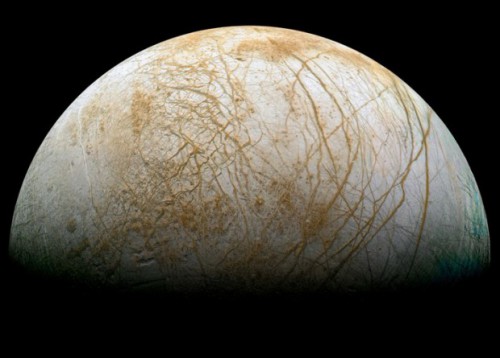

Jupiter’s moon Europa is a fascinating little world, but particularly so for one reason: water. It’s deep alien ocean underneath the surface ice is reminiscent of our own planet, and since our oceans and seas are teeming with life, even beneath the ice at the poles, could Europa’s ocean also harbor life of some kind? Now, another discovery shows that Europa may be similar to Earth in yet another way, and one that could bolster the chances of life even more: plate tectonics. The new results were just published in Nature Geoscience on Sep. 7, 2014.

Why is this significant? It means that the icy surface may be connected to the ocean below; plate tectonics can provide a way for nutrients to be carried from the surface down into the waters below, just as they do on Earth. Even microbes themselves might be able to make that journey.

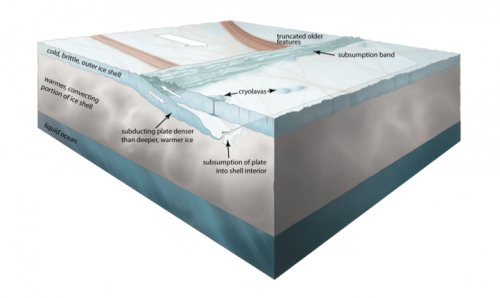

The discovery was made by Simon Kattenhorn, a geologist previously at the University of Idaho in Moscow, and Louise Prockter, a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Md., after looking through photographs from the Galileo spacecraft, which orbited Jupiter from 1995 to 2003. The separate images were treated like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. Since the surface is covered with ridges, bands, and cracks, the scientists could trace back how the broken-up pieces used to fit together, something like continental drift on Earth. “When we moved all the pieces back together, there was a big hole in the reconstruction, a sort of blank space,” says Kattenhorn. Missing pieces, the scientists concluded, probably sank downward, just like tectonic plates can override each other on Earth.

According to planetary scientist Alyssa Rhoden, a NASA postdoctoral program fellow, “What’s exciting is that this would be the only other place outside of Earth where a plate-tectonic-style system is occurring.”

Scientists have known for some time that Europa has a relatively young surface which is being replenished somehow by new, fresh ice. It is thought that this ice is coming up through features called dilational bands, which are long cracks on the surface. There are thousands of them, making Europa look like a giant cracked eggshell. The new ice also keeps Europa’s surface remarkably smooth with very few craters.

The new studies now suggest that the dilational bands behave in a similar way to Earth’s tectonic plates. New ice rises up through the cracks to the surface, but where does the old ice go? “Unless Europa has been expanding within the last 40 to 90 million years, there has to be some process on this icy moon that’s able to accommodate a large amount of new surface area being created at dilational bands.”

That process would be similar to what happens along mid-ocean ridges on Earth, where crustal tectonic plates meet together. New crust, or in Europa’s case, ice, is forced upward through the spaces between the plates where it forms newer crust. Older crust in turn is then forced back down into the Earth’s mantle in places where a continental plate meets an oceanic plate. In this process, called subduction, the oceanic plate is pushed below the continental plate. This whole exchange is an efficient global recycling between old and new material.

All of this is important, since organic material, also just found on Europa’s surface for the first time, and nutrients could then have a way of making it down below the surface and into the water deep below. This of course has a direct bearing on the possibility of life in Europa’s ocean. Minerals necessary for life are likely present on the rocky ocean bottom as well, since the rocky mantle is thought to be in direct contact with the ocean water just like on Earth.

There may still be another explanation for the observations, but this and other evidence continues to show that Europa is a geologically active little world instead of just a frozen ice ball as once believed. And maybe, just maybe, a living one as well.

The findings are also interesting in terms of another potential discovery, of plumes of water vapor on Europa, perhaps similar to those on Saturn’s moon Enceladus. If confirmed, they would provide more evidence that the water from deep below is able to make it to the surface, at least at certain times or in certain places.

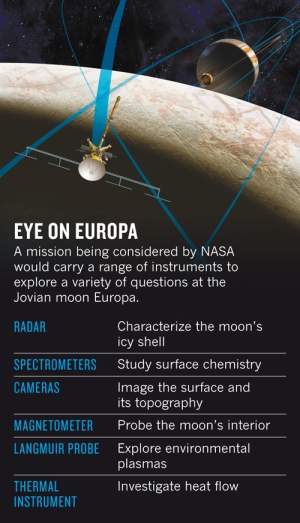

Learning more about Europa’s tectonics and the ocean below will require follow-up missions such as the proposed Europa Clipper, which would make repeated flybys of the moon while studying its surface and interior. Other missions have also been proposed, although it is likely that costs may be a limiting factor. There is, however, a big push happening now for a return mission to Europa that could help answer some of the long-standing questions—primarily, is or was there ever life there?

For a detailed overview on the search for life on Europa, see these related articles “Living On the Edge: Life Under the Ice (Part 1)” and “Living On the Edge: The Inviting Waters of Europa (Part 2)“ by Leonidas Papadopoulos.

The published study is available here (by purchase or subscription) and a Supplementary Information PDF file is available here (free).

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

I processed the global view of Europa and it is a copyrighted image.

I don’t mind you using it, but I would like to be acknowledged. It has been used previously on AmericaSpace (rotated 90 degrees), but in this case I was acknowleged http://www.americaspace.com/?p=45440

Regards,

Ted Stryk

Hi Ted,

Adjusted caption accordingly.

– Mike Killian

Thanks so much. And sorry for the misspelling in my comment. I enjoyed the article.

It’s encouraging to note the high volume of information gleaned from Europa. Both Paul and Leonidas deserve much credit for generating interest in the scientific community to press ahead with various Europa missions. Hopefully, sooner rather than later.

Sorry Ted, I missed that! Fixed now I see though. 🙂