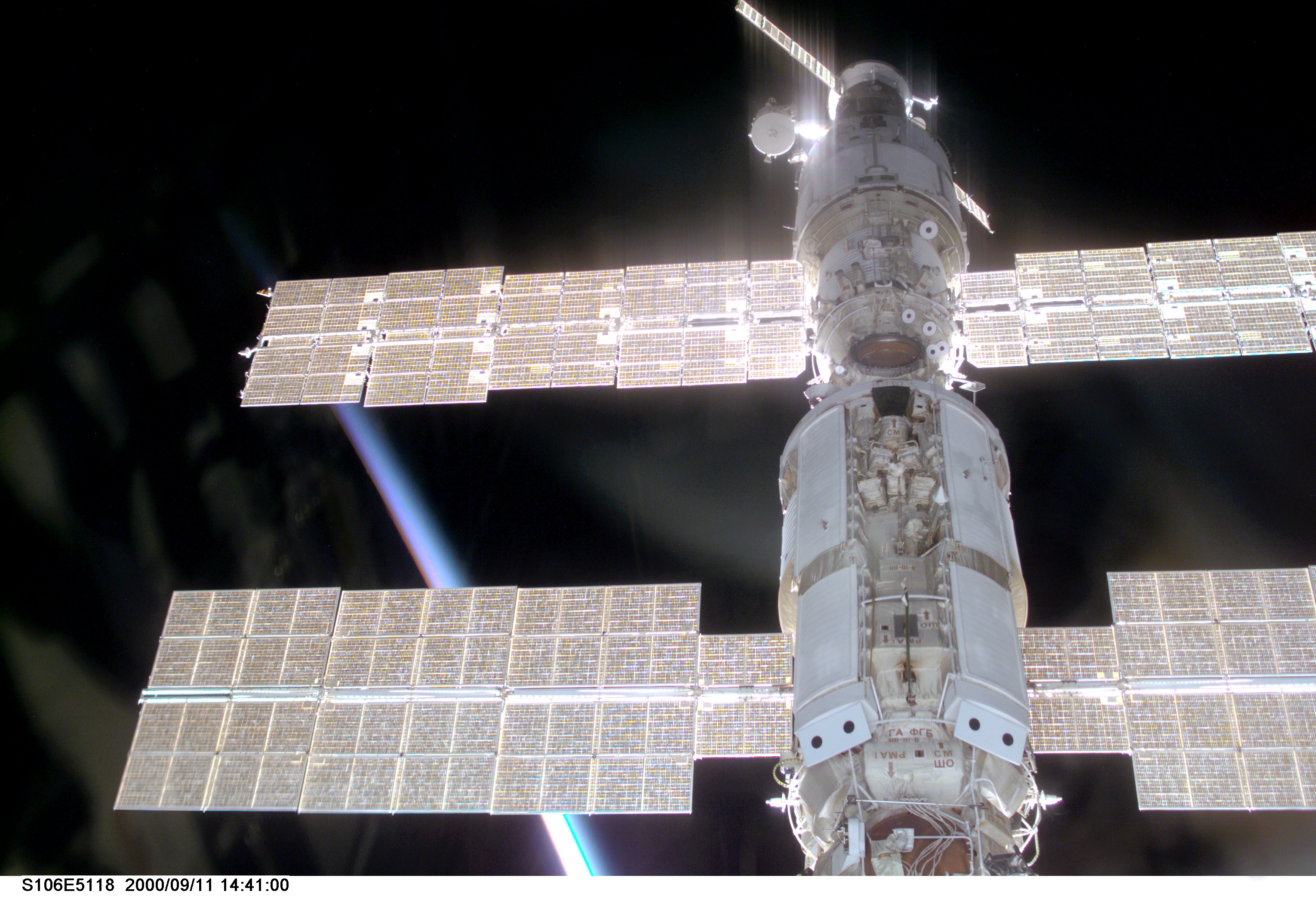

Fifteen years ago, this week, a space shuttle flight which very nearly didn’t happen, happened. In early 2000, the initial elements of the International Space Station (ISS)—which at that time comprised just two components, the U.S.-built Unity Node-1, with Pressurized Mating Adapters (PMAs) at both ends, and the Russian-built Zarya control module—had been in orbit for a little over a year, but further assembly had stalled, due to delays in launching Russia’s Zvezda service module. The latter would serve as the primary control center and living quarters for the station’s early long-duration crews, but had suffered from years of funding shortfalls and its launch had been pushed back yet further by a pair of Proton-K booster failures in July and October 1999. Not until all problems were resolved would Russia commit to launching Zvezda … and until that happened, no other ISS elements could fly. As 2000 dawned, that left the fledgling station in a critical condition.

