More than four decades ago, humanity first made landfall on the Moon and Apollo 11 Commander Neil Armstrong and Lunar Module Pilot (LMP) Buzz Aldrin left their footprints on the dusty regolith of the Sea of Tranquility. Over the span of those decades, we have grown familiar with the sights and sounds and experiences of six pairs of intrepid explorers who touched down in areas as diverse as the flat “seas” (or mare) of Tranquility and the Ocean of Storms, the hummocky foothills of Fra Mauro and the mountainous regions of Hadley-Apennine, the Descartes highland plains, and the tiny valley of Taurus-Littrow. To commemorate the anniversary of Apollo 11—which reached the Moon 46 years ago, this week—AmericaSpace will focus not upon the well-documented experiences of the astronauts on the lunar surface, but upon one of the less well-known experiences of life on an alien world: how they managed to rest and sleep aboard the cramped confines of their Lunar Module (LM), surrounded by the ethereal stillness, the silence of ages, and the realization that as they slumbered they were the only living beings on this lifeless, airless world.

Right from the start, it was clear that each of the Apollo landing crews would be required to spend at least one Earth “night” on the lunar surface. In the case of Armstrong and Aldrin—whose triumphant flight represented the so-called “G” mission in a series of seven core steps to plant American bootprints on the Moon—it was anticipated that about 22 hours would elapse between the touchdown of their Lunar Module (LM) Eagle and their liftoff to rejoin their Apollo 11 crewmate Mike Collins aboard the Command and Service Module (CSM) Columbia in lunar orbit. Subsequent flights were expected to spend yet longer on the Moon, with the “H”-series missions of Apollos 12, 13, 14, and 15 scheduled to remain for about 33 hours and feature a pair of EVAs and, finally, the “J”-series missions of Apollos 16, 17, 18, and 19 spending approximately three days on the surface, benefiting from a battery-powered Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV) and performing a trio of EVAs. However, as described in an earlier AmericaSpace history article, in September 1970 Apollos 18 and 19 succumbed to budget cuts and Apollo 15 was advanced from the last H-series mission to the vanguard of the expanded J-series.

With this in mind, each landing crew would need to take time to sleep aboard the confined ascent stage of the LM, whose dimensions and angular interior were described by Aldrin in his 1989 memoir Men From Earth as akin to the cab of a diesel locomotive. “Weight restrictions prevented the use of paneling, so all the wiring bundles and plumbing were exposed,” he recalled. “Everywhere I looked there were rivets and circuit breakers. The hull had been sprayed with a dull gray fire-resistant coating. Some people had said the first Moon landing would be the culmination of the Industrial Revolution; well, the Lunar Module certainly looked industrial enough to prove it.”

Early plans called for the landing crews to sleep shortly after touching down, with Armstrong and Aldrin originally timelined to complete two hours of post-landing checks, then eat for 35 minutes, rest for four hours, eat breakfast, then don their suits to become the first human beings ever to set foot on another world. “Whoever signed off on that plan didn’t know much psychology—or physiology, for that matter,” Aldrin wrote. “We’d just landed on the Moon and there was a lot of adrenaline still zinging through our bodies. Telling us to sleep before the EVA was like telling kids on Christmas morning they had to stay in bed until noon.” In the weeks before launch, Armstrong and the mission planners discussed the possibility of skipping this brief sleep period and proceeding directly into what was termed “EVA Prep.” Not long after achieving the first piloted landing on the Moon, Armstrong formally requested to cancel the short sleep period and elected to press directly into EVA Prep timeline. His request was accepted.

Several hours later, after re-entering the cabin and removing and disposing of their Portable Life Support System (PLSS) backpacks, sturdy lunar overshoes, and unneeded gear, Armstrong and Aldrin were finally presented with the opportunity for a bite to eat and time to rest. They snacked on cocktail sausages and fruit punch, then Aldrin stretched himself out on the deck beneath the instrument panel and Armstrong propped himself across the 2.5-foot-diameter (0.7-meter) drum-like ascent engine cover, with his legs elevated by means of a makeshift sling, fashioned from a waist tether, and with his boots wedged underneath the Display and Keyboard Unit (DSKY) of the main control console. He rested his head on a flat shelf, behind the ascent engine cover. Years later, James Hansen noted in First Man—his authoritative biography of Armstrong—that the night was a far from pleasant experience. It was also noisy and a loud glycol water pump seriously interfered with their sleep.

Neither man could stretch out on the floor of the LM, but were obliged to adopt a position which was little more than fetal, and the lack of comfort was exacerbated by the fact that both men were still clad in their bulky space suits, including helmets and gloves, in order to protect their lungs from the lunar dust which they had tracked inside. “The filtered oxygen from the LM’s environmental control system,” wrote Hansen, “was significantly cleaner than the air circulating in the cabin.” Moreover, they hoped that it would produce a quieter night’s sleep, fully buttoned up inside their suits.

