 psi, preparatory to EVA-2 on 24 April.

Hadfield and Parazynski next ventured outside the shuttle at 8:34 a.m. EDT, kicking off a spacewalk which ran to seven hours and 40 minutes. On this occasion, their roles were reversed, with Parazynski perched at the end of Endeavour’s RMS arm and Hadfield in a free-floating configuration. The pair opened a panel on the Destiny lab’s exterior, enabling Parazynski to hook up power, data, and video cables and establish connections for the PDGF circuits. Despite the early failure of a backup power circuit, the spacewalkers and Expedition 2 crew member Susan Helms were able to access another connector and complete the redundant power path to the Big Arm.

This posed one of several instances of frustration, exacerbated when an electrical connector cover got away from Hadfield as he worked to remove the 100-pound (45-kg) Early Communications antenna. The errant connector lodged itself behind a thermal cover at the starboard Common Berthing Mechanism (CBM) on the Unity node—precisely where the Quest airlock was due to be installed later in 2001—and after a fruitless search Hadfield was called away to complete other work. The errant connector was not expected to affect future operations. The EVA ended at 4:15 p.m. EDT, bringing the total experience of Canada’s first spacewalker to 14 hours and 50 minutes. At the time of writing, only three Canadians have performed extravehicular activity, with Hadfield now sitting in second place on the experience table, behind Dave Williams and ahead of Steve MacLean.

So successful were the first two EVAs that a provisional third spacewalk—set aside for 26 April—proved unnecessary. “If it is needed,” NASA stressed in its STS-100 press kit, “its activities will be planned during Endeavour’s flight.” With EVA-3 unnecessary, the crews were presented with an additional day of cargo transfer operations between the shuttle and ISS. Led by Umberto Guidoni, the Raffaello MPLM was swiftly unloaded of almost 4,000 pounds (1,800 kg) of equipment, supplies, and scientific facilities for the station. Specifically, two Expedite the Processing of Experiments to the Space Station (ExPrESS) racks were delivered, for the accommodation of multiple future payloads. One of these racks was equipped with the ActiveRack Isolation System (ARIS), enabling it to be isolated from vibrations elsewhere on the ISS. Additionally, on its first flight, the Raffaello MPLM also carried four Resupply Stowage Racks (RSRs) and four Resupply Stowage Platforms (RSPs) for activation and augmentation.

As with any shuttle mission, and in spite of the spectacular success of the Canadarm2 installation effort, not everything ran according to plan. Late on 25 April, one of the station’s three Command & Control (C&C) computers sustained a failure. Communications and data-transfer capability between the ISS and the Space Station Flight Control Room (FCR) at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas, was lost, but routed through Endeavour, which allowed the crew and mission controllers to talk to each other. Over the course of a day or so, C&C No. 1 was brought back into service and STS-100 itself received a 48-hour extension of its docked phase to assist with the recovery effort and complete the remaining joint activities. The latter included the loading of around 1,600 pounds (725 kg) of material to be brought back to Earth, and the Raffaello MPLM was returned to Endeavour’s payload bay on the afternoon of 27 April.

Next day, at 5:02 p.m. EDT, Susan Helms performed Canadarm2’s first major hardware relocation, as she manipulated the 3,000-pound (1,360-kg) Spacelab pallet from Destiny and back aboard the shuttle for its return to Earth. At the controls of Endeavour’s RMS to receive the pallet was Chris Hadfield. The event marked the first-ever robotic-to-robotic transfer in space, as well as the last major task of STS-100. At 1:34 p.m. EDT on 29 April, Endeavour undocked smoothly from the space station to begin her return journey to Earth. Cloud cover, showers, and gusty winds at the Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida ultimately forced a decision to bring the shuttle home to Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., and Rominger and Ashby guided their ship to a safe touchdown in ideal weather conditions at 9:11 a.m. PDT (12:11 p.m. EDT). STS-100 had traveled over 4.9 million miles (7.9 million km) and completed 186 orbits in just shy of 12 days in space.

The mission was over, but for Canadarm2 it was merely the beginning of an impressive career in space which continues to this day. The robotic “hand-off” of the Spacelab pallet by Helms and Hadfield was very much a dress rehearsal for the kind of work which the Big Arm would perform in the next few years, as the ISS grew ever larger. Two months later, in July 2001, Canadarm2 was instrumental in the installation of the Quest airlock onto the starboard interface of the Unity node.

Its accomplishments over the following decade included the completion of the station’s expansive Integrated Truss Structure (ITS)—laden with electricity-generating solar arrays, radiators, and batteries—and the activation of pressurized and unpressurized components from NASA and its international partners. Its Mobile Base System (MBS) and Mobile Transporter (MT) were added to the station in 2002 and its “Dextre” Special Purpose Dextrous Manipulator (SPDM) “hand” was installed in 2008, providing for a vastly expanded range of capabilities for Canadarm2.

Last February, it received a major “lube job” on its Latching End Effector (LEE) and associated hardware by Expedition 42 spacewalker Terry Virts, as well as successfully transferring the Leonardo PMM from the Unity nadir port to its current position on the Tranquility node. Since 2009, the Big Arm has performed 18 “Cosmic Catches” of unpiloted visiting vehicles: five Japanese H-II Transfer Vehicles (HTVs), eight SpaceX Dragons, and five Orbital ATK Cygnuses. It has also proven indispensable for spacewalking and undoubtedly will remain the centerpiece of ISS robotics for the remainder of its operational lifetime, currently anticipated to run through at least 2024.

This is part of a series of history articles, which will appear each weekend, barring any major news stories. Next week’s article will focus on the 25th anniversary of STS-39, the first unclassified Department of Defense mission by the Space Shuttle and the longest military flight of the 30-year shuttle program.

Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Great Story. More pictures would be the icing on the cake..Thank you Mr.Evan

edit…for Icing on the cake.