KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, FL — Boeing’s CST-100 commercial “space taxi“ will be capable of flying to the space station “as a single piloted vehicle” starting from the first manned orbital test flight in 2017, Chris Ferguson, commander of NASA’s final shuttle flight and now director of Boeing’s Crew and Mission Operations, told AmericaSpace in an exclusive one-on-one interview about Boeing’s human spaceflight efforts to build a private and efficient transporter for American astronaut crews under the auspices of NASA’s Commercial Crew program.

In part one of this series, Ferguson described who will fly aboard the maiden orbital test flight to the ISS in 2017 — here.

In part two, we focus our discussion on the design and training philosophy behind Boeing’s CST-100 capsule.

“The CST-100 is a cheap, cost effective vehicle,” Ferguson explained. “It’s a simple ride up to and back from space.”

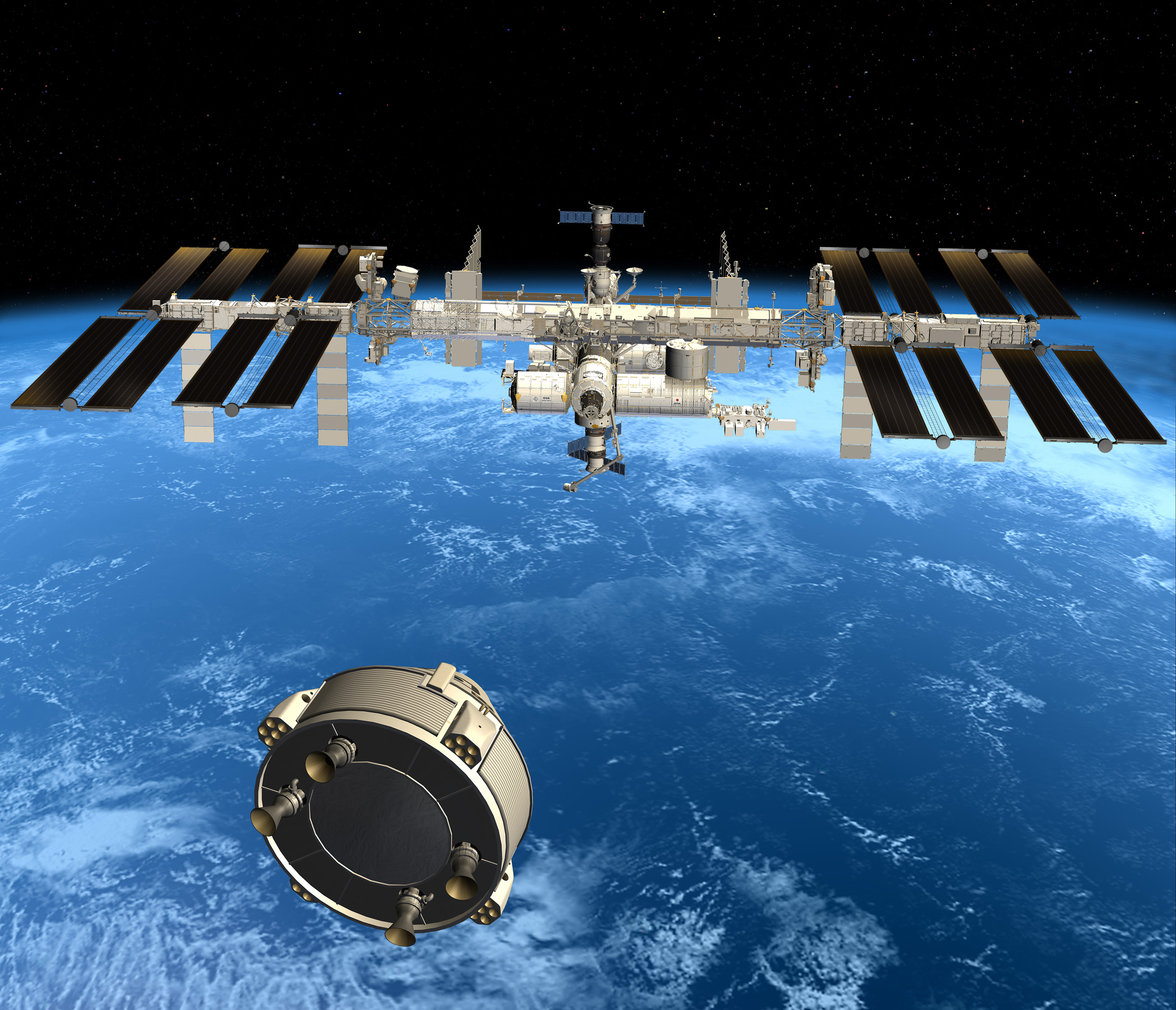

The CST-100 crew capsule is a truly commercial space endeavor—with significant funding from NASA—aimed at restoring an indigenous U.S. capacity for launching U.S. astronauts to low-Earth orbit (LEO) and the International Space Station (ISS) from American soil atop American rockets and seated inside American-made spaceships.

Boeing is designing the CST-100 so that it requires minimal crew training, since it will have a very short flight time and a very simple mission of flying crews to the ISS and back.

“How autonomous will the CST-100 be?” I asked Ferguson.

“We are largely autonomous,” Ferguson explained. “It’s a very simple idea to get the astronauts back and forth because it only needs to hold people for 48 hours.”