Measuring 43 feet (13.1 meters) in length and based in design upon the core of the Mir space station, Zvezda was originally baselined to be launched, via Proton-K, from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan in the fall of 1998. After reaching orbit, it would be maneuvered over a period of two weeks toward a rendezvous and docking with the Zarya/PMA/Unity stack, effectively opening the floodgates for a sequence of shuttle missions to deliver the first elements of the Integrated Truss Structure (ITS), solar arrays and batteries, and several major pressurized modules, including the U.S. Destiny laboratory. However, significant further delays befell Zvezda and not until April 1999 was it ready to be rolled out from the manufacturing facility, ahead of delivery to Baikonur. Launch was provisionally scheduled for “no earlier than” 12 November, but was placed on indefinite hold when a pair of Proton-K boosters exploded, due to engine turbopump malfunctions.

Concurrently, NASA was readying Shuttle Atlantis for the STS-101 mission in March 2000—crewed by Commander Jim Halsell, Pilot Scott “Doc” Horowitz, and Mission Specialists Mary Ellen Weber, Jeff Williams, Ed Lu, and Russian cosmonauts Yuri Malenchenko and Boris Morukov—to deliver supplies and conduct much-needed repairs. Originally targeted to occur after Zvezda’s arrival, the delays meant that STS-101 would now arrive several months earlier than the service module. Of particularly worrisome note was the fact that by this point, only four of the Zarya module’s six batteries were in full working order after 14 months in orbit. Coupled with this was an ongoing solar maximum, which increased the atmospheric drag on the ISS and necessitated an urgent reboost of its altitude. With all of these tasks, it was recognized that STS-101 was too complex to support them all, and in early January 2000 the first mutterings reached the media that another mission, STS-106, was being considered as a short-notice insertion into the shuttle manifest. Both flights would utilize Atlantis, with STS-101 launching on 16 March, Zvezda set to depart Baikonur no sooner than 20 May and STS-106 rocketing aloft as early as 8 July.

However, Russia’s insistence upon flying at least three fully successful Proton-K missions before Zvezda—for which no backup module was available and which had not been insured, due to the ongoing economic situation—led to an announcement in early February that the service module would launch no sooner than 8-14 July. With STS-101’s pre-flight processing running four to six weeks behind schedule, making an April launch unavoidable, STS-106 would correspondingly be expect to fall back to August. In the midst of these deliberations, on 18 February NASA announced revised crew assignments for Atlantis’ two missions. Halsell, Horowitz, Weber, and Williams would remain aboard STS-101, but would be accompanied by future Expedition 2 crew members Yuri Usachev of Russia and U.S. astronauts Jim Voss and Susan Helms, whilst Lu, Malenchenko, and Morukov would move onto the new STS-106 roster. Joining them would be Commander Terry Wilcutt, Pilot Scott Altman, and Mission Specialists Rick Mastracchio and Dan Burbank.

As circumstances transpired, Russia managed to launch no fewer than seven Proton-Ks between 12 February and 4 July 2000, all successfully, and all of which delivered multiple communications satellites into Geostationary Transfer Orbit (GTO) at an altitude of 22,300 miles (35,700 km). By the end of June, a formal General Designers Review in Korolev, Russia, produced a unanimous decision to press ahead with an opening launch attempt on 12 July and Zvezda speared perfectly into orbit at 11:56 a.m. local time (1:56 a.m. EDT). Two weeks later, it successfully docked at the aft port of Zarya. “This mission truly represents the beginning of a long and fruitful adventure for NASA and the international space community,” said then-NASA Administrator Dan Goldin. “The space program has led to thousands of new technologies, new breakthroughs in medical research, new medicines, new discoveries that have literally changed the lives of people all over the world. I can’t wait to get started.”