“With the windows shaded, the LM grew cold,” Aldrin wrote of the temperatures, which typically hovered around 16 degrees Celsius (61-62 degrees Fahrenheit). Armstrong agreed. “The temperature got quite brisk in the cockpit,” he told Hansen. Despite the shades having been drawn, it was still not truly dark, and Armstrong recounted in his post-flight Technical Debrief that they served in a fashion not dissimilar to photographic negatives, allowing a lot of light from the Sun-drenched lunar surface to continue to enter the cabin. At the same time, many of the Caution & Warning (C&W) lights and illuminated switches could not be dimmed and the Alignment Optical Telescope (AOT)—situated on Armstrong’s side of the cabin and used during the rendezvous with the CSM—was pointed directly at the bright disk of Earth, which provided a constant light source, despite the astronauts tying a makeshift cover over it. A noisy glycol pump exacerbated the problem. “This was a never-ending battle to obtain just a minimum level of sleeping conditions, and we never did,” Armstrong summarized in the post-flight debriefing.

Five more pairs of astronauts also spent at least one night’s sleep on the Moon after the departure of Armstrong and Aldrin, none of whom experienced the same difficulties with regard to light intrusion through the window shades. At the post-flight debriefing, Mike Collins noted that the Apollo 12 crew planned to remove their suits in order to sleep, but as circumstances transpired this did not happen. “I don’t feel that having the suit in one-sixth G is that much of a bother,” Aldrin recalled of his experience sleeping fully-suited. “It’s fairly comfortable. You have your own little snug sleeping bag, unless you have some pressure point somewhere. Your head in the helmet—which has a pad at the back of the head—assumes a very comfortable position. Even out of the helmet, you don’t have to worry about what you’re leaning against. Your head doesn’t weigh that much and will very comfortably pick just about any position.”

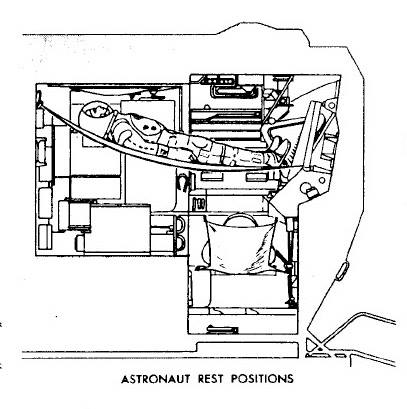

Four months later, in November 1969, Apollo 12 Commander Charles “Pete” Conrad and LMP Al Bean embarked on the first H-series mission, spending 33 hours on the surface and performing two EVAs. In his own inimitable style, Conrad treated the request to sleep before their first Moonwalk with some scorn—“the third and fourth in the history of the species to set foot on this thing … and you expect us to sit down for a smoke break?”—and they too ventured outside onto the surface, ahead of schedule. Returning to the cabin several hours later, they kept their suits on, but removed their helmets, boots, and gloves and bedded down in a pair of beta-cloth hammocks. It was the first time these hammocks had been used, and they were typically strung across the cabin, with the Commander positioned fore-to-aft, and the LMP beneath him, from port-to-starboard. Equipped with blankets, hammock insulators, and Velcro attachment pads, these enabled a greater measure of comfort for the slumbers of successive Apollo landing crews.

“The hammocks were always there, as far as I know,” Bean later explained to Eric Jones of the Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. “We always were going to have them. There wasn’t any last-minute thought, ‘Well, hey, we gotta give you somewhere to sleep.’ I think we always knew we were having hammocks.” After rigging up the hammocks—with Conrad’s closest to the LM ceiling—the Commander moved to the raised aft section of the cabin, to enable Bean to get into his makeshift bed for the night.

Sleeping in their suits, Conrad admitted, as quoted by his wife, Nancy, in her biography, Rocketman, was about as snug as sleeping in football pads, and he caught himself on several occasions gazing through the triangular windows of the LM Intrepid at the bright lunar terrain outside. As with the experience of Armstrong and Aldrin, however, their sleep was far from fitful. Cooling water had somehow gotten into one of Conrad’s boots and the right leg of his suit had been poorly adjusted before launch, making it too short, and this created the effect of pulling on his shoulder. He woke Bean at one stage and they untied and retied cords around the leg of the suit. Yet the two men barely slept; Bean later regretted not taking a sleeping pill, and they dozed for no more than a few hours apiece. Conrad found the soft strains of Patsy Cline from a small cassette tape recorder was the best sleeping aid.

