Twenty-five years ago, tonight, fire and thunder rattled the marshy landscape of Florida and an artificial sunrise—for just a few minutes—created a new dawn. At 6:48 p.m. EST on 15 November 1990, Atlantis roared into orbit on the seventh classified shuttle mission for the Department of Defense. Aboard the orbiter for the projected four-day flight were Commander Dick Covey, Pilot Frank Culbertson, and Mission Specialists Carl Meade, Bob Springer, and Charles “Sam” Gemar, and STS-38 would deliver a secretive payload into space to support a gradually escalating international military presence in the Middle East, following the August 1990 invasion of Kuwait by the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein. For Carl Meade, it was the eve of his 40th birthday, but for all five astronauts it was culmination of months of frustrating delays and the pinnacle of five lifetimes spent dreaming about aviation.

As described in yesterday’s AmericaSpace history article, Atlantis’ launch was originally targeted for May 1990, but shifted to the mid-July timeframe as the busy shuttle manifest took shape in the first half of that year. However, a series of hydrogen leaks associated with the 17-inch-diameter (43 cm) disconnect hardware aboard her sister ship, Columbia, prompted fleetwide inspections and a similar problem was identified on Atlantis. As a consequence, STS-38 flew several months later than planned, carrying a payload which remains shrouded in mystery and rumor, even a quarter-century later.

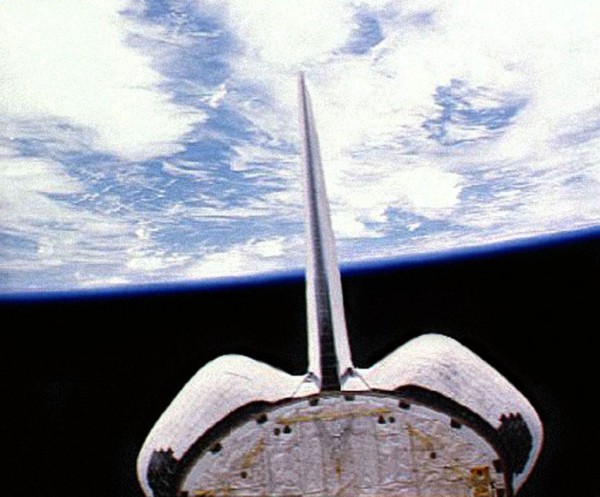

Its original published designation was “Air Force Program-658” (AFP-658), and initial speculation centered on the possibility that Covey’s crew deployed a Magnum Electronic Intelligence (ELINT) satellite—of similar design to the payload lofted by the astronauts of Shuttle Discovery on Mission 51C in January 1985—atop a Boeing-built Inertial Upper Stage (IUS) booster. However, many years after STS-38, on-orbit images of Atlantis’ vertical stabilizer revealed no trace of the donut-shaped Airborne Support Equipment (ASE) “tilt-table,” which was known to have accommodated all IUS-based cargoes in the payload bay. More recently, it became generally accepted that STS-38 deployed a member of the second-generation Satellite Data Systems (SDS-B) telecommunications relays, inserted into Geostationary Transfer Orbit (GTO). All told, it is believed that three SDS-Bs were launched by the fleet of reusable orbiters, on STS-28 in August 1989, aboard STS-38 and finally on the final Department of Defense shuttle mission, STS-53 in December 1992.

Almost a decade after Covey’s mission, in the spring of 1998, imagery and videotapes of an SDS-B under construction were released by the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), together with the identity of its prime contractor, Hughes. Physically, the satellite resembled the Syncom-4—also called “Leasat”—military communications satellites, operated by the U.S. Navy, which were deployed from the shuttle in a sideways, frisbee-like motion. The last Syncom-4 was carried aboard STS-32 in January 1990. It has been suggested that the SDS-Bs occupied a high-apogee and low-perigee orbit, ranging from as close as 300 miles (480 km) and as distant as 23,600 miles (38,000 km), and functioning at steeply inclinations which achieved apogee over the Northern Hemisphere. This enabled them to cover two-thirds of the globe, relay spy satellite data of the entire Soviet land mass, and cover the entire north polar region in support of U.S. Air Force communications. Such wide coverage was not possible to geostationary-orbiting satellites.

