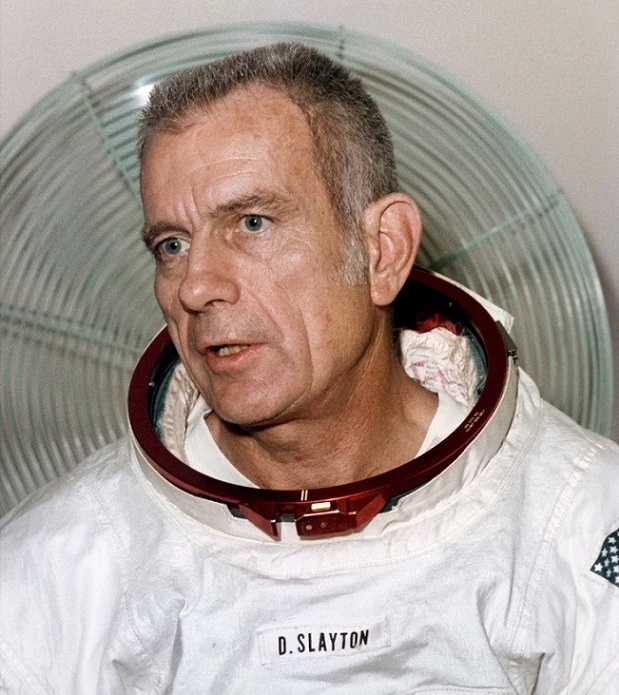

More than half a century ago, he was selected as one of America’s first seven Mercury astronauts. Almost four decades ago, after being controversially grounded by a suspected heart murmur, he finally rose from Earth on his first and only space mission. A little over two decades ago, he lost his life’s last battle, succumbing to a brain tumor, aged just 69. Now, in 2014—the year in which Donald “Deke” Slayton would have turned 90—he will be fittingly honored as Orbital Sciences Corp. launches its third dedicated Cygnus cargo mission (ORB-3) toward the International Space Station (ISS). When “Spaceship Deke Slayton” rockets into orbit tonight (Monday, 27 October), it will pay tribute to a guiding light in America’s early human space program, a key player in President John F. Kennedy’s drive to plant bootprints on the Moon, and a man who overcame many obstacles and never lost sight of his own dream to see the Earth from orbit.

Almost universally known as “Deke”—a nickname he earned as a test pilot at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., which was drawn from his initials—Donald Kent Slayton came from the small town of Sparta, Wis., where he was born on 1 March 1924. From his earliest childhood until the very end of his life, Slayton was an adventurer; as a four-year-old child, whenever allowed outside into the front yard, he was tethered to a tree by his mother at playtimes. It was not as a punishment or a cruelty, but out of her sheer terror at the amount of traffic which hurtled past the family’s dairy farm in small-town Wisconsin. “Eventually,” Slayton wrote, “I convinced my mother that I wasn’t going to go running into the road and I was set free. But I can make the case that ever since I was young I have wanted to explore … and people have tried to stop me.”

In many ways, Slayton’s upbringing on the family farm was the making of him. The work was hard, but rewarding, and it taught him the skills of business, entrepreneurship, book-keeping, and even the fundamentals of veterinary science. It was, he said, a good place to be raised and years later he would write, only partly in jest, that “compulsory farm rearing” would be an excellent experiment in building character. One of the downsides came in 1929 when the boy was helping his father to clear hay from a horse-drawn mower … and cleanly sheared off the ring finger of his left hand! “I was luckier than hell,” Slayton wrote in his autobiography Deke, co-authored with Michael Cassutt, “because I could have lost all of them. It didn’t hurt, but of course, my dad was pretty upset about it.” Physically, it hardly affected Slayton, and when he took up boxing in his teens he found that he could hit just as hard with his left fist as with his right. However, for many years, he was convinced that his missing finger was the first thing that anybody noticed about him.

Another interest to which Slayton was drawn in his teens was aviation, although by his own admission he had always feared warfare as a child. Nevertheless, four months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, in April 1942, he signed up with the U.S. Army Air Corps and underwent initial instruction in San Antonio, Texas, before moving to Vernon for flight training. His missing ring finger almost eliminated him from selection by the military, “but they checked the regulations and discovered that the ring finger on your left hand was the only finger you could have missing on either hand and be qualified as a pilot. Your ring finger, they decided, is the most useless finger on your hand!” Doubtless, many divorcees would be inclined to agree. …

Soaring through the skies in the Stearman biplane and the single-winged Fairchild PT-19 and North American Aviation’s AT-6 Texan, Slayton found a natural affinity for flying. Within a short time, he was assigned to advanced multi-engine training and in late 1943 was designated a combat-ready pilot for the B-25 Mitchell bomber. It was at this stage that he saw action for the first time, attached to the 340th Bombardment Group, initially in North Africa and later in the bombed-out Italian city of Naples.