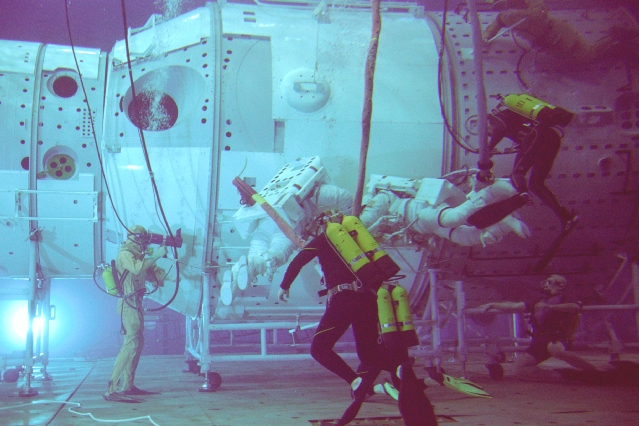

The seven astronauts and cosmonauts who would form the crew of the 99th Space Shuttle mission had already gotten started and, by July, were feverishly laboring toward a revised launch target of 8 September. Their abbreviated half-year training template was significantly at odds with normal operational procedures. “It’s kind of a blessing it’s only six months, instead of 12,” Wilcutt joked in a pre-flight interview. “When we first got assigned, we front-loaded a lot of the training to get us up to speed as quickly as possible. We worked weekends and obviously, not only are we, the crew, working weekends, but our training team is working weekends, too. After we got a certain level of expertise in what the mission would require, got us back up-to-date and current in shuttle systems, then our training slacked off to more of a normal training flow.”

By Wilcutt’s admission, it was far from straightforward. “Part of my responsibility as Commander is not only the accomplishment of the mission, but the welfare of your people,” he explained. “My crewmembers have families and children, so having them work six days a week, we needed to pour on the training at first, so that we could slack off and give them a little more time with their folks later in the flow.” He paid specific tribute to the Space Shuttle Program (SSP) for having reached a level of maturity to be able to insert an entirely new flight—designated “ISS-2A.2b,” the second half (2b) of the second American assembly mission (ISS-2A) to the International Space Station—into the manifest at six months, as well as extending praise to the Astronaut Office for its ability to rise to every challenge.

For Wilcutt’s colleagues, three of whom had flown before and three others who had yet to savor the weightlessness of space, the feelings were the same. Dan Burbank, making his first flight, had previously worked with the STS-101 crew on their Zvezda training, whilst veteran cosmonaut Yuri Malenchenko—who had previously spent four months aboard Mir in July-November 1994—had been specifically assigned to the mission to lead the early outfitting of the service module. He was joined by Morukov, “because there are a number of different tasks on the Russian segment and our Russian experts wanted to have two Russian crewmembers.” Despite their wealth of experience, however, there were challenges in joining a new crew. “It takes a while to get a crew to work together as a crew,” explained Lu, shortly before the STS-106 launch. “You can’t be sort of seven individuals, off doing your own thing. In the end, it has worked out and we’re working together as well as the old 101 crew did back in February.”

One key issue raised by several of the astronauts was time-management, “figuring out how to make everything fit into the limited time that we have before launch,” according to Lu. “I think we’ll do just fine, and I think we’ll go into the flight ready and not overly beat up and tired from having stayed up all night for six months!” Scott Altman’s previous mission had been a long-duration Spacelab flight, for which he had enjoyed a year-long training template, and he noted that simply fitting the STS-106 preparations into six months was tough. “The days get long; you get very busy with the training,” he said, “but I think what we’re doing is reviewing our training and coming to the point where we know exactly what’s required and trying to cut that down to what we need to put all the crews through to get them ready to fly in space.” Burbank added that normal circumstances called for shuttle crews to be assembled a year to 18 months in advance of flight, in order to build the friendship and the camaraderie, “and I think we’ve more than surprised everybody, including ourselves” to have achieved it in just six months.

Of course, each of the astronauts also praised the efforts of their training teams, who also stepped up to the plate in anticipation of this record-time shuttle flight. “We all know the space station is a huge program,” said Mastracchio, who served as the flight engineer during the ascent and re-entry portions of the mission. “There’s over a dozen countries involved and there’s a lot of hardware and software involved in the building process. I think STS-106 is a great example of how NASA can successfully recover from these unplanned events and continue the program to a success.”