Fifteen months later, in February 1971, with Apollo 13 having been aborted during its journey to the Moon, the landing crew of Apollo 14 were the next pair of humans to spend a night in the uncomfortable LM, surrounded by the ethereal stillness of Fra Mauro foothills. After concluding the first of their two EVAs, Commander Al Shepard and LMP Ed Mitchell strung their hammocks in a crisscross formation across the tiny cabin and struggled to sleep. First, they stowed their boots on the left side of the cabin, removed their helmets—placing one on the floor and the other upon the ascent engine cover—then unrolled and rigged up their hammocks. “Remember, still being in the suits, we had our air and our water still going through the suits,” Mitchell told Eric Jones of the Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. “And so, in rigging your hammock, you had to make sure you rigged it so that, when you got into it, your umbilicals had a free route to the [Environmental Control System] stations. If you got tangled up and on the wrong side of it, you were in deep yogurt. It was very carefully choreographed, to get everything in the right place at the right time.”

Neither man opted to use earplugs; in Michell’s words, they wanted to be able to hear every sound. “But sleep was almost impossible,” wrote Shepard’s biographer, Neal Thompson, in Light This Candle. “Shepard felt like he had no place to rest his head. Air hissed from the air conditioner. Mitchell kept raising the window shades to look outside.” Their LM Antares had touched down at the slight angle, of about 8 degrees, and every move they made generated the subconscious feeling that their ship was about to tip over. On one occasion, Shepard scrambled out of his hammock and promptly fell onto his crewmate. After his return to Earth, Mitchell pointed out that the slight angle probably would have been less noticeable when standing upright, but when trying to sleep it was obvious. “If we had to land at the limit of the LM envelope—about 10-15 degrees—I think the guys would find it almost intolerable to work in the LM and sleep in it at that angle,” he recalled in his post-flight technical debriefing.

At other times, both men were awakened from their light slumber by the mild groaning of Antares’ systems, the rustling of its paper-thin walls, and the gentle hiss of its life-sustaining machinery. One conversation between them is particularly comical:

“Ed? Did you hear that?” Shepard whispered.

“Hell, yes, I heard that.”

“What the hell was that?”

“I don’t know.”

A few seconds passed. Then:

“Ed?”

“What?”

“Why the hell are we whispering?”

If the first three lunar landing crews had gone EVA before bedding down for their first sleep period, that protocol changed with the experience of Commander Dave Scott and LMP Jim Irwin on Apollo 15 in July-August 1971. As the first “J”-series mission, they were tasked to spend about 66 hours on the surface and had to shift their paradigm from simply visiting the Moon to actually living there. They would sleep before the first of their three EVAs, but it was not going to be easy. “Our schedule … had been designed originally to include a sleep period before we started exploring,” Scott wrote in his memoir, Two Sides of the Moon. “I had realized early on in our training the importance of maintaining our circadian rhythms in order to be able to perform at peak during our three days on the Moon. And, with so much adrenaline pumping, there was no way we could just pull down the blinds shortly after landing and simply go to sleep.”

On this mission, Scott performed the Apollo Program’s first—and only—Stand-Up EVA (SEVA), clambering onto the ascent engine cover of the LM Falcon and poking his head out of the overhead rendezvous hatch to conduct a 360-degree panoramic photographic reconnaissance of the landing site. After this activity had been completed, he and Irwin settled down for a meal of cold tomato soup, then became the first Apollo crew to remove their suits and strip down to their water-cooled underwear in order to sleep; the sheer length of their time on the Moon made this decision, in Scott’s mind, a critical one.

“I think it was biting the bullet,” said Apollo 14’s Ed Mitchell of the decision to remove suits entirely for sleep periods on the final three landing missions, “and because they did three EVAs, there was a crew exhaustion factor. Unless they got some relief from that suit and tried to get a decent amount of sleep and get to take a crap and do all the things you need to do, their performance would be degraded in that length of time. They figured that, for two EVAs, we could get by with it and it wasn’t worth risking the damage or degradation of the suit integrity and so forth, but you just couldn’t use that logic when you got to the J-missions and three EVAs.”

“That first night, we pulled down the blinds of the LM’s two small triangular windows to block out the intense sunlight,” Dave Scott wrote in Two Sides of the Moon, “and strung up our hammocks across the cramped cabin.” During training in the LM simulator at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC), he and Irwin had experienced a “lousy” night’s sleep, but on the Moon—and aided by the lightness of one-sixth terrestrial gravity—the hammocks felt much softer. “With the background mechanical symphony of the LM’s pumps and fans,” wrote Scott, “we popped in earplugs and were pretty comfortable as we settled down to sleep up there on the Moon that first night.” In his own autobiography, To Rule the Night, Irwin remembered that Scott arranged his hammock fore-aft, “and I was athwart ship, with my hammock slung below his.” His hammock bowed out a little, and his feet dangled off the end. Yet despite Irwin’s admission that it was a noisy night’s sleep, with the pumps and fans running, and his comparison of the LM to a boiler room, he acquiesced that it was comfortable. “Those hammocks felt like water beds and we were light as a feather,” he wrote. “That first night’s sleep was the best I had the three nights I was there.”

