Last week’s article had focused on examining some of the events and political decisions that have resulted in the U.S.’s reliance on Russia for gaining access to the International Space Station—a topic that came into the spotlight in the aftermath of the recent geopolitical crisis between Russia and Ukraine. Today’s article focuses on some of the decisions that affected the course of the U.S. human spaceflight program for charting a course for deep-space destinations.

Beyond Earth-orbit exploration

The purpose and meaning of human spaceflight has been a subject of debate even before the first human had ever left the Earth to gaze at the infinite blackness of space. Even today, with more than 50 years of history under its belt, human spaceflight is an endeavor that is still in search of a rationale and long-term vision to justify its existence. The advent of the Space Age saw the use of human spaceflight as a mere tool for nationalistic boasting in the international geopolitical arena, or as a source of national pride at best. In this context, NASA’s magnificent and historic accomplishments in space, like the Apollo Moon landings of the 1960s and ’70s, were seen by the U.S. government as just the means for showcasing its technological and political superiority over the former Soviet Union. When it fulfilled this role, the Apollo program was ultimately discontinued and NASA’s plans that called for an aggressive pursuit of human exploration beyond low-Earth orbit and a permanent human presence in deep space were put on hold indefinitely. Despite a number of several failed initiatives that aimed to take up where Apollo left off, the space agency has been more or less left to cast adrift ever since, with no overriding theme about where to go next in space and why.

The Vision for Space Exploration, unveiled by President George W. Bush in 2004 in the aftermath of the Columbia disaster, was one of those ultimately failed initiatives to provide NASA and the U.S. space program with a meaningful direction. After many decades of conducting low-Earth orbit activities, the space agency was directed to return to the Moon and resume a sustainable manned deep-space exploration that had been halted with the end of the Apollo program in the early 1970s. One key aspect of the VSE was to not just repeat Apollo, which featured only a series of limited short-stay visits to the lunar surface. Its underlying premise was to create an infrastructure that would enable humans to learn how to permanently live and work on other celestial bodies like the Moon and Mars, through the extraction and use of local resources.

Unfortunately, the Constellation program, which was NASA’s choice for implementing the VSE, quickly overlooked this critical aspect, and the Moon was seen by the space agency as a “touch and go” destination on the way to Mars. This resulted in Constellation being criticised (partly justifiably) as an “Apollo on steroids”—a simple repeat of what the U.S. had done 40 years earlier, during the Apollo program.

Despite these shortcomings, the Constellation program still provided NASA with a sensible direction and a realistic goal, which was a human return to the Moon in a politically reasonable amount of time of just over a decade. Yet, even though it had been endorsed by two different Congresses in 2005 and 2008, Constellation faced a series of significant technical and financial problems, which led to schedule delays, ultimately throwing the program off track. The Augustine Committee, which was appointed by the newly elected President Obama in 2009 to assess the status of Constellation’s development, acknowledged this reality by pointing out that although Constellation was severely behind schedule, while also facing serious technical issues, these problems could be overcome by a sustained and more robust financial commitment from the U.S. government: “Most major vehicle-development programs face technical challenges as a normal part of the development process, and Constellation is no exception,” wrote the Committee in its final report that was delivered to NASA and the White House.“While significant, these can be considered to be engineering problems, and the Committee expects that they will be solved, just as the developers of Apollo successfully faced challenges such as a capsule fire and an unknown and potentially hazardous landing environment. But finding the solutions to Constellation’s technical problems will likely have further impact on the program’s cost and schedule.”

Nevertheless, President Obama chose the termination of Constellation in early 2010, a program for which he had expressed his disinterest as a presidential candidate in the previous years. By arguing that Constellation was behind schedule and over budget, it appears that the President had probably misread almost the entire history of the U.S. space program. “When the Clinton administration found that the Space Station Freedom program was costing too much and was behind schedule, it opted to restructure the program, bring the Russians in as full partners (it seemed like a good idea at the time), and started the International Space Station,” writes Mark Whittington, an author and space policy analyst for Examiner.com. “The ISS is now in orbit, doing good science, serving as a destination for commercial spacecraft.”