“There’s a lot of just pure horseshit luck in flying,” Slayton later wrote in his typically straightforward manner, and his experience flying bombers over Italy and the Balkans was certainly demonstrative of this. On more occasions than he could count, he nursed B-25s back to base with blown tires and missing hydraulics or riddled with hundreds of holes of anti-aircraft gunfire. By the end of his time in Europe, Slayton had flown 56 combat missions, and after a short spell back in the United States he was assigned in April 1945 to the 319th Bombardment Group on the island of Okinawa. His seven combat missions over Japan were, in his own words, quite different from those over Italy and the Balkans, and by early August he was flying the A-26 Invader bomber, strafing coastal towns in readiness for a massive amphibious invasion of Japan—the planned, but never-realized “Operation Downfall”—by U.S. and Allied troops. When Slayton flew a combat mission on 12 August 1945, he did not know until after his return to base that the World War II was over. A few days earlier, two “big bombs” had been dropped on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki … and Slayton’s combat career was over.

After a year as a B-25 instructor, he left military service in November 1946 and enrolled at the University of Minnesota to study aeronautical engineering. Whilst there, he maintained his proficiency with the Air Force Reserve—the Army Air Corps having become a separate branch of the military services in 1947—and later joined the Minnesota Air National Guard, flying P-51 Mustang fighters. Two years later, in 1949, Slayton graduated in aeronautical engineering and was hired by Boeing to work on its new B-52 Stratofortress bomber. When the Korean War broke out in 1950, however, he was drawn back to the cockpit and active service. A rude awakening came when he tried to secure readmission into the Air Force: Since he had not applied for inactive reserve status within the required six months of leaving the Minnesota Air National Guard, he was officially now a civilian … and had to resume his career from scratch. Luckily, a former squadron commander managed to secure him a place as the Guard’s maintenance officer.

Two incidents of note occurred whilst there. The first was an immense storm which damaged perhaps 90 percent of the aircraft in his care … and the second was his sighting of an unidentified flying object whilst wringing out a newly-repaired P-51. It looked like a kite at first, but as Slayton drew closer he became convinced it was more likely a high-altitude weather balloon … until, that is, he approached it from a slightly different angle and it took the form of a disk on edge. It seemed to climb at a 45-degree angle away from him and then disappear. Slayton did not report the incident for a couple of days, then happened to mention it in conversation, only to be hauled before an Intelligence panel to make a formal statement.

The official position was that a local company had been testing a weather balloon and that, in addition to Slayton’s sighting, it had been tracked by a light aircraft and two ground-based observers with a theodolite. The only point of confusion was that its velocity was clocked at more than 3,700 mph (6,000 km/h)! “I don’t automatically presume that it came from Alpha Centauri,” Slayton wrote, “just because I can’t identify it. It’s still an open question to me.” Years later, though, he would wonder if his sighting ended up in the pages of the Air Force’s official UFO investigation, Project Blue Book.

Slayton’s desire to participate in the Korean conflict ultimately came to nothing, and he served three years in Germany as a maintenance inspector and squadron maintenance officer, securing his first experience in jet fighters. Then, in June 1955, he entered test pilot school at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., and qualified six months later. By his own admission, test flying in the mid-1950s was hugely risky and the pilots did not know the performance of their aircraft until they got back on the ground and examined the data. “Today they do everything real-time with telemetry and computers,” he wrote. “You do a test point and you can do analysis on it and say, obviously we’re going to the next one, and proceed. We had to lay out a flight plan and say, okay, I think I can go this far this time. If you guessed right, you were okay. If you didn’t … ”

Graduation in December 1955 led to Slayton’s assignment to fighter testing. The presence of another Donald—Don Sorlie—caused confusion in the air-to-ground radio chatter. For a while, Slayton was called “D.K.” and finally “Deke,” a nickname which would remain with him for the rest of his life. Whilst at Edwards, he tested several supersonic Air Force fighters, including the F-101 Voodoo, F-102 Delta Dagger, F-105 Thunderchief, and the F-106 Delta Dart. Shortly afterwards, the Soviets launched Sputnik and the first mutterings of putting a man in space reached the ears of the test-flying community. One day, early in January 1959, Slayton received mysterious orders to attend a classified briefing in Washington, D.C.