The SDS-B (possibly codenamed “Quasar”) featured a pair of 14.7-foot-diameter (4.5-meter) dish antennas and a third, smaller dish for Ku-band downlink. It is also believed to have carried the Heritage (Radiant Agate) infrared early-warning system for ballistic missile detection capability. Overall, the satellite measured 13.1 feet (4 meters) long and 9.8 feet (3 meters) wide in its stowed configuration, with a launch mass estimated at somewhere in the range of 5,000 pounds (2,300 kg) and 6,600 pounds (3,000 kg). Although it is unclear as to how they were deployed, some observers have assumed that they were “rolled” out of the payload bay, like a Frisbee, in a similar fashion to the Hughes-built Syncom-4 satellites. Others have noted that the solid-fueled rocket booster used for the SDS-B was an Orbus-21, physically identical to the motor later fitted to Intelsat 603 by spacewalking astronauts during STS-49 in May 1992. This has prompted alternative suggestions that the SDS-B was deployed “vertically” from a special cradle in the payload bay, in an orientation closer to that of Intelsat 603 than Syncom-4.

Irrespective of how SDS-B departed Atlantis, it is certain that the deployment was completed in the early hours of 16 November 1990, about seven hours into the STS-38 mission, after which the orbiter performed a separation burn to move to a safe distance in anticipation of the firing of the satellite’s motor. However, according to observer Ted Molczan, writing in February 2011, the delta-V of Atlantis’ burn was less than a tenth of what it should have been for a motor attached to a payload the size of an SDS-B. Moreover, he noted that the satellite itself lingered for some time in low-Earth orbit, rather than initiating its climb to operational altitude at the next available ascending node.

Then, in 1999, came the first mutterings that STS-38 might also have launched a second, more covert payload, known only as “Prowler.” Molczan explained that Prowler was deployed 22 hours after the primary payload. The shuttle’s crew then apparently performed an unusual maneuver, by lowering their orbit, rather than raising it. “It also happened to arrest the separation from the SDS,” Molczan wrote, “and initiate a very gradual overtaking, perhaps to create the impression of a rough station-keeping maneuver [by Atlantis] to keep Soviet attention focused on the SDS.” It would also appear that the SDS-B finally fired its Perigee Kick Motor (PKM) during a 16.5-hour period which overlapped the firing of Prowler’s own motor. Detection by the Soviet-operated signals intelligence station near Havana might have been circumvented, Molczan continued, by timing the deployment of Prowler very carefully to when Atlantis passed beyond the Cuban radar horizon.

As for Prowler itself, even today the fiction and the speculation greatly outweigh the facts and the evidence. Due to its brightness, a case has been advanced that it was a Hughes HS-376 spacecraft “bus”—very much like the cylindrical communications satellites launched on several shuttle missions in the early 1980s—with an attached Payload Assist Module (PAM-D) to boost it into geostationary orbit. Molczan suggested a total payload weight of around 9,900 pounds (4,500 kg), of which 2,860 pounds (1,300 kg) was the satellite itself and a further 4,600 pounds (2,100 kg) for the PAM-D, and argued that the ability of the shuttle to carry both it and the SDS-B was well within its performance envelope.

Clearly, STS-38 was a heavy mission, as highlighted by its orbital altitude, which did not venture much higher than about 155 miles (250 km). “You can read a lot into that,” Dick Covey admitted, years later, to NASA’s oral historian. “We didn’t go very high because we couldn’t go very high, which says we probably had a heavy payload. That was the thing that was really unique about the whole mission.” Of course, for much of the first decade after the conjectured launch of Prowler, its existence was unacknowledged. The presence of two spent rocket motors—codenamed “1990-097C” and “1990-097D” in a catalog of orbital objects—could be explained simply as representing the expended first and second stages of an IUS booster, without raising suspicion.