As Wilcutt and his men pressed on with their training, STS-101 eventually launched on 19 May and conducted the long-awaited repairs to Zarya, before Atlantis returned to a smooth touchdown on the Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) on 29 May. The vehicle was immediately transferred to the Orbiter Processing Facility (OPF) for immediate post-flight attention and spent almost 10 weeks undergoing preparations for STS-106. Finally, at 10:40 a.m. EDT on 7 August, she was rolled into the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) for stacking onto her External Tank (ET) and twin Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) in High Bay 1. Six days later, the complete STS-106 stack was transferred to Pad 39B, by which time the Spacehab Double Module—a pressurized element containing much of the cargo bound for the ISS—had also arrived, ready for installation into her cavernous payload bay. Later that same month, Space Shuttle Program managers keenly watched the progress of Hurricane Debby, which originated as a tropical wave off the Lesser Antilles, before evolving into a tropical storm and later strengthening into a hurricane by the third week in August, as they pushed on with the effort to load hypergolic propellants aboard Atlantis and install the connecting tunnel between the Spacehab and the middeck.

A few days before the planned 8 September launch, in stormy conditions with an elevated risk of lightning and rain, the seven astronauts and cosmonauts flew from Ellington Field in Houston, Texas, to KSC in their fleet of T-38 Talon training jets. “You have no idea, unless you’re looking at this storm, how great it is to be here on the ground at KSC,” exulted Wilcutt. “What a trip!” Air Force meteorologists predicted a 60 percent likelihood of acceptable conditions at T-0, but on the evening of 5 September Pad 39B’s Lightning Protection System suffered a direct strike. Possible damage was also incurred with the Tactical Air Navigation (TACAN) hardware at the SLF. Conditions on 9 September improved to 70 percent favorable, with a further improvement to 80-percent acceptable by the 10th, although NASA stressed that it would only make two back-to-back attempts, before standing down to top up Atlantis’ cryogenic consumables.

However, with Zvezda now in orbit and safely docked to the ISS, the excitement was palpable, as a sequence of intricately planned shuttle and Soyuz missions lined up to commence the building of the space station and its permanent habitation. “The floodgates have been opened,” said veteran flight director Wayne Hale, “and we’re in high gear.” STS-106’s brief launch window of less than four minutes had been tightly refined to a period extending from 8:45:47 a.m. EDT and 8:49:44 a.m. EDT. Unfortunately, as Launch Day dawned, there was great pessimism, with off-shore rain showers and heavy cloud ominously approaching KSC, which threatened to violate Launch Commit Criteria (LCC).

Nonetheless, the loading of the ET with cryogenic hydrogen and oxygen got underway and the tank was full by 3 a.m. Shortly thereafter, the astronauts were awakened, breakfasted at 3:50 a.m., completed weather briefings and suited-up for launch. At 4:56 a.m., they departed the Operations & Checkout (O&C) Building and boarded the Astrovan for the ride to Pad 39B and Atlantis. Wilcutt, Altman, Lu and Mastracchio were seated on the flight deck, with Burbank, Malenchenko and Morukov stationed downstairs on the darkened middeck. The shuttle’s side hatch was closed and locked at 6:40 a.m.

Against many odds, the countdown emerged from its final, pre-programmed hold at T-9 minutes and ticked steadily down to the opening of the launch window at 8:45:47 a.m. With 31 seconds to go, Autosequence Start transferred primary critical command of all vehicle functions from the Ground Launch Sequencer (GLS) over to Atlantis’ suite of on-board General Purpose Computer (GPCs). At 15 seconds, sound-suppressing water began to flood across the base of Pad 39B, leading up to the “Go for Main Engine Start” at T-10 seconds. “ … Nine, eight … we have a Go for Main Engine Start … ,” reported launch commentator Bruce Buckingham, as the engines rumbed to life, their dancing Mach diamonds piercing the murk, “ … four, three, two, one … we have booster ignition and liftoff of the Space Shuttle Atlantis, opening the door to a permanent human presence in space.”

From his seat on the flight deck, Terry Wilcutt could be heard making the familiar “Roll Program” call, 10 seconds after liftoff, to which the Capcom in the Mission Control Center (MCC) at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston responded crisply: “And this is Houston, Roger Roll!” As Atlantis rose for the second time in 2000, she carried the dreams of hundreds of thousands of people, worldwide, to get the stalled construction of the space station back on track. With another mission scheduled for October, before the arrival of Expedition 1 in early November, STS-106 promised to be a busy 12 days.

The second part of this article will appear tomorrow.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

2 Comments

2 Pings & Trackbacks

Pingback:Cosmic Ballet: Remembering Atlantis on 30th Anniversary of Maiden Flight (Part 4) « AmericaSpace

Pingback:‘This True American Icon’: Remembering Atlantis on 30th Anniversary of Maiden Flight (Part 5) « AmericaSpace