Since 1957, there have been almost 7,000 satellites launched into Earth’s orbit by various countries and private companies. Their missions range from scientific observation and weather tracking to communications and broadcasting television. Roughly half of those satellites are still in orbit and operational, while the other half has fallen into a state of decay, losing altitude and functionality as equipment ages. What happens to these defunct objects once they can no longer be controlled by human operators from Earth? Some burn up harmlessly in Earth’s atmosphere upon reentry. The majority, however, become part of the ever-growing cloud of human-made debris that now encircles the Earth and jeopardizes both existing infrastructures and future endeavors in space.

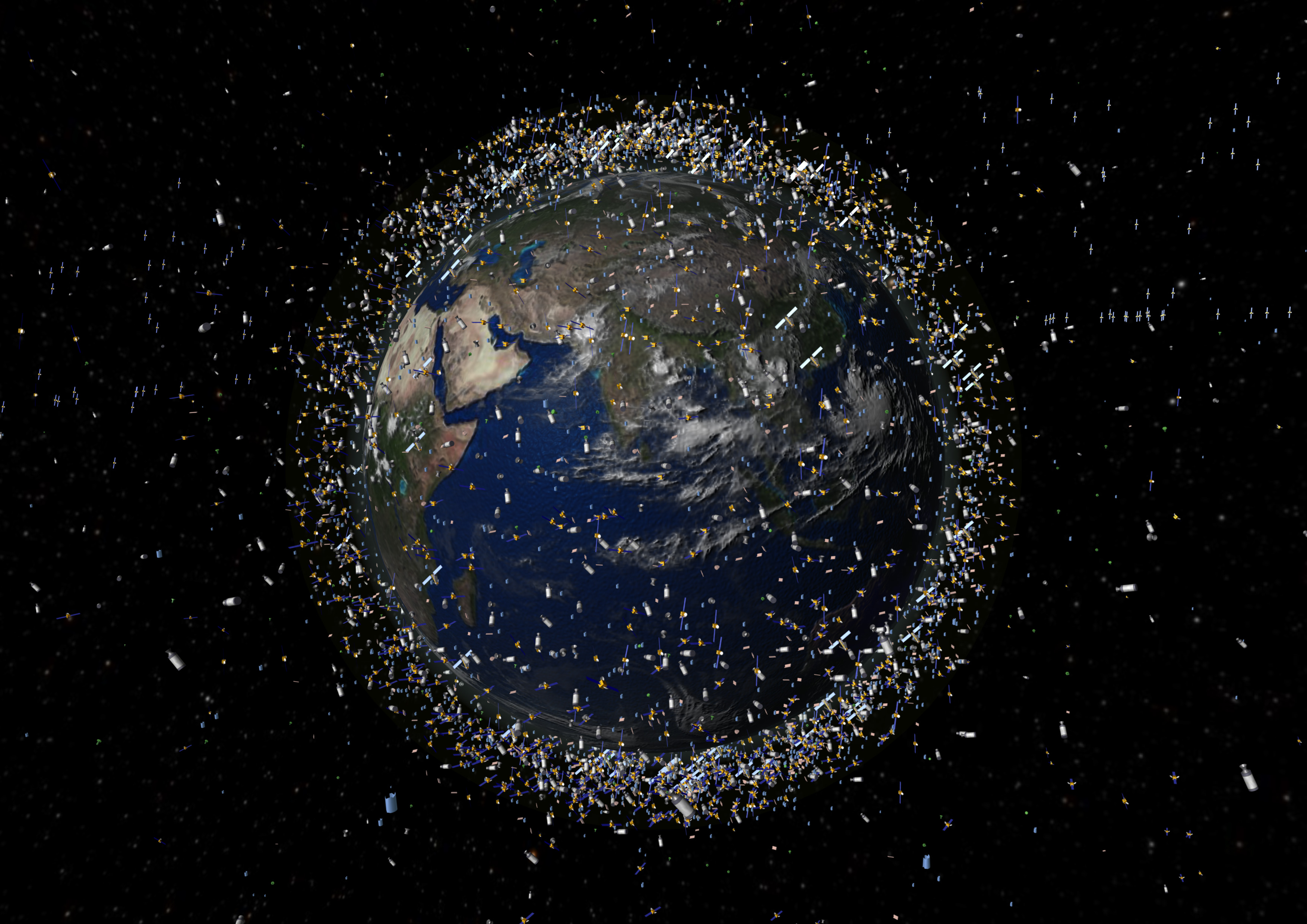

The majority of Earth’s satellites operate within a region known as low-Earth orbit that extends from an altitude of 100 miles (160 km) to 1,200 miles (2,000 km) above Earth’s surface. Almost two-thirds of the roughly 17,000 artificial objects currently being monitored can be found in this relatively small region of space, particularly over the polar regions of the planet. As the number of objects in orbit continues to increase, the risk of orbits becoming congested grows; the potential for collisions between operational satellites and uncontrolled debris also rises. Collision warnings are already regularly issued for satellites operating in polar orbits, with 10 objects per week coming within two kilometers of vital communications satellites.

Containing spent rocket components, dead satellites, and fragments from collisions, the cloud of debris above Earth’s atmosphere continues to grow. NASA estimates that there are some 22,000 pieces of space junk as large as softballs and another 500,000 pieces larger than a marble. The number of fragments at least 1 mm in diameter is somewhere in the hundreds of millions. Hurtling through space at tremendous velocities, even the smallest of these objects could pose a threat to the 1,000 or so operational satellites currently in orbit. For example, the thought of a piece of junk the size of a marble, or smaller, disabling a satellite like HughesNet’s EchoStar XVII or the GPS Block IIA has generated a considerable amount of concern among space officials, since millions rely on these satellites alone.

Every item of space junk also has the potential to further enlarge the debris field through collisions. An additional 2,000 items of debris were created in 2009 when a dead Russian satellite smashed into an active U.S. communications satellite. Another similar incident was barely averted in 2012 when a dead Cold-War spy satellite was on course to pass within 213 m of NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope. Luckily, NASA was able to engage the telescope’s thrusters to create a wider cushion of six miles between the two objects. Collision warnings like these are on the rise, however, with approximately 10 objects passing within two kilometers of active communications satellites each week.

In addition to accidental collisions and explosions, the debris field has also been enlarged by military testing. In 2007, the Chinese military destroyed an aging Fengyun-1C weather satellite using an anti-satellite (ASAT) device launched atop a ballistic missile. The incident is estimated to have generated around 950 items of debris 4 inches (10 centimeters) or larger and some 35,000 pieces larger than 1 cm. Widely viewed as the most prolific single cause of space junk in the five decades humans have been in space, the debris cloud from the satellite now extends through all of low-Earth orbit.

So what can be done to stem the growth of the debris cloud and remove existing objects? One proposed remedy includes venting pressure tanks and depleting excess fuel reserves before an object loses functionality. This will prevent accidental explosions that create even more debris as well as making them easier to track and retrieve. Another option is to maneuver aging equipment and satellites out of congested orbits while they are still under control to gradually reduce their altitude, allowing them to burn up upon reentry. Larger items and dead satellites will require missions to actively remove them from orbit. Special retrieval craft can attach to the object using robotic arms or nets and then induce a controlled reentry using their thrusters.

Immediate action needs to be taken by the international community to address the problem of space junk. If the debris field continues to grow, missions like the planned 2020 Mars rover and the recent Orbital Sciences Cygnus resupply mission to the International Space Station will be at risk. With modern society increasingly dependent upon satellite systems for many essential services, the time to clean up Earth’s orbit is now.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

This isn’t a new out of the blue problem. There’s certainly a lot of talk but little or no action. Why do we always leave things until we’re on the brink? Surely it cannot be purely down to cost can it? Lack of international cohesion?…. Crikey they’re rocket scientists why couldn’t they make sure spent rocket parts made atmospheric reentry? I for one look forward to seeing a firm plan of action finally adopted but certainly still have my doubts.

Yes, it is irresponsible to leave junk in space. However, orbital mechanics keep most of it from being a problem. Gravity was just a movie.

To address the problem we simply need more people in space. Then it will become a priority if it really is a problem. The Chinese intend to lease space on their space station in ten years. I’m betting that Bigelow and others will beat them to it.

We just need a bit more patience.

im just plain fed up

And the cost of the solution shall be based on percentage of debris that the owners of the debris have in space. The cost will be accessed to each contibutor to the debris and paid for by that debris owner. They shall not be allowed to use the orbital highway for any further events until paid.

Early this morning 11.03.13, I went out to see if I could find Comet ISON in my 4″ S/C scope. I was successful @ No. 47 for me! YES! (I was under impressed though – I hope it gets brighter!) During my viewing session I saw 8 satellites, three of which I saw _thru_ my 32mm eyepiece! Of course dusk and dawn are the best times to see *.sat crossings.. but I couldn’t help but think that it looked pretty crowded up there and wondered how many of those were still functional? 50-75%?

I like the idea of painting orbital debris with ground based MASERs to consecutively bombard an object to produce a subtly accumulative propulsive force to eventually modify orbitals…