Understandably so, for the following two nights’ sleep would be done after the astronauts had tracked lunar dust—and its pervasive, gunpowder-like aroma—into the cabin. They firstly stepped into large cloth bags to remove their suits, then stepped out of the bags and sealed them up until the following morning. The filthy suits were then stowed at the back of the tiny cabin, with the gloves in place, to protect the seals from any risk of abrasive damage. By Irwin’s admission, their conversation during the night was limited. A devout Catholic, Irwin prayed each morning and evening, but both men realized the importance to get to sleep as quickly as possible, to ensure that they were adequately rested for the EVAs. “And frankly, we both snore, and I guess I snore louder than Dave,” he wrote in To Rule the Night, “so there’s a contest: each of us wants to drop off before the other starts snoring!”

The next J-mission, Apollo 16 in April 1972, featured a sleep period for Commander John Young and LMP Charlie Duke, ahead of the first of its three planned EVAs. “Even though we really wanted to get right out there, discretion was the better part of valor,” Young wrote in his autobiography, Forever Young, “and we were okay with it when Houston told us they wanted us to take a sleep period.” The two men stacked their suits and helmets on the ascent engine cover and, after rigging up their hammocks, bedded down for their first night’s sleep on an alien world. “Both of us somehow managed to sleep soundly—better, apparently, than any LM crew had to date,” Young wrote. “Charlie used a tablet of Seconal to help him sleep, and it worked fine. I slept like a brick.”

Eight months passed before a final pair of humans, Apollo 17 Commander Gene Cernan and LMP Jack Schmitt, landed in the tiny valley of Taurus-Littrow in December 1972. Like the two previous J-series missions, they embarked on three EVAs, betwixt each they removed their suits, draped them over the ascent engine cover of the LM Challenger, and attempted to sleep in the hammocks. “My feet were against an instrument panel and I took care not to kick any switches,” Cernan wrote in his autobiography, The Last Man on the Moon, “while my face looked up the tunnel and the suits poked me in the back. Damn, this thing was small.” Wide awake, Cernan found himself listening to the soft hum of the environmental control system, an occasional sneeze from Schmitt—courtesy of the ubiquitous lunar dust—from the hammock below and every so often he pulled back a window shade to reveal the lunar terrain, seemingly bleached almost white by the unfiltered sunlight. “There was an eerie stillness outside,” Cernan wrote, years later. “No hushed breeze or patter of raindrops, no crickets or frogs, not even any air. Every hour that I stayed on the Moon, the sense of absolute nothingness grew.”

“One-sixth gravity is a very pleasant sleeping environment with just enough pressure on your back in those hammocks to feel like you’re on something but not enough to ever get uncomfortable,” Schmitt told the Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. “I slept but my impression was that I only needed about five hours sleep to feel rested whereas ordinarily on Earth at that time I usually felt that I could use seven. But I think that’s related mainly to the lower gravity environment. You just don’t get physically as fatigued as you would on Earth.”

At times Cernan was struck by the irony of it: just outside that hatch was a whole Moon, waiting to be explored, and here he was, loafing around in his liquid-cooled underwear. With the departure of Cernan and Schmitt, no more lunar explorers would follow in their footsteps for the remainder of the 20th century and, even today, at the midpoint of the second decade of the 21st century, it is difficult to imagine when astronauts will again experience the ethereal stillness, absolute silence, and doubtless unnerving sensation of being the only living beings to sleep on this surface of this otherwise lifeless world.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Fun piece.

Great, interesting article – thanks for posting!

well researched and well written. A joy to read this, Mr. Evans!

Very interesting and long overdue article. Thank you for it.

I find it strange that eye covers weren’t used to filter out stray light from the windows. Another curious item in my mind–if I understand correctly–is the idea that the gloves and helmets could be removed but the suit couldn’t be–in the G and H missions. What was the point then, maintenance of suit integrity, as Mitchell had said?

Such a great question that I never considered and yet after reading it, it seems such an obvious question to ask.

Mr Evans I am glad you asked the question.

Great article.

After spending much time in the LM cabins during assembly and testing, I can easily picture the interior as described in this piece.

Funny, tho, when in there I never thought about how the guys would sleep — certainly doesn’t sound like desirable situation.

Great piece!

A fitting and importance piece in the complete understanding of the entire Apollo missions. I wonder if there are additional interior photos other than the very few published? Thanks, as always, Ben for providing your readers with interesting information.

“Some people had said the first Moon landing would be the culmination of the Industrial Revolution; well, the Lunar Module certainly looked industrial enough to prove it.”

Great quote.

90% of what got us to the moon was just plumbing and tankage, after all.