“Where did that notion of simplicity in transporting crews to orbit come from?”

“After Columbia, we [NASA] did a crew survivability study in the astronaut office from the crews perspective,” he stated.

“We concluded that the safest way to fly astronauts in the coming decades is to go to a strategy where you separate the people from the payload.”

“The 50,000 pounds of payload part really doesn’t need human rating. So it drives up cost and complexity.”

“The best way, I think even today, is something like the Soyuz concept, where you have a small, cheap, highly reliable vehicle that gets you back and forth to low-Earth orbit (LEO).”

“And then once you are in LEO then go do what you need to do—whether it’s to service something or rendezvous with something like the ISS or an interplanetary vehicle.”

“So let’s get that cheap, cost effective vehicle that doesn’t need to be luxurious because it only needs to hold people for 48 hours. It’s a very simple idea to get the astronauts back and forth.”

“It’s an ascent and reentry vehicle—and that’s all!”

So the CST-100 is basically a taxi up and a taxi down from LEO. NASA’s complementary human space flight program involving the Orion crew vehicle is designed for deep-space exploration.

“Then build your exotic trans lunar vehicle or asteroid vehicle or Mars vehicle and launch that on a separate unmanned booster, and then rendezvous and dock with it and do your mission.”

“The CST-100, it’s a simple ride up to and back from space,” Ferguson emphasized to me. “So it doesn’t need to be luxurious.”

The CST-100 is Boeing’s entry into NASA’s high priority Commercial Crew effort aimed at fostering the development of a safe and reliable, next-generation crewed vehicle to replace the space shuttle after its forced retirement following the final mission in July 2011.

Three-time space veteran Chris Ferguson commanded NASA’s final shuttle flight, STS-135, aboard Space Shuttle Atlantis. It’s now on public view as a museum piece at her final resting spot at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex (KSCVC) in Florida.

Three American aerospace firms—Boeing, SpaceX, and Sierra Nevada—are all vying for NASA contracts to fly astronauts to the space station by late 2017, using seed money from NASA’s Commercial Crew Program (CCP) in a public/private partnership.

The next round of commercial crew contracts will be awarded by NASA around late summer.

“Since the CST-100 will be largely autonomous, can you describe the level of astronaut training required?” I asked.

“We [Boeing] have a basic level of training we provide that will give the operator, a pilot, the knowledge that he needs to operate the spaceship, which is mostly autonomous,” Ferguson replied.

“They will have the ability to get to the space station and back. As well as the ability to deal with failures and the ability to take manual control if necessary.”

“It’s a very short mission. It’s only 48 hours tops.”

“If we have our way we will be docked within six hours in our spacecraft and then be back home in six hours. So it could be tops 12 hours you spend in our spacecraft [including the return trip home].”

“What’s the requirement with regard to doing science and spacewalks?”

“There will be no EVA’s and no science to do. So it’s a very simple mission,” Ferguson told me.

“Can you describe the crew training?”

“So we will train the pilot to whatever level of proficiency he needs. And if NASA wants us to train someone else to a pilot level of proficiency, then we will be happy to do that,” he said.

“NASA wants a single piloted vehicle. Therefore you have to have some form of redundancy. We are largely autonomous.”

“The crew size will be five. We can go to seven if we have to. But NASA only wants four,” said Ferguson.

“What’s the requirement with respect to a copilot? Doesn’t it make sense to have one like on commercial airliners?”

“NASA hasn’t decided yet one way or the other.”

“That being said we have factored into our design the ability for a copilot and train them perhaps to the same level of proficiency as the pilot. They would sit beside the pilot and do all of those types of crew resource management (CRM) types of things that NASA instilled in us shuttle astronauts over the years.”

“That’s what I think will happen as the prudent thing to do.”

“So we will meet the requirements and capability for a single piloted vehicle. But we think NASA ultimately will say we also want someone else trained to the same level of proficiency as the pilot, to back the pilot up and act in the pilots capacity should something happen.”

“So our plan is to train four passengers and one pilot. And the ability to have a second pilot.”

“What is the designation for the other crew members?”

“We are still trying to decide what to call the passengers. We don’t know yet,” Ferguson stated.

“How about ‘mission specialist’ like on the shuttle?”

“The term ‘mission specialists’ is not in NASA’s vernacular now. NASA has called them passengers.”

“The FAA calls them participants.”

“We need a compact thing to call them. So I am advocating for mission specialists.”

“We are getting to the point that we are developing our operational nomenclature and procedures and woven them into flight rules. So we have to make decisions.”

“What term does NASA want to use for the other crew members?”

“We asked NASA but they haven’t gotten back to us yet.”

Boeing expects to be ready to conduct the maiden crewed test flight around mid-2017, comprised of a mixed crew of Boeing and NASA astronauts.

“The first manned test flight could happen by the end of summer 2017 with a two person crew,” Ferguson told me

“There will be one Boeing test pilot and one NASA astronaut,” Ferguson explained. For further details, read part one.

All three company’s currently funded by NASA’s Commercial Crew Program continue to make excellent progress in achieving the agency’s mandated milestones in the current contract period known as the Commercial Crew Integrated Capability initiative (CCiCAP).

The direction and look of America’s future crewed spaceship(s) for ISS operations will become clearer later this year, when NASA down selects to one or more vehicles in the next round of funding known as Commercial Crew Transportation Capability (CCtCap).

Stay tuned here for continuing developments.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace