Two decades ago, today, on 27 March 1996, a pair of white-suited astronauts clambered outside Shuttle Atlantis and became the first Americans to perform a spacewalk outside an Earth-circling space station in almost a quarter-century. Although more than 30 EVAs had been undertaken from shuttle airlocks since April 1983—including the spectacular repair and servicing of Solar Max and the Hubble Space Telescope (HST)—it had not been since the twilight of the Skylab era that U.S. citizens had spacewalked outside a space station. Yet the six-hour EVA by STS-76 astronauts Linda Godwin and Rich Clifford, 20 years ago, was just one of a handful of records to be set on the mission which Commander Kevin Chilton had nicknamed “The Spirit of ’76.”

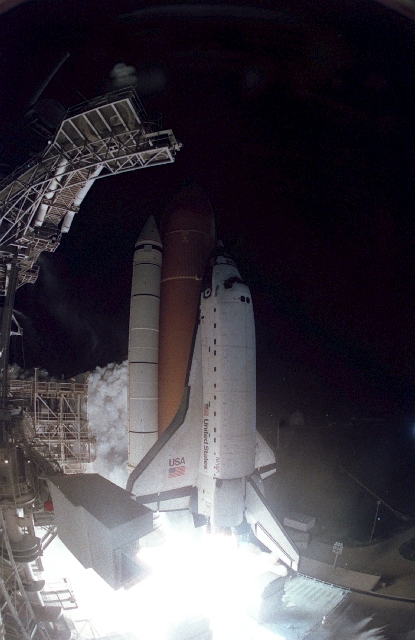

Following a 24-hour delay, caused by high winds and rough seas off Cape Canaveral, which threatened to violate the Return to Launch Site (RTLS) contingency abort limits, Atlantis and her six-member crew—Commander Chilton, together with Pilot Rick Searfoss, Mission Specialist Ron Sega, future Mir resident Shannon Lucid, as well as Godwin and Clifford—roared into the night at 3:13:04 a.m. EDT on 22 March 1996. As described in yesterday’s AmericaSpace history article, theirs was the third docking mission between a shuttle and Mir, following on the heels of STS-71 in June 1995 and STS-74 in November 1995. It was also the fourth shuttle flight to rendezvous with the Russian orbital outpost, taking into account the STS-63 “Near Mir” flyby in February 1995.

Atlantis’ liftoff on her 16th mission—approaching the midpoint of what would turn out to be a spectacular 33-flight career—had proceeded with exceptional smoothness, save for a minor hydraulic fluid leak and STS-76 achieved orbit about 15,000 miles (24,260 km) “behind” Mir, closing at about 800 miles (1,300 km) with each circuit of the globe. Over the course of their first 24 hours in orbit, Chilton and Searfoss executed several rendezvous and phasing “burns” to make further gains on their quarry, whilst the remainder of the crew set to work activating experiments and hardware in the first Spacehab logistics module and readied the Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU) space suits for the EVA. Late on 23 March, Chilton performed the Terminal Initiation (TI) burn and, after receiving authorization to proceed from both U.S. and Russian flight controllers, performed a perfect docking with Mir at 9:34 p.m. EDT. Barely 42 hours had elapsed since Atlantis left Earth.

“Coming up to dock with Mir, approaching that tremendously large piece of machinery, it goes from being a very bright light to looking like a spider,” Clifford told a Smithsonian interviewer, years later. “Then, all of a sudden, the station’s huge solar power array looks like it’s 10 inches from your window!” It was fortunate, Clifford mused, that Atlantis was not slightly off-axis. Approaching slowly, he hardly felt a thing at the point of contact and capture. Chilton, at the aft flight deck controls, was totally absorbed in the proximity operations and docking; so much so that when Clifford tapped him on the shoulder and offered congratulations, the commander jumped in surprise. “You can even see it on the video,” said Clifford. “He was just so focused on the docking.”

After capture, Clifford worked to pressurize the docking mechanism and hatches were opened to a flurry of handshakes, hugs, and laughter as the STS-76 crew met the incumbent Mir crew of Russian cosmonauts Yuri Onufrienko and Yuri Usachev. Traditional gifts of memorabilia, shirts, and chocolate Easter bunnies were exchanged, and Atlantis’ crew gave Onufrienko and Usachev copies of Jim Lovell’s book Lost Moon, upon which the 1995 movie Apollo 13 was based.