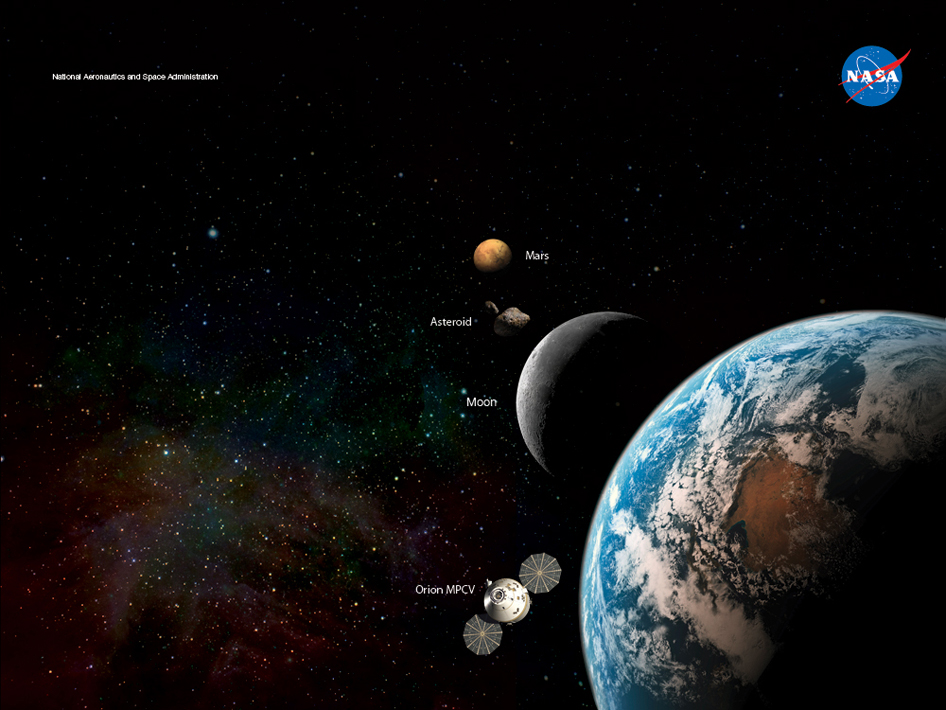

While cancelling a return to the Moon, President Obama announced, among other things, a new set of deep-space goals for NASA: a trip to a Near-Earth asteroid by 2025 and one at the vicinity of Mars by the mid-2030s. This new policy, unlike its predecessor, lacked any definite cost or schedule estimates, an omission for which it received considerable criticism by members of the space community and academia alike. “Here’s the problem: NASA has no firm plan, goals, destinations, and it doesn’t even have the slightest hint of any evidence that a budget significant enough to make Mars exploration possible is in the cards,” writes Keith Cowing, a former NASA employee and editor of the NASAWatch website. “‘Some time in the 2030s’ is not a policy to send humans to Mars. It’s a punchline for policy wonks to use.” Dr. Robert Zubrin, an aerospace engineer and president of the Mars Society, was equally critical. “Under the Obama plan, NASA will spend $100 billion on human spaceflight over the next 10 years in order to accomplish nothing,” wrote Zubrin for the New York Daily News. “Obama called for sending a crew to a near Earth asteroid by 2025 … Had Obama not canceled the Ares V, we could have used it to perform an asteroid mission by 2016. But the President, while calling for such a flight, actually is terminating the programs that would make it possible.”

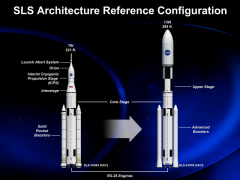

The heated debate that resulted between Congress and the White House over the new space policy unveiled by the Obama administration led to the NASA Authorisation Act of 2010, which, among other things, directed NASA to immediately start working on the construction of a new heavy-lift vehicle, one that would merge the designs of the Ares I and Ares V launchers of the now-defunct Constellation program to a single vehicle called the Space Launch System, or SLS.

Since its inception, the SLS has been severely criticised within the space community, mainly for allegedly being a totally unnecessary, wasteful expenditure for conducting any deep-space exploration. This argument seems to be largely inaccurate, considering that the Space Shuttle-Derived Jupiter DIRECT design, on which the SLS was based, was one of the options being proposed by the 2009 Augustine Committee as alternatives to Constellation’s Ares-I and Ares-V launch vehicles for human exploration beyond low-Earth orbit. One of the findings appearing in the Committee’s report, on which the decision for the cancellation of Constellation was based, was that “the Committee reviewed the issue of whether exploration beyond low-Earth orbit will require a ‘super heavy-lift’ launch vehicle (i.e., larger than the current ‘heavy’ EELVs, whose mass to low-Earth orbit is in the 20-25 mt range), and concluded that it will … Combined with considerations of launch availability and on-orbit operations, the Committee finds that exploration would benefit from the availability of a heavy-lift vehicle. In addition, heavy-lift would enable the launching of large scientific observatories and more capable deep-space missions. It may also provide benefit in national security applications.”

The SLS’s role in NASA’s human spaceflight program has been questioned by NASA’s leadership as well. During a recent hearing before the House Space Subcommittee concerning NASA’s FY2015 Budget Request, Charles Bolden, the agency’s administrator, tied the SLS’s overall value to the ultimate success of Commercial Crew. As detailed in the first part of this article, the Commercial Crew, an unrelated program which aims to develop private space vehicles for transporting U.S. astronauts to the International Space Station, has been a hot topic between Congress and the White House in recent months, following the events surrounding the Crimean crisis in Ukraine. “If I don’t have Commercial Crew and I can’t get to low-Earth orbit, I don’t need SLS and Orion,” said Bolden during the hearing. “If I can’t get to low-Earth orbit, there is no exploration program … I will go to the President and recommend that we terminate SLS and Orion because without the International Space Station, I have no vehicle to do the medical tests, the technology development, and we’re fooling everybody if we think we can go to deep space if the International Space Station is not there. I don’t want anybody to think that I need an SLS or Orion if I don’t have the International Space Station.”

There’s much to disagree with in Bolden’s recent testimony. Yet one has to wonder why the NASA Administrator would want to make such a proposition of canceling the agency’s entire beyond LEO human spaceflight program. One answer could be that since Bolden has been appointed by the Obama administration, he simply goes with the White House’s apparent opposition to the SLS. Yet there may also be deeper reasons that have to do with NASA’s culture itself, as it is shaped today. “NASA has become a master of the space pseudo-event,” comments Dr. Paul Spudis, a senior staff scientist at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, Texas, and a long-time advocate of human space exploration, in his blog Spudis Lunar Resources. “The announcement of a new mission or objective becomes the event. We’re not really going to an asteroid – we’re just announcing that we’re going to an asteroid. We don’t actually have to design the machines and build the equipment to do a mission – we’re on a flexible path. We’ll simply have endless committee meetings and produce PowerPoint shows and high-quality CGI graphic animations of people visiting distant space destinations. The absence of flight hardware doesn’t mean anything – we are developing technology to be able to do it ‘eventually’. The media has become the message.”

Although it can be argued that this assessment of the space agency is not entirely correct, a similar view is shared by many inside the space community, who advocate for an all-private U.S. space program, one where NASA is irrelevant. “While this modus operandi certainly applies to NASA and many of its programs, it equally (and in some ways, more so) applies to many ‘New Space’ companies, whose announcements of spectacular new vehicles, missions and programs continue on a monthly basis,” adds Spudis. “In this sense, New Space is following in the footsteps of its governmental predecessor, only without having previously experienced the latter’s older record of actual accomplishment…New Space companies cheer and proclaim the advent of a new era in spaceflight, but their launch manifests don’t begin to match the pace and predictability of their press releases. Their endless demands to re-direct shrinking NASA funds to them, belies their proclamation of being either ‘new’ or ‘commercial’ … Got a wild idea for a space mission? You say you want to build a vacation resort on Jupiter? Hold a press conference and you’ll have instant credibility as a space ‘entrepreneur’. As for any skeptics in the audience – just ignore them or label them ‘dinosaurs’, ‘old space fossils’, ‘cold-war warriors’, ‘senile’, or shills for government space ‘pork’. Got a difficult question for the space entrepreneur? There’s the exit. Don’t let the door hit you on the way out.”

Despite all the feud between proponents of public and private space programs, a meaningful way forward can be best achieved only by the forging of proper relationships between the two, as evidenced by the success of NASA’s Commercial Orbital Transportation Services, or COTS, that led to the development of private space vehicles for cargo transportation to the ISS by Orbital Sciences and SpaceX.

