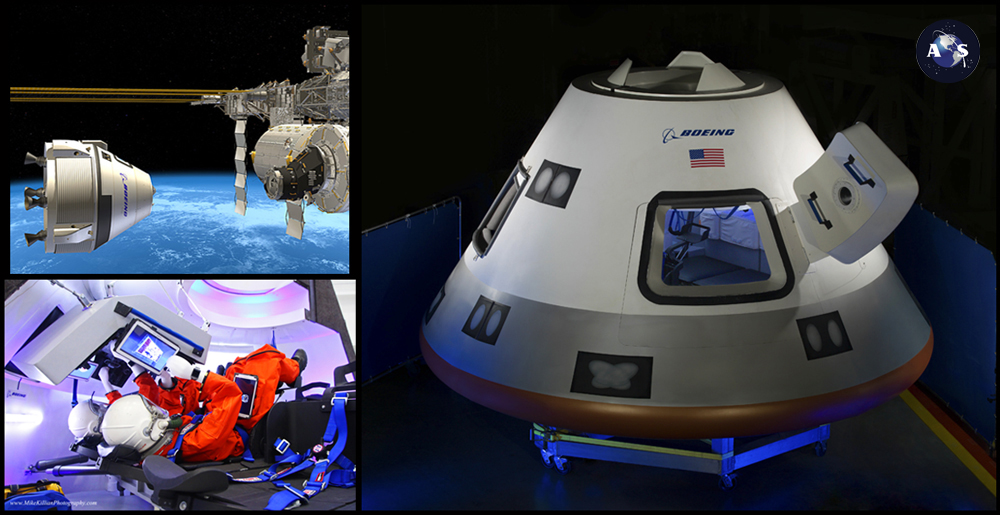

One of three commercial spacecraft currently being developed under a NASA-funded competition to replace the agency’s now retired space shuttle fleet may have just sealed the deal in their effort to earn award of a commercial crew contract to return human spaceflight capability back to the United States. Boeing’s Crew Space Transportation capsule, or CST-100, is the company’s choice to provide NASA and the United States with a new mode of American-made transportation to and from the International Space Station, and last week the company became the first—and thus far only—company to complete its CST-100 Commercial Crew integrated Capability (CCiCap) agreement with NASA, both on time and on budget.

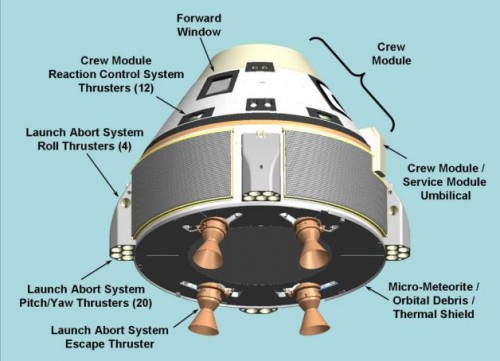

Specifically, Boeing completed the final two remaining milestones under its 20-Milestone CCiCap agreement with NASA. The first was CST-100’s Phase Two Spacecraft Safety Review, which included an overall hazard analysis of the spacecraft, identifying life-threatening situations, and ensuring that the current design mitigated any safety risks. The second was the Critical Design Review (CDR) of the spacecraft’s integrated systems.

“The CDR milestone marks a significant step in reaching the ultimate design that will be used for the spacecraft, launch vehicle and related systems,” noted Boeing in a statement released last week. “Propulsion, software, avionics, landing, power and docking systems were among 44 individual CDRs conducted as part of the broader review.”

“The challenge of a CDR is to ensure all the pieces and sub-systems are working together,” added John Mulholland, Boeing Commercial Crew program manager. “Integration of these systems is key. Now we look forward to bringing the CST-100 to life.”

Bringing the CST-100 to life, however, is a decision that will ultimately be left up to NASA, and the space agency is expected to announce in the very near future which company, or companies, they will select for award of a Commercial Crew Transportation Capability (CCtCap) contract to return low-Earth orbit human spaceflight capability to the United States by the year 2017.

Boeing has remained rather low-key in the development of their spacecraft, or “space taxi” as they refer to it, which makes sense because that is exactly what it is, and although the aerospace giant can now claim the right as the only company to complete its CCiCap agreement with NASA on time, it’s important to note that the milestones Boeing submitted to NASA for CCiCap were far more conservative than competitor SpaceX, who was recently granted an extension by NASA to complete their CCiCap milestones for their crewed Falcon-9 and Dragon-2 capsule by spring 2015.

Boeing also received the biggest CCiCap award dollar amount, which totals $480 million (compared to $460 million total award for SpaceX and $227.5 million for Sierra Nevada). It’s also worth noting that each of the three CCiCap competitors designed their own CCiCap milestones, which were reviewed and approved by NASA prior to solidifying their agreements. Fellow competitor Sierra Nevada also recently requested, and received, an extension by the agency to complete their CCiCap milestones by next spring for their Dream Chaser spacecraft.

The Spacecraft

“The CST-100 is a cheap, cost effective vehicle that doesn’t need to be luxurious because it only needs to hold people for 48 hours. It’s a simple ride up to and back from space,” said former astronaut and commander of the last space shuttle mission Chris Ferguson, who now serves as Director of Crew and Mission Operations for Boeing. “Our focus right now is making sure we build the vehicle the right way.”

Boeing’s CST-100—if NASA chooses to fund it into reality—will launch initially atop ULA’s Atlas-V rocket and be capable of ferrying a crew of up to seven astronauts to and from the ISS. NASA only requires seating for four, but in a recent interview with AmericaSpace, Ferguson said he expects crews of at least five to fly. The vehicle will launch from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, just a few miles from its processing facility, and will cruise autonomously on a six to eight hour trip to the $100 billion orbiting international research laboratory. The astronauts will not need to fly the vehicle themselves at all, and will literally be along for the ride in all aspects of the flight. They will, however, be able to take manual control of the CST-100 at any time, just in case.

“We [Boeing] have a basic level of training we provide that will give the operator, a pilot, the knowledge that they need to operate the spaceship, which is mostly autonomous,” added Ferguson. “They will have the ability to get to the ISS and back, as well as the ability to deal with failures and the ability to take manual control if necessary. NASA wants a single piloted vehicle, so we will train the pilot to whatever level of proficiency they need, and if NASA wants us to train someone else to a pilot level of proficiency then we will be happy to do that. That being said we have factored into our design the ability for a copilot, and train them perhaps to the same level of proficiency as the pilot. They would sit beside the pilot and do all of those types of crew resource management (CRM) types of things that NASA instilled in us shuttle astronauts over the years.”

“When astronauts go up in this (the CST-100) their primary mission is not to fly the spacecraft, their primary mission is to go to the space station for 6 months, so we don’t want to burden them with an inordinate amount of training to fly our vehicle,” added Ferguson.

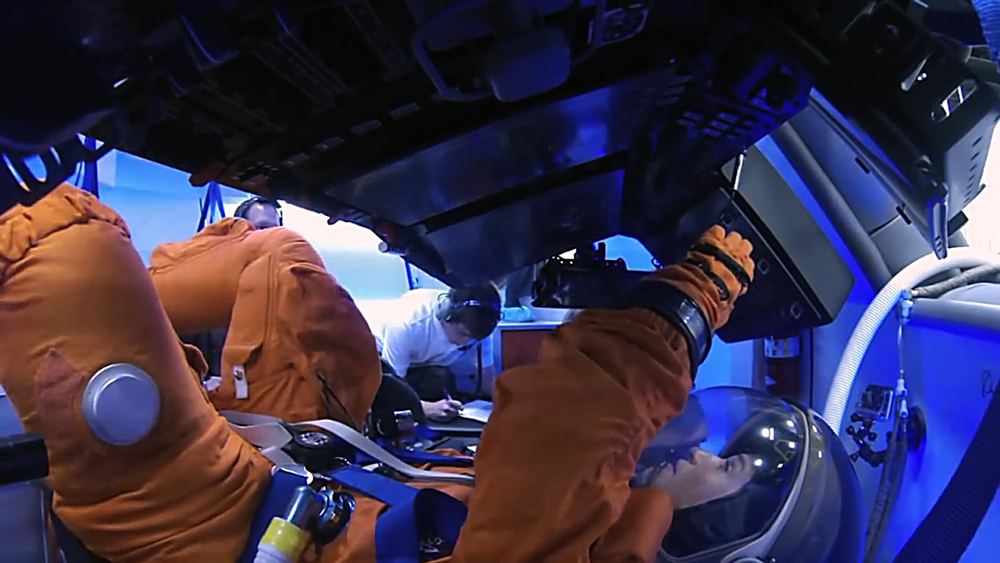

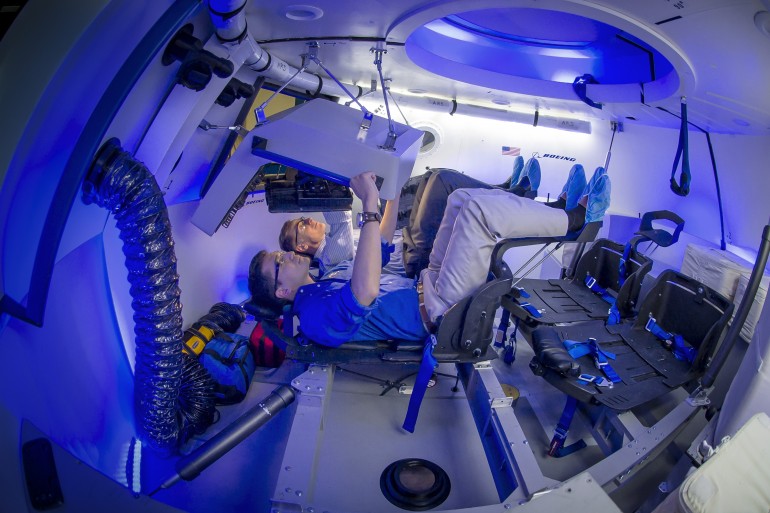

The spacecraft interior is much more user-friendly than vehicles that came before, no more hundreds (if not thousands) of switches on nearly every wall; CST-100’s control panel spans not more than three feet wide. Its look and feel is very user-focused, featuring therapeutic Boeing LED Sky Lighting technology similar to that found in the company’s 787 Dreamliner. A blue hue creates a sky effect and makes the capsule appear and feel roomier, something any astronaut will agree is always desired (spaceflight is not for the claustrophobic). The interior also boasts tablet technology for crew interfaces, which completely eliminates any need for bulky manuals, while wireless internet will support communications and ISS docking operations.

“One of the great things with the technology we have at Boeing is the ability to rapid prototype the interior, and as designs get updated we’re able to bring in new design concepts,” said Boeing CST-100 engineer Tony Castilleja in an interview with AmericaSpace onboard Boeing’s CST-100 mock up last June at KSC. “We get the engineers in here and get the astronauts in here every six months to provide that reach and visibility. Do they feel comfortable? Is there anything we need to tweak as we move forward? It really builds trust with them. It’s almost like buying a car, but you’re a part of the design process in that vehicle.”

“We brought our commercial airliner feel into the CST-100, and so you see this merging … it’s almost like history repeating itself, from commercial airlines to commercial spaceflight,” added Castilleja. “We’re bringing that Boeing element into spaceflight and wanted to create an interior that makes the spacecraft feel a little bit bigger.”

Awaiting NASA’s Commercial Crew decision

If NASA selects Boeing to continue with CST-100 development in the final phase of the agency’s Commercial Crew Program effort this summer, known as CCtCap, then Boeing would immediately move their operations to the Kennedy Space Center to manufacture, assemble, and test the actual CST-100 flight article.

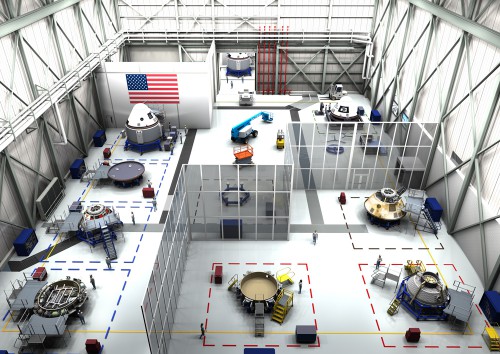

Boeing, in partnership with Space Florida, is already leasing the former space shuttle Orbiter Processing Facility Bay-3 at Kennedy Space Center to do this, modernizing the facility (now known as the Commercial Crew and Cargo Processing Facility, or C3PF for short) to provide an environment for efficient production, testing, and operations for the CST-100 similar to Boeing’s satellite, space launch vehicle, and commercial airplane production programs.

“We’re transitioning this facility into a world class manufacturing facility,” said Mulholland. “With a 50,000 square foot processing facility it’s going to allow us to process up to six CST-100′s at a time.”

The hangar facility has more than enough room to support processing of multiple CST-100s simultaneously, and the adjoining sections of the building are well-suited to process other systems such as engines and thrusters before they are integrated into the main spacecraft. If Boeing advances with CCtCap this fall, it would also mean the addition of 300-500 new jobs to support CST-100 manufacture and processing.

“This facility will become point and center, we’ll be developing the test articles here and then starting the manufacturing for full services in 2017,” added Castilleja. “This is where all the pieces and parts will come in, and we’ll then build everything right here. One side of the building is for processing the service modules, and the other side of the facility is for processing the crew modules. We’ll then ship out to the Atlas launch pad integration facility and off we go.”

ULA is also awaiting NASA’s decision, as the launch provider for both SNC’s Dream Chaser and Boeing’s CST-100 is ready to break ground to build a crew access tower for both spacecraft at the company’s nearby Cape Canaveral Atlas Space Launch Complex-41, just a few miles south of CST-100’s processing facility. ULA will break ground to begin construction in Sept., and estimates 18 months to finish the project, all the while still launching Atlas rockets for their NASA and government customers (ULA has 14 Atlas launches from SLC-41 on the manifest over the next 18 months).

“We and Boeing and ULA are working together to do the tower work as necessary,” said SNC Space Systems Vice President Mark Sirangelo in a recent interview with AmericaSpace on development of the Dream Chaser. “It’s a three way thing and we (SNC and Boeing) are both working together cooperatively with ULA to make it happen.”

Since 2010 NASA has given $1.5 billion to foster the development of a commercial crew spaceflight capability, and the space agency has expressed its wishes on multiple occasions to award commercial crew contracts to at least two companies, but that will be dependent on whether or not Congress provides adequate funding. The expectation is that NASA will award contracts to two companies, and there is much speculation that the company not selected will continue to develop its crewed spacecraft through an unfunded Space Act Agreement.

As good as things look for Boeing, the company is preparing for the possibility that NASA will not award a contract to fly the CST-100, as the company recently sent out potential layoff notices to more than 200 of its employees involved with CST-100’s development, a move stated by Boeing Commerical Crew program manager John Mulholland as “a standard way to minimize potential business impact, it would be hard to close a business case without that backstop of NASA development funds.”

Since the retirement of the space shuttle, NASA has been forced to buy seats for America’s astronauts to fly to and from the ISS on Russia’s Soyuz space capsule, at a ridiculous cost of over $70 million per seat. NASA’s Commercial Crew Program is aimed at eliminating our dependence on Russia and allowing commercial companies to carry out ISS crew and cargo transport, while NASA focuses on developing the Orion and Space Launch System for deep-space human exploration starting next decade.

Check back regularly for updates.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

I think that the CST-100 and the SNC Dreamchaser should get the award.

While SpaceX is doing great work, it has yet to bring the Falcon9 up to the level of reliability that’s needed for human launches. Yes, Falcon9 has gotten to orbit with each launch, but those launches are very rarely on time and there just hasn’t been enough of them compared to the on-time and on-target repeated performance that the Atlas V vehicle offers.

Won’t the next contract simply be decided on business terms ie a tender to supply staff to the ISS?

So number of launches per year, $ per seat, saftey, reliability etc

No, the next round, CCtCap, is another (the last, perhaps?) phase of the the CCDev program. The actual contracts for service, where bidders would commit to a number of launches at a particular price, is a separate process.

If the chronology of COTS/CRS is any indicator, the operational service contracts may not necessarily have to wait for the conclusion of CCtCap. That said, I would be very surprised if the awarding of operational contracts precedes the in-flight abort tests by all parties.

I often think the same, but then there’s the fact that they’d be relying on a single rocket type. If they truly want to hedge their bets against losing the ability to fly they should require one of these vehicles to go up on an LV that isnt powered by Russian tech.

I like the idea of CST-100 on the Delta IV, since it’s all Boeing built, but that’s probably an impractical wish at this point. The better bet if SpaceX doesnt move forward is to have one of the competitors at least do an in depth study on launching with F9.

It’s a hard choice to be sure, but that scenario would at least give SpaceX the experience of launching people, and would provide the necessary funds to keep tinkering on Dragon v2 until the next round of Comercial Crew contracts become available for competition.

WHO YOU TRYING TO KID ? THEY HAVE NOT EVEN FLOWN SUB-ORBITAL EVEN OR GOTTEN TO THE SPACE STATION ! SPACE X WILL WIN HANDS DOWN

Did you bother to read the facts presented in this article, NASA doesn’t care that SpaceX is flying Dragon cargo runs, neither does anyone else, because that was never a prerequisite for CCP & Dragon is not the same as Dragon 2. Also, Boeing doesn’t need to prove their worth, they did that during the last 50 years of human spaceflight, and ignoring the fact that they are now the FIRST and ONLY company DONE with CCICAP all but solidifies there place in CCTCAP.

Lots of ScrubX folks going to be very unhappy pretty soon…

I think the important aspect of this is competition. I think NASA needs all of these options as it can lead to price reduction. I thought that was the whole idea behind the commercial program?

Having three (or for that matter more)competitors for a market consisting of only two flights a year will not reduce cost. It will(absent government support) put two of the competitors out of the business.

If a more robust Humans to LEO market ever develops, government subsidies will not be needed. Until then “commercial” crew is another government program (with some differences in management techniques) and the current market will only support one provider at costs that will still require government support.

Joe,

“If a more robust Humans to LEO market ever develops, government subsidies will not be needed”

Yes and there is the real place for SpaceX !!! Not doing government contract work with its…. 638 stakeholders…

Exactly right Joe. Everyone talks as if a robust humans to LEO market already exists. If such a market existed, the Wall Street financial analysts and advisers would be beating down the doors to get in on the ground floor. The commercial airlines with large, well-established customer bases seem to be in dire straits, charging an extra fee for everything but bathroom tissue in the restrooms. After the billionaires send up all the millionaires who want to go on a sub-orbital joy-ride or a weekend jaunt to a Bigelow Balloon, Joe Lunchbox isn’t going to be able to afford to go, but he’ll no doubt have to pay the subsidy bill for those who can.

Mr. Foley, That last Delta flight was scrubbed how many times? I know I watched it!

Yes, I know too because I was there on the Cape for the AFSPC4 launch, a launch which was scrubbed 4 times – 3 of which was weather related.

You can’t compare SpaceX’s long line of technical delays to ULA’s weather delays. I’m sure you can do better than that…

I like Boeing’s no-frills, no-nonsense approach. The CST-100 is a taxi-ride to the ISS, nothing more, nothing less. But let’s not put all our eggs in one basket and issue awards to companies that offer only conical, blunt-end re-entry spacecraft. Besides Boeing, the other award should be issued to SNC’s Dream Chaser. That way the U.S. has two totally different types of rides to the ISS and there is no single-point spacecraft failure in the system.

I’ve heard this argument for years, and it’s never made any sense to me. How does a hypothetical problem in one capsule mean all capsules share that problem?