Over the course of the next few weeks, he and more than two dozen other pilots were poked and prodded at Dr. Randy Lovelace’s aerospace medicine clinic in Albuquerque, N.M., to evaluate their suitability for Project Mercury, the goal of which was America’s first manned space mission. Still more tests followed at the Aeromedical Laboratory of Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. Many perceived the whole thing as excessive and a waste of time. “I’d flown combat missions and done operational test flying for 17 years by that point,” Slayton wrote. “The fact that I’d survived should have told them everything they needed to know about stress.”

Together with six other top-notch pilots—Scott Carpenter, Gordo Cooper, John Glenn, Gus Grissom, Wally Schirra, and Al Shepard—Slayton was selected by NASA in April 1959 as a member of the United States’ first team of astronauts. Training for Project Mercury was fierce and unforgiving, but after three years Slayton seemed to be in pole position for a flight into space: Assigned to his first mission, he was scheduled to launch in May 1962 and would have spent five hours in orbit, completing no fewer than three circuits of Earth. He picked a name for his spacecraft (“Delta 7”), which was “a nice engineering term that described the change in velocity.”

Unfortunately for Slayton, his own velocity, both in spacecraft and high-performance jets, would decline markedly, thanks to a minor, yet persistent, heart condition, known as “idiopathic atrial fibrillation.” This took the form of occasional irregularities of a muscle at the top of his heart, caused by unknown factors and extremely rare in highly-fit adults. It had first arisen during a training run in the centrifuge in August 1959, prompting NASA flight surgeon Bill Douglas to obtain a clinical electrocardiogram at the Philadelphia Naval Hospital. This concluded that Slayton had a “flutter” in his heartbeat, but further tests verified that the condition should not impair his work as an astronaut.

The problem resurfaced a couple of years later, with speculation that one of the astronauts, perhaps John Glenn, had a heart problem. Apparently, Slayton wrote, the call to Bill Douglas came from Air Force physician George Knauf, attached to NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C., and had originated from “a source higher than the Department of Defense.” Douglas denied that Glenn had a problem. Knauf asked next if Glenn’s backup, Scott Carpenter, had a heart murmur; again, the response was negative. Then, to reinforce the point that the matter was of little relevance, Douglas explained that Slayton had long been known to have a minor heart condition. He expected this to be the end of the matter, but he unwittingly opened a can of worms.

Back in 1959, flight surgeon Larry Lamb had routinely examined Slayton and became convinced that heart fibrillation should disqualify him from the selection process. “He hadn’t said so in 1959,” wrote Slayton, “but he said so now. I don’t think it was anything personal; this was just his medical opinion.” Although Lamb’s judgement was very much a voice in the wilderness, he also happened to be Vice-President Lyndon B. Johnson’s cardiologist and in the spring of 1962 began to question the astronaut’s suitability to fly. (Matters were not helped when the publicity-seeking Johnson was refused access to John Glenn’s home during the latter’s historic spaceflight on 20 February.) In early March, NASA Administrator Jim Webb reopened Slayton’s medical file and the astronaut and Douglas were summoned to the office of the Air Force surgeon-general in Washington, D.C. A panel of military physicians signed Slayton off as fit to fly and their decision was endorsed by Air Force Chief of Staff Curtis LeMay.

For Webb, this was not enough. The Secretary of the Air Force, Eugene Zuckert, insisted that a panel of civilian physicians should also examine Slayton at NASA Headquarters. On 15 March 1962, only weeks before his scheduled launch, Slayton had his heart monitored by Proctor Harvey of Georgetown University, Thomas Mattingley of the Washington Hospital Center, and Eugene Braunwell of the National Institutes of Health. As Slayton waited afterwards, NASA Deputy Administrator Hugh Dryden entered the room and told him, point-blank, that he could not fly. None of the physicians had found a specific reason to keep him off Delta 7, but their consensus was that if NASA had pilots available who did not have his condition, one of them should fly instead. Slayton, not surprisingly, was devastated.

Years later, he was convinced that the decision to ground him was a political one. “NASA knew it would have to publicly disclose my heart condition prior to my flight,” he wrote. “There would be medical monitors at tracking stations all over the world who wouldn’t know how to react otherwise. Everybody expected this to be a big deal. NASA would be opening itself up to a lot of medical second-guessing.” Bill Douglas felt that problems could arise if the astronaut were to start fibrillating whilst on the pad—“do you scrub the launch or go ahead?”—but he was confident that Slayton was the best person to fly.

However, Jim Webb’s fear that it could trigger adverse headlines for NASA drew a line in the sand. “It didn’t matter that a whole lot of doctors thought I didn’t have a problem,” Slayton wrote of Webb’s actions. “He was only going to listen to the few who did.” A launch abort could subject the astronaut to acceleration loads as high as 21 G, and Webb feared the very real possibility that Slayton, dehydrated and perhaps fibrillating, could die during descent. The impact on the agency would be profound.

The next day, 16 March 1962, the grounded and furious Slayton was forced to sit through a lengthy press conference, in which the minutiae of his case were examined. Hugh Dryden remarked that, despite the decision, Slayton might remain eligible for future flights. When a journalist asked if the problem had been caused by stress, Slayton responded no, and further that he did not even know about it until being hooked up to the electrocardiogram in 1959. Bill Douglas’ own departure from NASA within days of the announcement was leapt upon by some journalists as “evidence” of his bitterness over Slayton’s treatment, but in truth he was already at the end of a three-year detachment to the space agency and his return to the Air Force had been in the works since mid-1961.

Despite his grounding, Slayton did not give up on flying. “I made some changes in my lifestyle,” he wrote, “gave up drinking, started working out more regularly—quit doing everything that was fun, I guess!” Douglas also secured him an examination by Dwight D. Eisenhower’s cardiologist, Paul Dudley White, in June 1962. White advised him that two-thirds of people with his condition would die early, whilst the remainder would probably never know they had it and might never be affected. The verdict: “Young man, you’re going to live a long time.” However, White’s report, which highlighted that Slayton did not appear to have a problem, concurred that if astronauts were available without the condition, it would be preferable to assign one of them to the mission.

When it became clear that he would not draw assignment to any of the remaining Mercury missions, Slayton turned his attention to the two-man Project Gemini, at that time scheduled to begin flying in 1964, only to be told that his ailment would make him a “hard sell” to senior management. Shortly thereafter, the Air Force decreed that Slayton no longer met the qualifications for a Class I pilot’s licence—he could no longer fly solo—and, at the end of November 1963, he resigned from the service, with the rank of Major.

Although he would eventually get his ride into space, it would not be until the joint U.S.-Soviet Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP) in 1975. A lesser man might have thrown in the towel and departed NASA for pastures new, but not Slayton. With no guarantee of a mission, he decided to stay, and in the summer of 1962, as the agency prepared to expand its corps by picking nine new pilots, he was appointed as co-ordinator of astronaut activities. NASA’s initial plan to bring in a manager from the outside to oversee the corps was quashed by the astronauts themselves. “What we wanted the least,” wrote Slayton’s contemporary, Wally Schirra, “was somebody who would outrank us and issue orders in a military way. We wanted someone who knew us, who trained with us. Deke was the one and only choice.” As the United States pushed for the Moon, Slayton was all-powerful within the astronaut office, deciding the career paths of the men who would someday walk on the lunar surface … and those who would not.

In this position, he became a virtual father figure to many of them. He was a man labeled “the best” by Mike Collins and described as a dependable colleague who could be trusted “to get the job done, no matter what the job was” by John Glenn. In the words of a Los Angeles Times reviewer—writing on the flyleaf of Slayton’s autobiography—it was indeed “one of the great fortunes of Apollo that [he] was grounded … for in ‘Father Slayton’ NASA had the man who could set the rotations, pick the teams and make the decisions the astronauts wouldn’t have accepted from a bureaucrat or a scientist.”