Even in the light of all these much-needed public-private partnerships, NASA’s role is far from obsolete when it comes to deep-space exploration. The activities that are now undertaken by the private sector in low-Earth orbit were only made possible in the first place because of NASA’s previous pioneering work and overall presence. A market may currently exist for crew and cargo transportation to LEO, but that’s not yet the case with any other deep-space destination, despite all the optimistic projections made by various private companies. “In the history of civilisation, private enterprise has never led a) large, b) expensive, c) dangerous projects, with unknown risks,” said astrophysicist Dr. Neil deGrasse Tyson, during a talk for Big Think. “That has never happened. Because when you combine all these factors, you cannot create a capital market valuation of that activity … Somebody has to draw the maps, somebody has to see where the dangerous spots are, where it’s safe, where the prevailing winds are. Once that is established, then private enterprise can come in, and say ‘here’s the risk, I need an investor, here’s your payback, we can turn this into an enterprise.'” This is a view that is also shared by Spudis. “Governments lead the development of the frontier. Not because it is the ‘right thing’ but because it is the possible thing.”

Considering that the cancellation of SLS would not speed up the development process of Commercial Crew in any significant way—since even if fully funded today the first flights of the private space vehicles that are now under development, according to his own words, will still be a couple of years away—Bolden’s comments that the former is ultimately irrelevant if Congress denies to give more funding for the latter seem really strange indeed. These comments seem more like an attempt on Bolden’s part to toe the party line drawn by the Obama administration, which has always been hostile to the idea of developing a heavy-lift launch vehicle in the first place, than a desire to restart U.S. human deep space exploration sooner rather than later. In addition, President Obama’s rhetoric of investment in NASA’s deep-space exploration program wasn’t followed by similar action. With the cancellation of the Vision for Space Exploration, the U.S. lost not just a launch vehicle development program that was Constellation. It lost a coherent vision statement that clearly articulated where NASA would go next in space and, most importantly, why.

Following the cancellation of Constellation, and despite Congress’ mandate on NASA to develop a new heavy-lift vehicle that has the potential to open up the Solar System to human exploration, the space agency has been left to cast adrift, with no clearly defined vision or a specific mission and direction. The only things that the space agency has been left with during the last several years are a path to nowhere and an absence of leadership.

The opinions presented in this article belong solely to the author and do not necessarily represent those of AmericaSpace.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

If Musk can achieve the reuseability that he predicated …And that is a big if…completely reuse F9 (version whatever) and reuse that hardware 1000 launch life cycle…And launch a F9 for $300,000….Will it mean that he is a great engineering genius or just that the Rocket Technology has matured to this level of redundancy and he is just the first of many to utilize it with the deep pockets? Will history show that NASA, Congress and the other Legacy Companies be considered as having delayed this process? Is the ISS really part of the Space program or the State Department…And the Shuttle itself…Wasn’t it always Version 1 Tech that was never allowed to Mature?

You raise some really interesting questions, Tracy. Indeed, all these are very big ‘ifs’. Only time will tell if all this speculation will turn into reality. Personally, I’m very, very skeptical of that. Until that happens however, all the grand announcements made by the private sector (and NASA) must be critically examined and not be taken to heart just like that, just because a figure of ‘authority’ said so. That’s the problem today – almost everyone seems to be taking every proposed grandiose plan for space exploration as a done deal. That’s not embracing progress. That’s just dillusional thinking.

“And launch a F9 for $300,000”

In early 1990’s the Delta Clipper SSTO program had the goal of achieving an orbital vehicle with a 20,000 lb. payload for a launch cost of $1,000,000. But if you talked to the people working on the project (and I did, was there for several of the DC-X test flights) they would have been happy to reach $10,000,000.

Now after 20 years of inflation, Musk is advertising that he may be able to build a multistage reusable rocket (with all the extra ground handling needed to check out the multiple stages and reintegrate them) for $300,000.

That is indeed “delusional thinking”.

Joe,

I remember watching the video clips of the Delta Clipper as they happened and those were exciting to watch!!!I am a big fan of Musk and but I don’t understand how can he possibly know the reuse lifetime of the engine set and stages without having put one up and brought it completely back down to determine the condition after the affects of launch and de-orbit stresses…Do realistic test chambers exist to project that? I cannot imagine this can be done by firing and re-firing the engines on a test rack can it ?

Tracy,

That is an excellent question. Like most excellent questions answering it fully could take a book, I will try to do an abbreviated version.

There are ways to estimate the service life of engines (and tankage structure) for a vehicle. Those include extensive test stand firings and considerable analysis (hopefully based on actual empirical evidence). The only empirical evidence for reusable spacecraft at this moment is the (much maligned by the “new space” community) Space Shuttle. The shuttle was a very different vehicle than the Falcon 9, but the extensive data on the hardware effects can still be used gain confidence in the validity of the models used for analysis.

That said, you will still not know for sure what the service life of a new vehicle will be until you have flown it multiple times.

There are also many other problems with the reusable Falcon 9 concept (including, but not limited to):

(1) The current scenario has the first stage flying a retrograde maneuver (abating its down range velocity and imparting velocity in the direction of the launch site for recovery). It is questionable whether the Falcon 9 could maintain a positive payload margin (that is put anything in orbit) while reserving the first stage fuel to perform such a maneuver.

(2) The reason I brought up the Delta Clipper is the reference to labor hours required for turnaround of a reusable vehicle. An SSTO was sought in the Delta Clipper program (even though a difficult challenge) because it would simplify ground processing. Even allowing an SSTO the best the Delta Clipper folks could come up with for launch costs was $1,000,000 to $10,000,000 per launch (and they were a very enthusiastic hard working group). The idea that SpaceX could do the same thing (after 20 years of inflation) for anything like $300,000 using what is in reality two different vehicles (the first and second stages) and then reintegrating those stages is extremely unlikely.

There are other problems as well, but I think this should give an idea of the challenges to the likelihood of the reusable Falcon 9’s viability.

Joe,

Excellent comment.

I have been told that if 1) does not work-out, a significant point of SpaceX’s business model for making money goes up in smoke, squeezing the company’s margins downstream. As you point out, there’s a reason SpaceX is hell-bent on getting into the juicy DoD launch business.

For Falcon 9 first-stage reuse, SpaceX tried at first parachutes, which didn’t work. Actually, the chute they used just got shredded as it wasn’t designed for how it was being used. And analysis showed that to get parachutes to successfully work in lowering the Falcon 9 first stage would entail a significant mass penalty that would obviously and negatively impact the payload mass the Falcon 9 could deliver to LEO.

So the idea of flying-back the first stage was conceived. The astrodynamics folks I talk to say that it is one thing to hop around a first-stage on Earth but quite another to reverse the trajectory of such a large object, do so in a controlled manner, and then have enough fuel for a reasonably soft landing. From a mass penalty perspective, this will not be a cheap maneuver.

Thanks again for your comments as they are educating all of us.

Thanks for the compliment. If I may return same, the reporting on this site is educating me as well.

Absolutely EXCELLENT article Leonidas, EXEMPLARY in every way. Your every article seems to be getting better than the one before! Now, prepare for the onslaught of NASA-bashing howler monkeys who will scream the same old tired New Space propaganda that they chant every time you or Jim Hillhouse serve up a dish of the cold hard honest accurate facts. For Newspacers, it doesn’t have to be true, as long as one can get enough people to agree that it is.

Thank you very much Karol, for your supportive feedback!

Indeed, it’s high time that people start awakening to the cold, hard facts as you put it, so that the space program can start going somewhere. Until that happens, we’ll continue down the same road that isn’t really going anywhere.

My friendly, kind regards, as always!

The Augustine Committee also reported that Constellation wasn’t feasible on any sort of budget that NASA could realistically expect to have in the years to come. The author blames the President for concluding that, but he didn’t pull that conclusion out of thin air. It was widely known at the time, and the report merely confirmed that reality.

The circumstances of re-structuring Space Station Freedom to bring the Russians in were quite different from the ones faced by Obama relating to Constellation. Russia were the world leaders in space station technology, there was an on-going cooperative program with shuttle-Mir that was bringing the two programs together initiated by George Bush the First, and there were compelling reasons to keep the struggling Russian space program operating to prevent engineers from selling their talents to the highest bidder.

The situation with Constellation was quite dissimilar. Bringing in the Russians wouldn’t have solved the program’s underlying financial and managerial problems. Probably would have simply made the whole effort more complicated. Not sure what value-added contributions the Russians could have made to any joint effort at that point.

Leo,

I couldn’t agree more as I painfully remember the “lag” of getting any of the ISS work done that part of Russia’s responsibility…And it was setup that they were responsible for key modules that NASA couldn’t get around…I always felt that the ISS was really a part of the State Department…From that standpoint the ISS was a disaster…I cannot believe why this same thinking is being applied to a mission to Mars as I constantly hear in the media that Mars will take an International Team to achieve because of the high costs involved…This is going to be another State Department Project…Unfortunately

To cover some of the points made:

The VSE failed due to (1) lack of public commitment and interest by the Bush 2 administration and (2) the fateful appointment of Dr. Griffin, who, while a superb engineer, led NASA away from the effective path of developing reusable hardware to use for BLEO exploration, and back onto the dead end path of giant expendable rockets and capsules. An Apollo style mission is a dead end since the astronauts have no substantial set of equipment to DO anything once they reach a destination.

The cancellation of Constellation was deemed an “easy decision” based on the pace of the program and the available level of funding, by former NASA deputy administrator Lori Garver, who has been a supporter and friend of the human space program since the 1980’s. The problems faced by Constellation were much larger than the typical NASA budget overrun, especially since there would be no larger budget to compensate.

The endorsements of the Constellation and the its stand-in, the SLS, especially since 2010, are primarily a creation of a small clique of Senators and Congressmen whose districts benefit from the continuing and pointless funding.

While it is true that heavy lift vehicles will be needed for BLEO exploration within 15 years, we do not need them right now, what we need is US access to orbit. In this issue Bolden is dead on target. The issue is not for or against an HLV, but instead for or against an EXPENDABLE HLV that will be too expensive to use for BLEO exploration. The only solution for the kind of large scale, high mass operations we need is for reusable boosters, whether the size of current rockets, HLV sized, or even super-HLV sized. Development of such boosters can push launch prices down to between 100 and 400 dollars a pound, compared to the current price range of 2500 to 8000 dollars a pound.

The major mistake most of those arguing for one space destination and against another is that without reusable boosters and spacecraft, along with bases, depots and crew refuges to support them, none of the destinations will ever be reached.

Those who claim that advocates of launch privatization want to make NASA irrelevant ignore the fact that companies need customers to fund their operations. Who else but NASA would be able to fund pure exploration operations. Launch privatization could actually increase the number of NASA employees working on developing and operating vehicles in space, including increased use of the space station. The only funds that are currently being wrongly redirected are those stolen from the Commercial Crew program and given to the SLS.

The plain fact is that as long as SLS funding continues to prevent development of BLEO hardware and vehicles, there will be NO progress toward BLEO exploration, and the “space pseudo-events”, including some staged to provide political support for the SLS itself, will continue to be the only form of “progress” in space.

.

John,

Good points…It almost looks like a “certain group” does NOT want anyone to get BLEO in any meaningful way…

Tracy,

The problems with the Augustine Commission are multiple, not the least of which are people with misunderstandings of what it actually said. That is in evidence here.

Rather than take up bandwidth, here is a link to a (fortuitously) contemporary article by Dr. Paul Spudis discussing exactly that subject.

http://www.spudislunarresources.com/blog/international-repercussions-part-1-the-unreliable-partner/#comments

I wholeheartedly agree with you Joe. Having been a reader of the posts on AmericaSpace for some time, is is readily apparent that there are always some individuals who constantly repeat the same erroneous statements and promulgate misinformation be it about the Augustine Commission or launch vehicles that have not yet flown regardless of how many times a Leonidas, Jim Hillhouse, or Joe provide concrete evidence to the contrary. Apparently they believe that if they just repeat it often enough, and they can get others to do the same, it will somehow become true. It must be a truly marvelous world in which to live.

Thank you, Joe, for the link. Dr. Spudis is one of the foremost experts on this subject.

Joe,

I went to the link and was surprised to find that the entire world except the US thinks we should go to the moon but the US says no we need to do an ARM as the next stage toward Mars…I can think of one company that really really really benefits of the ARM project and that company is Planetary Resources…So that helps put things into perspective.

Tracy, from NASA’s Associate Administrator for Human Exploration and Operations, William Gerstenmaier’s comments at the Senate’s Subcommittee on Science and Space recent hearing ‘From Here to Mars’, I take that one of the reasons that NASA is so hell-bent for the ARM mission, is because of funding (or lack thereof). According to his testimony, the only doable mission that fits within the current cost and schedule estimates without the infusion of any additional funding, is the ARM. Whether that’s accurate or not is debatable, but you can hear his comments on the link here, at the 37.55-minute mark, answering to a relevant question made by Sen. Bill Nelson.

Then again, I believe that it also has to do with Obama’s perplexing insistence that the Moon is of no value. ‘Been there, done that’ and the like…

The following is what I hear from sources.

The White House wants ARM, in so far as it wants anything to do with space, which is very nearly asymptotically zero. And the White House has made it clear that either ARM is NASA’s next BEO human mission or there’s another fight over Orion and SLS. After all, the White House would say, if we are not returning to the Moon–this White House is completely opposed to a lunar return–then there’s no reason for those two systems.

So, everyone at NASA puts on a Happy Face and talk-up ARM. The space agency really has no other choice, at least publicly.

Thanks for the clarification, Jim. This is really a sad state of affairs for the space program.

Playing Devil’s Advocate here … There are probably more Americans who absolutely despise even the idea of manned spaceflight than there are passionate advocates of such programs, probably more anti-manned space Americans than anti-Obamacare Americans.

How do you craft a manned space program which satisfies both groups?

– “There are probably more Americans who absolutely despise even the idea of manned spaceflight than there are passionate advocates of such programs”

– “probably more anti-manned space Americans than anti-Obamacare Americans”

Do you have any empirical evidence (polling data, etc.) to support your “probably” list? If not, then you craft a program the same way you would otherwise as your suppositions are “probably “not true.

That is an excellent question that lucidly points out a profound problem facing the space community.

And to answer you question, might I suggest…well, I have no idea. I was at a conference in March and it was shocking that the talk of how to strengthen support for space exploration sounded very close to what I recall Von Braun’s group, the National Space Institute, saying in the late 1970’s. With so little progress, I’m not sure there is an answer.

Maybe trying to sell spaceflight to the country is a lost cause? Perhaps we should just persuade the powers-that-be to run a low key manned space program, with the notion that what anti-spacers don’t hear won’t alarm them.

Which sucks considerably in some moral sense. OTOH, a fair number of the anti-manned space people already think NASA is chewing up a quarter of the federal budget and other people think we’ve been sending astronauts beyond the moon and off to Mars for many years. So simply tring to spread The Faith isn’t enough; there’s a massive deprogramming effort needed before we Enlighten the Heathen — and attempts to educate the public about scientific/technological issues gnerally don’t go well.

Also, we take deep black military and intelligence satellite programs with equanimity, so a little-publicised (“light gray”) civilian space program isn’t all that outrageous a concept. The Bureau of Mines, for example, or the Coast & Geodetic Survey aren’t really secretive, but I’d guess 99 percent of the public has heard of neither, just because they fail to excite many people.

And there’s a thing I heard Scott Pace say at a Marshall Institute panel discussion http://marshall.org/events/americas-space-futures-defining-goals-for-space-exploration/ a couple of months back. A question came from the audience about whether manned space flight could be made a “kitchen-table discussion issue” in American households. Pace responded that this would not help the progress of spaceflight at all; people talk about day-t-day matters at the kitchen table (school work, weather, shopping trips, etc) or they talk about purposefully serious matters (Daddy’s lost his job, Mommy’s pregnant, Grandma is dying, and cousin Bobby got his draft notice). Stick manned spaceflight into that environment, and it’s apt to be viewed as something Dire and Dangerous rather than Delightful, There might be counterarguments to this, they don’t occur to me right now.

Thanks for the soapbox …

We are beset by bean-counters.

Consider, please, what the adversaries achieved in WW2, while blockading and bombing the hell out of each other and with the vast majority of their peacetime experts at war. We built well over half a million significant warplanes, a hundred thousand big tanks, a couple of million 12-cylinder, thousand-horsepower-plus engines to power them, plus warships and submarines and liberty ships galore. And we invented radar and the atomic bomb.

Then America, alone, fought a vicious war in Vietnam while re-equipping SAC with B52s and KC135, switching to the mega-carriers and supersonic fighters . . . and going from not-really-successful sub-orbits to the moon.

What’s ridiculous is that space flight has NOT cheapened greatly. What is holding us down isn’t the gravity well but the craven defeatism of placemen and politicians.

Leonidas,

Do not take this too seriously. Simberg has a very short list of ‘experts” he considers worthy and his own name is both first and last on the list.

Thank you Joe. Actually no, I don’t. Mr. Simberg is entitled to his opinion, as I am entitled to mine. I’m actually flattered that he takes the time to write a whole commentary on something I’ve written.