With five days of joint activities ahead of them, no time was wasted in transferring equipment and supplies between the Spacehab module and Mir. The 33-foot-long (10-meter) tunnel linking the middeck to the Spacehab provided the opportunity for a spot of impromptu space gymnastics, according to Rich Clifford. “We took a large rubber band, called a Dyna-Band,” he recalled, “that we used for exercise and stretched it across the airlock hatch on the middeck. Then we’d shoot ourselves down the tunnel. We had a competition to see who could do it without touching the tunnel walls. Nobody ever made it.”

Significantly, Shannon Lucid became an official member of the Mir-21 crew at 8:30 a.m. EDT on 24 March, when the custom-molded seat liner that she would use in the event of a contingency landing was transferred to the Soyuz TM-23 descent module. To mark the event, STS-76 Flight Director Bill Reeves and Russian Flight Director Nikolai Nikoforov issued a joint “Go” statement. As transfer activities continued between the shuttle and the space station, the crew managed to spot the recently-discovered Comet Hyakutake, which would go on to make one of the closest cometary passes to Earth in 200 years. Its blue-green coma was at its most visible on 24 March, and it made its closest approach to Earth about 24 hours later, temporarily eclipsing Hale-Bopp as the “Great Comet of 1996.” At one stage, on the 26th, the STS-76 crew told journalists that Hyakutake was so brilliant that they could see it almost from horizon to horizon.

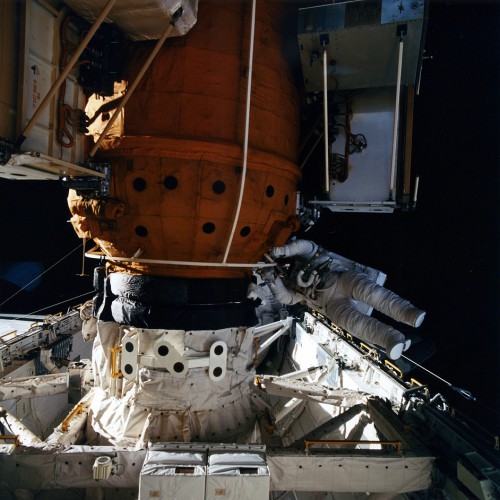

Later that day, preparations entered high gear for Godwin and Clifford’s EVA and the hatches between Atlantis and Mir were closed, as was the hatch to the Spacehab module. Godwin—who became only the third American woman to make a spacewalk, as well as the first female to serve in the lead spacewalker (EV1) role—and Clifford departed the airlock at 1:36 a.m. EDT on 27 March and spent six hours and two minutes in the vacuum of space. As the first U.S. EVA outside a space station since the Skylab era, the sheer size of Mir came as something of a surprise.

The Weightless Environment Training Facility (WETF) at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas, had not been big enough to hold a full-size mockup of the station’s docking module and, in Godwin’s words, the STS-76 crew “had to pretend a lot in training.” During underwater simulations, for example, she and Clifford left the airlock mockup and were carried by divers to a docking module mockup, lying on its side, although they were able to utilize virtual reality techniques to gain perspective for translating along its length. Spacewalking outside Mir was also novel in that the shuttle’s standard safety tethers were not large enough to attach onto the station’s handrails, which required the spacewalkers to use new hooks and a foot restraint.

Unlike the floodlit payload bay of the orbiter, Mir also provided little illumination, with the exception of its flashing running lights, and it was often difficult to see in the gloom. Setting up their worksite outside Mir, Godwin and Clifford first attached clamps and securely installed the four experiments of the Mir Environmental Effects Payload (MEEP) into place for its 18 months of operations. They also used cable cutters to remove the television camera from the docking module, which was returned to Earth aboard Atlantis. Inside Mir itself, Onufrienko, Usachev, and Lucid caught a few fleeting glimpses of the progress of the EVA, through the airlock hatch of the station’s Kvant-2 module and a slightly better view through one of the cabin portholes in the base block.

Interestingly, as explained by Bryan Burrough in his book Dragonfly, Godwin and Clifford were explicitly forbidden to venture away from the DM and onto the structure of Mir itself, due to the “pin cushion” of experiments affixed to the exterior of Kristall and the sprouting, sharp-edged solar arrays and protruding solar sensors. “They said it wasn’t safe,” Clifford was quoted by Burrough. “There are appendages all over Kristall. Some of them were visibly sharp. Snag points. Sharp edges. Not a clear translation path.”

Spacewalking offered other challenges, too. “The hand work can be fatiguing on a spacewalk,” Godwin pointed out, years later, and driven by adrenaline, it was not until she returned inside Atlantis that the realization—That was a long day—finally dawned on her. “On some of these really long EVAs, you don’t get anything to eat from the time you suit up until you take your helmet off, and that can be ten hours! You start thinking about it after a while. You look inside and see the crew eating. Of course, there’s no reason for the people inside to starve out of sympathy. It’s also tiring for the people inside. There’s a mental focus that doesn’t let up for hours, making sure they’re on the procedures and that they’re not leaving anything out or losing anything.”

With the EVA behind them, the time came for what Chilton described as “a bittersweet moment”: the point to trade goodbyes with Onufrienko, Usachev, and Lucid, close the hatches, and prepare for undocking and departure. During their five days together, about 1,500 pounds (680 kg) of water and almost 4,000 pounds (1,800 kg) of scientific equipment, logistics, and supplies had been transferred from Atlantis to Mir.

“It will be sad to say farewell to such a good team,” said Onufrienko at one stage. The hatches were closed at 8:15 a.m. EDT on 28 March and, following pressurization and other checks, Atlantis and Mir parted company almost exactly 12 hours later, at 8:08 p.m. After Chilton maneuvered the shuttle to a safe distance, Rick Searfoss took control for the standard flyaround inspection and was profoundly impressed by the “chameleon-like” appearance of Mir. “I was enthralled,” he said later, “by the constantly changing and indescribably beautiful hues of white, tan, gold and blue.” One hour after undocking, Chilton and Searfoss lowered their orbit and steadily increased their separation distance from the station.

By this stage, the likelihood of rain and clouds over the Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida on the morning of 31 March had obliged Mission Control to instruct the crew to prepare for a landing about 24 hours earlier than planned, at 7:57 a.m. EDT on the 30th. Predictions for a touchdown on the 30th included light winds and scattered clouds, but generally acceptable weather conditions.

In anticipation for the early landing, Chilton, Searfoss and Clifford checked out Atlantis’ systems and flight surfaces, but NASA revealed that they would use a circulation pump instead of the Auxiliary Power Units (APUs) to route hydraulic fluid to the ailerons, elevons, speed brake, and rudder during re-entry. APUs No. 1 and 2 were activated as normal, but since APU No. 3 had been associated with the hydraulic fluid leakage during ascent, it was to be brought to life late in the re-entry and used only as a backup if necessary. Elsewhere, Godwin completed work in the Spacehab module and closed the hatch.

As circumstances transpired, both landing opportunities at KSC on 30 March—the first at 7:57 a.m., the second at 9:33 a.m.—were called off, due to weather conditions which meteorologists described as “too dynamic” to be acceptable. Following the decision to delay by 24 hours, the crew began reactivating systems, but hit trouble when reopening the payload bay doors. Microswitches showed that the position of a set of centerline latches for the doors was not fully open, which prevented the opening process. Godwin compared the latch positions and described them as appearing to be fully open. Mission Control asked the astronauts to use manual deployment switches and the door opened properly.

For the remainder of 30 March, they conducted Earth observations, preparatory to a second attempt in the early hours of the 31st. With more stable weather expected at Edwards Air Force Base in California, it was decided to forego the two KSC landing opportunities on the 31st. Chilton and Searfoss pulsed the Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) thrusters for the irreversible burn at 7:25 a.m. EDT, committing the shuttle to an hour-long hypersonic descent into the “sensible” atmosphere, heading for a touchdown at Edwards. Atlantis touched down smoothly, a few minutes before local sunrise, at 5:29 a.m. PDT (8:29 a.m. EDT), wrapping up a nine-day flight and the start of an American human presence in space which would endure for the next 27 months.

This is part of a series of history articles, which will appear each weekend, barring any major news stories. Next week’s article will focus on the 25th anniversary of STS-37, which launched —and saved—NASA’s Compton Gamma Ray Observatory.

Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

One Comment

One Ping

Pingback:Spacewalkers Ready for US EVA-37, Days Ahead of Expedition 48 Crew Return « AmericaSpace