Even in the early 1970s, Slayton’s chances of ever regaining a pilot’s licence, let alone securing the opportunity to ride a rocket, seemed infinitesimally small. Then, one day in the summer of 1970, during an antelope hunt in Wyoming, Slayton experienced his first heart fibrillation in several months; he had not suffered one ever since flight surgeon Chuck Berry loaded him up on vitamins following a cold. As a personal experiment, he started taking the vitamins again … and the fibrillations went away. “It wasn’t the kind of thing you could use as hard medical evidence,” Slayton wrote, “but it got me thinking that I might still have a more realistic chance.” More than a year later, Berry happened to attend a medical conference in Istanbul and broached Slayton’s case with Hal Mankin, a specialist who agreed to run tests. In December 1971, Slayton flew to Rochester, Minn., and checked into the Mayo Clinic under the false name of “Dick K. King.” Whilst there, Mankin put him through a battery of tests, hanging him upside down on a treadmill, poking holes in him, pumping dye into his system, and examining “parts of my body I didn’t even know I had.” At last, an angiogram yielded the final judgement. “Your man,” Mankin told Berry, “is as good as gold!” Slayton had passed with flying colours, requalified for a Class I pilot’s licence, and in March 1972— now aged 48 and a full decade since being grounded from Project Mercury—he was restored to active astronaut status.

His problem now was getting a flight … and the list of options was short. Two more lunar landing missions were scheduled for April and December, both of whose crews had already been immersed in training for several months. So too had the crews for three flights to the Skylab space station in 1973. For Slayton, the Apollo-Soyuz venture with the Soviets was his last chance. As head of flight crew operations, it was nominally Slayton who oversaw the astronaut selection process, but since he now considered himself a candidate, he asked Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC) Director Chris Kraft to handle the assignment on his behalf. Despite having never flown in space, Slayton was convinced that his seniority would be more than enough to carry him through … and recommended himself for the position of commander. For his crewmates, he identified a pair of astronauts whom he held in extreme high regard: Jack Swigert, a veteran of the ill-fated Apollo 13 mission, and Vance Brand, who was at the time training for the backup command of two Skylab flights.

For reasons explained elsewhere, Swigert’s name was quickly removed from consideration and Tom Stafford—who had served as chief astronaut and had represented President Richard M. Nixon at the state funeral of the Soyuz 11 cosmonauts—entered the story as a real candidate for the commander’s seat. The departure of Swigert also meant there was fierce competition for the command module pilot’s seat, on what would be the last U.S. manned mission until the shuttle era. “Rookie” astronauts Don Lind, Vance Brand, and Bruce McCandless dropped by Stafford’s office to express their interest. Eventually, Stafford recommended Brand, and in January 1973 Chris Kraft called them and Slayton to his office to formally announce them as the crew for the U.S. half of ASTP. Stafford would command the mission, with Brand as command module pilot and Slayton in the new role of “docking module pilot.”

Slayton’s euphoria at finally receiving a flight assignment after such a long wait was tempered by the disappointing news that Stafford would be in command. He remembered that the bittersweet news was “a little deflating,” but understood the reasons behind having a veteran astronaut (and, in particular, someone whom the Russians had grown to trust) in command and acknowledged that “Tom was one of the best.” For his part, Stafford remembered that Slayton was eternally gracious in his new role and there was “never a moment’s tension” over the issue of command. “I told him I knew we had a good crew,” Stafford wrote, “and a good mission to fly and that was as close as we got to talking about the issue.” Yet the fact that on Earth, at least, Slayton remained Stafford’s boss prompted a journalist at the 1 February press conference in Houston, Texas, to ask the obvious question: How did he feel about taking orders from a deputy?

“I see absolutely no problem with that at all,” Slayton replied. “I think there’s a lot of precedence in the country on this particular subject. Anytime you have a guy flying an airplane in the military service, he’s a second lieutenant and you got the highest general in the Air Force. The commander is the commander, and there’s no doubt in this flight who’s going to be the commander. It’s Tom Stafford. Now, when we’re on the ground, working the other programs and the other problems, then obviously we’ve got a normal and working relationship. But I see absolutely no problems at all and I’m responsible to Tom to be ready to fly this flight and he’s responsible to me to see the crew’s ready to go!” At this humorous irony, Slayton’s eyes twinkled and the auditorium broke into laughter.

Yet the fear of further medical problems had not disappeared. NASA’s medical staff insisted on a new flight ruling: If Slayton developed a heart fibrillation during the countdown, the clock would be held at T-4 minutes and he would be extracted from the command module. “Chris Kraft was just livid at this idea,” wrote former flight surgeon Chuck Berry in Slayton’s autobiography. “He called me and asked me what this was all about—[because] he thought Deke was fully qualified to fly.” Berry went to the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas, and assured the doctors there that Slayton wasn’t going to fibrillate on the pad. The rule was unnecessary, he explained, and even if anything untoward did occur, he was a slow fibrillator and would not be adversely affected. Even so, “The Slayton Rule” crept again into the countdown procedures. Incensed, Kraft fired two flight surgeons in the final days before launch and had Berry supervise instead. Tom Stafford was kept informed of what was happening, but elected not to tell Slayton until after the mission.

When Deke Slayton returned to Earth, he gave Berry a gift of thanks. It was the cardiac monitor from his medical harness in the command module, mounted onto a piece of tracing paper, on which was printed the readout of his heartbeat. The beat was steady, with no fibrillations, throughout the flight. …

On 15 July 1975, Stafford, Brand, and Slayton roared into orbit. “Deke felt as if he were riding an old pickup truck slam-banging down a rutted, country dirt road back on his Wisconsin farm,” he wrote in third-person narrative in Moon Shot, a joint autobiography with Al Shepard. “Eight engines blazed away at full thrust with a cacophony of noises—propellants pounding through lines from turbopumps spinning at tremendous speed, pressures surging with booming thuds throughout the stage, all to the accompaniment of teeth-rattling, eye-blurring shaking.” Slayton’s desire to sit back and enjoy his ride into orbit yielded to a sensation of balancing at the end of a long rubber balloon which was fighting its way through wild winds.

“I love it!” he yelled as the Saturn’s first stage burned out and the third stage of their Saturn IB booster picked up the thrust for the final boost into orbit. “Man, I’ll tell ya … this is worth waiting 16 years for!”

“You liked that, huh?” grinned Stafford.

“I’d like to make that ride about once a day!”

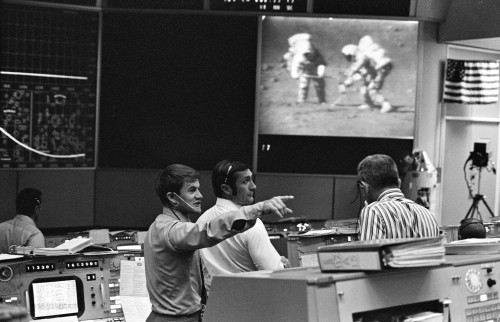

Two days later, the crew rendezvoused and docked with a Soyuz spacecraft, piloted by Soviet cosmonauts Alexei Leonov and Valeri Kubasov. Returning to Earth on 24 July, Slayton’s first and only space mission was completed in just over nine days. As a bitter footnote, a pre-cancerous lesion was spotted on one of his lungs. Thankfully, it was benign and had actually turned up on a pre-launch X-ray, but had been overlooked. Had more notice been taken, Slayton would have been grounded yet again, which would have been the cruellest possible luck. In the aftermath of Apollo-Soyuz, he managed the Approach and Landing Tests (ALT) of shuttle Enterprise and retired from NASA in 1982.

Today, as his mechanized namesake—“Spaceship Deke Slayton”—is readied for launch from Pad 0A at the Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport (MARS) on Wallops Island, Va., one of the reasons Orbital Sciences Corp. chose to honor Slayton is that he pioneered commercial space exploration. In his post-NASA life, the astronaut served as president of Space Services, Inc., developing small rockets for commercial payloads, and under his leadership the Minuteman-based Conestoga booster was built and first launched in September 1982. It became the world’s first privately financed rocket to reach space, achieving a peak altitude of 190 miles (310 km). Only three launches were achieved with the Conestoga, two of which failed to achieve orbit, and the program ended in 1995.

Slayton, meanwhile, was diagnosed with a malignant brain tumor in 1992 and died on 13 June 1993, aged 69. Married throughout the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo eras to Marge, with one son, Kent, he subsequently married Bobbie in his post-NASA life and she survived him. During his military and civilian life, Slayton was awarded the Collier Trophy, the James H. Doolittle Award, and has since been inducted into the U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame and the National Aviation Hall of Fame. A cancer center in Webster, Texas, honors his name, as does the main stretch of road in League City, Texas. Close to his hometown of Sparta, Wis., the Deke Slayton Memorial Space & Bicycle Museum contains his Mercury space suit and his posthumous Ambassador of Exploration Award. And today, on 27 October 2014, in the year that Donald Kent Slayton would have turned 90, he will once again reach for the stars. His story, at last, has come full-circle.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace