“What was it we were really celebrating?

Three men who had done what no man before had done?

A technological feat which was believed to be beyond the realm of possibility?

The fulfilment of an age-old dream?

Were we celebrating simply because there had been a long time since we’ve had anything to celebrate?

Or was this something that touched an irrational, unthinking instinct in us all?”

— Laurence Luckinbill, ‘Moonwalk One’ documentary (1970)

Putting humanity’s greatest achievement in the proper historical context, Theo Kamecke’s seminal “Moonwalk One” documentary chronicled mankind’s first steps on another world during Apollo 11’s mission to the Moon in July 1969, while at the same time documenting the world’s varied reactions to this monumental event as it unfolded. As explored in the first part of this article, Apollo 11 was widely perceived at the time as being just the first step in mankind’s continuing expansion into the Solar System—an expectation that in reality was in sharp contrast to the geopolitical reasons for which the Apollo missions were undertaken in the first place. As a result, in the decades following the cancellation of the Apollo program, there has been no shortage of criticism regarding the lack of national vision and leadership that led to the abandonment of human space exploration beyond low-Earth orbit. Yet what most of this criticism often fails to acknowledge is that the most important stakeholder of the U.S. public space program is, by definition, the general public itself. “NASA depends on the will of the people, as expressed through their Senators and Representatives and the President, for its funding and direction. NASA has to take the pulse of the American people and obtain its good will,” states the space agency’s Headquarters Library website. Appropriately, the second part of this article examines the current state of NASA’s budget and whether that could be a result of the public’s views and attitudes toward the costs of human space exploration.

Space and the “wasteful expenditure” meme

Of all the concerns historically surrounding the U.S. space program, there hasn’t been a bigger one than that of funding and the allocation of resources. The main argument that has underlined the opposition toward funding for space exploration, as expressed by a large part of the American public, has been that this money could be better spent to fix much more pressing social issues on Earth, like poverty and the public’s lack of education, instead of being “thrown away” in space. As described in a recent AmericaSpace history series article by Ben Evans, this attitude toward the space program at the time of the Apollo program was reflected in a protest organized by Reverend Ralph Abernathy, head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Arriving at the gates of Cape Canaveral at the eve of Apollo 11’s launch in 15 July 1969, alongside a team of 200 other protesters, Abernathy expressed his vocal opposition to what he considered an inhumane expenditure, in light of the suffering of millions of Americans who remained impoverished. The reply by Thomas Paine, then-NASA administrator, to Reverend Abernathy is perhaps the best answer to this line of argument, which has remained constant throughout the history of the space program, even during periods when the U.S. economy was booming: “If we could solve the problems of poverty by not pushing the button to launch men to the Moon tomorrow, then we would not push that button.”

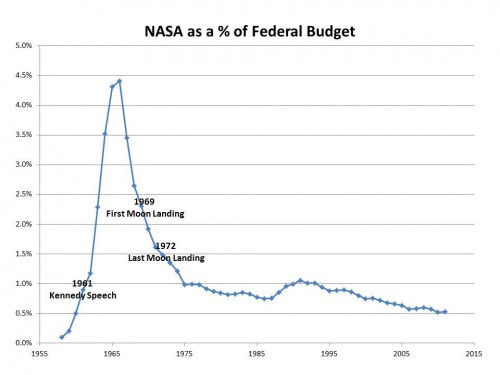

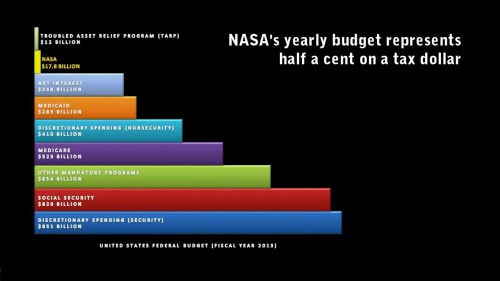

Such financial arguments against space exploration unfortunately come from a lack of understanding on the public’s part of the space program’s value to the U.S. economy and a widespread ignorance of the real levels of government spending on NASA, compared to the rest of the federal budget. Indeed, with the exception of the first half of the 1960s when NASA was allocated an impressive 4 percent of the total federal budget for meeting President Kennedy’s goal of putting a man on the Moon by the end of that decade, there hasn’t been a single fiscal year since when the space agency didn’t have to fight hard for every single penny it received. More specifically, from 1967 onward NASA’s annual budget has been in a steady decline, hovering on average around the 1 percent mark of the federal budget, while plummeting down to 0.5 percent during the last decade, which translates to an amount of $17 billion per year. “If I had a nickel for every time someone said ‘why are we spending money up there, when we have problems down here?'” exclaims astrophysicist Dr. Neil deGrasse Tyson, who has been one of the most prominent science communicators in recent years, as well as a tireless vocal space advocate. “The [current] NASA budget is four-tenths of one penny on a tax dollar. If I held up the tax dollar, and I cut horizontally into it, four-tenths of one percent on a tax dollar does not even get you into the ink!”

Yet there has been a continuing mismatch between the real levels of NASA’s budget and the public’s perception of it. In a study published in the Space Policy journal in 2003, former NASA Chief Historian Dr. Roger Launius observed that “in 1997, the average estimate of NASA’s share of the federal budget by those polled, was 20 percent. Had this been true, NASA’s budget in 1997 would have been $328 billion. If NASA had that amount of money, it would have been able to send humans to Mars. It seems obvious that most Americans have little conception, of the amount of money available to NASA.” This false perception doesn’t seem to have changed throughout the years. A survey made in early 2013 by the non-profit organisation Explore Mars Inc. found that 95 percent of Americans believe that NASA’s budget is somewhere between 0.75-4.11 percent of the federal budget, indicating that many people think that NASA is actually receiving today the same amount of money that it did during the Apollo program in the 1960s. It’s worthy of note that, according to the same survey, when informed about the actual percentage of NASA’s budget, 75 percent of respondents were in favor of doubling it to 1 percent in order to fund a human mission to Mars.

In addition, many of the people opposing space exploration on the grounds of its financial costs fail to acknowledge the actual amount of money that the U.S. has historically spent on social programs, compared to discretionary spending, which includes NASA. According to a report issued in 2013 by the Congressional Budget Office, funding on mandatory spending (which covers the Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid programs) has grown over the past 40 years from 7.5 percent of the U.S. GDP in 1973 to 13 percent in 2012, which translates to an amount of $2 trillion out of a $15.5 trillion-worth of GDP in 2012. “The spending portfolio of the US currently allocates 50 times as much money to social programs and education than it does NASA,” said Tyson during his testimony in 2012 before the U.S. Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation. “So, [the answer to] the old argument ‘why we spend money up there and not down here?’ is ‘we are spending money down here!’ to the credit of the lawmakers understanding where priorities need to land.” Indeed, by examining the numbers in the U.S. federal budget, it is difficult to imagine how the reduction, or even total elimination of that 0.5 percent of the federal budget that goes to NASA, would have any meaningful contribution to the solution of the major social issues facing the U.S. today, or to the reduction of the U.S. budget deficit, as opponents of human spaceflight among the government and the general public alike often proclaim.

Ironically, the Vietnam War, for which the Apollo program was eventually cancelled in the early 1970s, was one of the bigger contributors to the increasing U.S. budget deficit at the time. A report issued in 2010 by the Congressional Research Service, titled ‘Costs of Major U.S. Wars,’ calculated the total expenditure for the Vietnam War between 1965 and 1975 to $738 billion (in 2011 dollars). Furthermore, U.S. military operations in subsequent years have been even more expensive, contributing greatly to the ongoing budget deficit which the U.S. strains to control. “Since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Congress has appropriated more than a trillion dollars for military operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere around the world,” notes the same report. Besides military expenditures, the U.S. government paid trillions of dollars on loans and bail-out packages to support a crumbling financial sector in the aftermath of the 2007 financial crisis. Compared to these expenditures, the cost of the Apollo program of approximately $170 billion (in 2005 dollars), which many have viewed as being the biggest wasteful expenditure in U.S. history ever, can really be seen as a bargain.

Another factor that also escapes the public’s perception regarding NASA’s funding is how insignificant the latter really is when compared to a list of other things the American public chooses to spend money on each year. As it turns out, Americans spend $44 billion on tobacco, $50 billion on alcohol, an estimated $10 to 14 billion on porn, $350 billion on legal gambling, $165 billion on wasted food, and $110 billion on junk or fast food. In addition, it is interesting to note that total spending for Valentine cards in 2014 amounted to $17 billion, while medical costs for cosmetic medical procedures in 2006 reached an estimated $14 billion. Put into context, the money spent by the American public in a single year for all the aforementioned activities nearly equals the total sum of money that NASA has received since its inception in 1958 up to 2012—an estimated $790 billion in today’s dollars.

While the intent here is not to criticize or condemn the activities described above, the latter nevertheless serves as a reminder that NASA’s annual bare-bones funding doesn’t result so much from a lack of resources, but is rather indicative of the American public’s overall financial choices and funding priorities. Several studies regarding public support of NASA have reached a similar conclusion, by also noting that since the electorate and its elected officials form a close feedback loop with the one reacting to the other’s attitudes and vice versa, they both affect the shaping of public space policy. “In [today’s] cultural environment, the general public has defaulted to an attitude reflective of the mid-1950s,” concludes a 2004 NASA-mandated study by the Center for Cultural Studies & Analysis, in Philadelphia, Penn. “They believe space exploration is not a fantasy, but an achievable possibility. They believe it is a noble endeavor. They have a generally positive view of NASA, based primarily on the success of the manned space Mercury and Apollo programs. But they do not believe the government should spend billions of dollars to achieve it.” This belief, in turn, translates to an analogous space policy, according to Dr. Alan Steinberg, a Postdoctoral Fellow of Political Science at the Sam Houston State University, in his 2011 study titled “Space policy responsiveness: The relationship between public opinion and NASA funding.” “Findings suggest that the public supports the idea of space exploration, while also feeling that spending on space exploration is ‘too high.’ Therefore, the government appears to be giving the people exactly what they want in regards to NASA’s budget – more money each year – but at the same time a smaller percentage of the federal budget.”

As with all aspects of public policy, in the end the most important deciding factor for its formation might be the public itself. If the American public really wants a more meaningful space program, it has to demand it from its elected officials. But first it has to be informed about the real challenges and value of the space program and appreciate it in its true dimension. That may constitute a difficult, but ultimately not impossible, proposition.

Video Credit: Callum C. J. Sutherland

You can read Part 3, here.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Leonidas, I am deeply indebted to you for this exceptional anallysis. I will be carrying a hard copy of your series with me so that I can draw it saber-like in response to NASA-bashers. You have done the space advocacy community a very valuable and much needed service with your exemplary work. I am most certainly eagerly awaiting your next article in this series! Thank you very much Leonidas. 🙂

I’m so elated and humbled with your always supportive and gracious feedback Karol! I deeply appreciate it and I’d like to thank you for that.

As the anniversary of Apollo 11 was growing closer, there was this huge mix of thoughts and feelings in my mind that I eagerly wanted to express. And Buzz Aldrin’s #Apollo45 initiative proved to be the catalyst for it. If the articles prove to be interesting and a food for thought, then I couldn’t be happier. The research that I have put in order to prepare them, has proven to be most illuminating for me personally, as well.

My kind regards as always Karol!