As to Prowler’s nature, labels such as “Geolocation Platform,” “Optically Stealthy,” and “Inspector” have been banded around over the years and the consensus seems to be that it was some kind of low-observable satellite, employed to rendezvous and secretly inspect other nations’ satellites in geostationary orbit, 22,000 miles (35,000 km) above Earth. At face value, the mission seemed impossible. Some observers doubted that it was even possible, in 1990, to conduct unmanned rendezvous in geostationary orbit, although such exercises had long since been routinely performed by the Soviets in low-Earth orbit between Progress cargo craft and the Salyut and Mir space stations. Others countered that geostationary altitudes provide a more benign environment for telerobotic operations and relative motion control and even wondered if Prowler might have performed radio frequency blocking; literally parking itself in front of a satellite’s antenna path to block its signals. Still others have gone further: that Prowler did attempt such blocking, albeit experimentally, on U.S. communications satellites, and several analysts have argued that it could have positioned itself within a foot (30 cm) of a target.

Whatever the reality, it is certain that the curtain does not stand to be lifted on STS-38 for many more years to come. Yet this quiet mission had one more surprise in store. Its landing was scheduled for 19 November 1990, after four days in space, but was routinely postponed by 24 hours, due to unacceptable crosswinds at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., which caused all three opportunities for that day to be scrubbed. Unfortunately, the weather in the Mojave Desert on the 20th showed no sign of improvement and, with on-board consumables until the 21st, NASA diverted Atlantis to the Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC). It would mark the first shuttle landing in Florida since Mission 51D in April 1985, which touched down in a crosswind and suffered seized brakes and a burst tire.

It was with some surprise that Covey received a call from Entry Flight Director Lee Briscoe—bypassing the Capcom—and asked him if he was happy to divert to Florida. Although it had been more than five years since a shuttle had made landfall on the East Coast, the answer was a no-brainer for Covey. He had flown so many simulated approaches to Florida that he was more than happy to do so. The landing would occur in the late afternoon and fellow astronaut Mike Coats, flying the Gulfstream Shuttle Training Aircraft (STA) on weather reconnaissance, was responsible for determining whether conditions were optimum to receive Atlantis.

“This is the fall of the year,” explained Covey in his NASA oral history, “and one of the things that they do in Florida during the fall is burn the underbrush in their pine forests; a very controlled type of burn, just to get everything down. They were doing that over on the west side of the [Banana] River in Florida and the winds were predominantly from the north-east … so they were blowing that smoke out over central Florida, toward Orlando.” Based upon this factor, Coats recommended that Covey should land on the south-eastern end of the SLF, on Runway 33. By the time Atlantis neared the time to fire her Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) engines for the irreversible de-orbit burn, the winds shifted. “The smoke was coming pretty much right across the southern half of the runway,” Covey recalled, “and the northern half was clear.”

Coats held off from advising a landing on the Runway 15 “end”—which would have required Covey to perform a left-hand maneuver during final approach—and the astronauts were advised that the smoky conditions might prove problematic. Added to this was the fact that it was near sunset on the Space Coast and the refractive effect caused the smoke to appear thicker. A little after 4:30 p.m. EST, as Atlantis came within minutes of touching down on Runway 33, the astronauts could see very little through their windows. That said, Covey and Culbertson had great confidence in the shuttle’s guidance capabilities and as the vehicle rolled out on final approach, they spotted the Precision Approach Position Indicator (PAPI) lights on the runway perimeter, barely visible through the smoke. These gave Covey the visual reference that he needed, but as Atlantis descended lower, passing into the smoke, he could see nothing but the lights; the runway itself was invisible to him. At length, the smoke cleared and there, right ahead, lay the runway.

“Frank lowered the landing gear and we landed,” he recounted, “and I think, technically, I get to log an instrument approach on that!” Touchdown came at 4:42 p.m. EST. Atlantis had flown through conditions of visibility which would ordinarily never have been sanctioned and for several years afterwards, Covey enjoyed reminding Coats of his recommendation, for the Runway 15 end of the SLF was totally clear of smoke by landing time! Two weeks later, an increasingly confident NASA announced its intent to resume “operational” shuttle landings in Florida and STS-43, launched in August 1991, became the first post-Challenger mission to be specifically directed to KSC as its primary End of Mission (EOM) site. By the close of the 30-year shuttle era in July 2011, no less than 78 landings—almost 60 percent of the total 133 successful shuttle touchdowns—had been completed in Florida.

This is part of a series of history articles, which will appear each weekend, barring any major news stories. Next week’s article will focus on the 30th anniversary of Mission 61B, an ambitious mission which laid the groundwork for the eventual construction of the International Space Station.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace