On Saturday, Europe’s fourth Automated Transfer Vehicle (ATV-4)—named in honor of German-born physicist Albert Einstein—is scheduled to dock at the International Space Station’s Zvezda module. The arrival of the cargo ship, which carries 5,500 pounds of food, water, fuel, equipment, and supplies for the station’s incumbent Expedition 36 crew, marks the second-to-last mission by the highly capable ATV. However, planning is already advanced on future missions which may utilize ATV technology, including a possible role in the Orion Service Module for NASA’s Beyond Earth Orbit aspirations.

Launched atop an Ariane 5 rocket from the Guiana Space Centre in Kourou, French Guiana, on 5 June, “Albert Einstein” is following a standard, ten-day rendezvous profile, preparatory to docking with the expansive orbital outpost. At 44,830 pounds, this is the heaviest ATV ever flown and carries the largest amount of dry cargo ever ferried into space by a European-made vehicle. Measuring 34 feet long and 15 feet wide, it included an Integrated Cargo Carrier for its pressurized payloads, together with an avionics module for its computers, gyroscopes, navigation and control subsystems, electrical power and communications facilities and a propulsion module for rendezvous and periodic “re-boosts” of the ISS orbit. Later this month, Albert Einstein will undergo a test of this re-boost capability, ahead of a full-up burn to increase the station’s orbit on 10 July.

Whilst the ATV is not capable of returning items back to Earth and instead burns up in the Earth’s atmosphere at the end of each mission, it has the capacity to remain docked at the ISS for up to six months and essentially creates a new “room” during that period. To date, four ATVs have flown, all named in recognition of key European-born scientific figures: Jules Verne in 2008, Johannes Kepler in 2011, Edoardo Amaldi in 2012, and the ongoing Albert Einstein mission. A fifth flight, named for Belgian astronomer Georges Lemaître, will close out the program in 2014.

Last April, the European Space Agency (ESA) announced that it was shutting down its ATV production lines. Quoted by SpaceFlightNow.com, senior advisor Bob Chesson of the agency’s human spaceflight directorate explained that “a significance obsolescence problem” existed at equipment and component levels, effectively limiting the desire or ability to reopen the lines. Costing approximately $600 million per unit to build, the ATV was operated as part of a “barter” arrangement between ESA and its ISS partners, covering its operating costs at the space station until 2017. A further $600 million investment was required to cover the 2017-2020 timeframe and Germany apparently favored European participation in the Orion program, with ATV technology used as the basis for the Service Module.

Initial reports of European interest in retasking the ATV to a Beyond Earth Orbit mission arose almost two years ago, when NASASpaceflight.com cited sources which described ESA as “serious” about the possibility. Then, in June 2012, EADS Astrium received a pair of contracts—each valued at 6.5 million euros ($8.6 million)—to undertake studies of an ATV-based Orion Service Module and an entirely separate multi-purpose orbital spacecraft. Finally, last November, it was reported that ESA was prepared to provide the key component as “payment-in-kind” for its continued involvement with the International Space Station through the end of this decade. Earlier this year, it was announced that ESA would indeed build the Service Module for Orion’s first Exploration Mission (EM-1), currently scheduled to launch in December 2017. That seven-day mission will be the uncrewed maiden voyage of NASA’s mammoth Space Launch System (SLS) booster—flying in its first-generation, 70-metric-ton variant—and is expected to perform a full circumnavigation of the Moon.

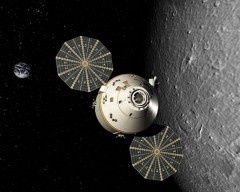

As a result, the physical appearance of the Service Module has changed markedly in recent months. Its previously circular solar arrays are gone in the schematics, replaced by the X-shaped “windmill” arrangement of four panels seen on the ATV. The craft will be a critical component of the United States’ first vehicle to depart Earth orbit in almost five decades. Mounted directly below the crew capsule, it will house the propulsion assets for orbital transfer, attitude control, and high-altitude ascent aborts. It will also generate and store power and provide thermal control, water, and breathable air for the astronauts. Like the Apollo Service Module, it will remain attached to Orion’s crew capsule until shortly before re-entry, whereupon it will be jettisoned and burned up in the Earth’s atmosphere.

It is clear that NASA and ESA share a positive working relationship, which has sown the seeds for this latest endeavor. The two agencies’ partnership in human space exploration stretches back to the early 1970s and the genesis of Spacelab, and they have worked together on Space Station Freedom and the ISS for almost three decades. Speaking in January 2013, Dan Dumbacher, deputy associate administrator for Exploration System Development at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C., noted that “this latest chapter builds on NASA’s excellent relationship with ESA … and helps us move forward in our plans to send humans farther into space than we’ve ever been before.”

Although the inaugural “shakedown” voyage of Orion is scheduled to take place in September 2014, as Exploration Flight Test (EFT)-1, its “test” Service Module has been constructed by Lockheed Martin. The ESA-built Service Module seems likely to be assembled by EADS Astrium in Bremen, Germany, and will consist of an aluminum-lithium alloy structure to support solar arrays, radiators, reaction-control thrusters, oxygen and nitrogen tankage, carbon dioxide “scrubbers,” wastewater recycling systems, and a 7,500-pound-thrust main engine. Present specifications describe the Service Module as a cylinder, measuring 16.5 feet wide and 15.7 feet long, with an empty mass of 8,000 pounds and a propellant capacity of 18,000 pounds.

That marks out the ESA-built Service Module as something quite distinct to the ATV, of similar shape and size, but for a very different purpose. It will carry astronauts far beyond Earth orbit and its systems will be required to keep a crew alive for many months at a time in regions of space beyond our planet’s radiation belts. “This is not a simple system,” stressed Mark Geyer, NASA’s Orion Program Manager. “ESA’s contribution is going to be critical to the success of Orion’s 2017 mission.” Assuming EM-1 is a success, there seems reason to be optimistic that Europe will also be approached to build follow-on Service Modules for subsequent Orion missions—including the crewed EM-2 voyage in 2021, which has caused many mouths to water with excited anticipation in recent months, owing to its destination of either the Moon or a possible rendezvous with a captured asteroid in cislunar space.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter:@AmericaSpace

“Unlike its cousins Dragon, Cygnus and the Japanese H-II Transfer Vehicle, the ATV is not capable of returning items back to Earth”

Neither HTV nor Cygnus can return cargo to the Earth. Only Dragon (and, of course, Soyuz!) have that capability today.

Is it too early to ask what happens after the first MPCV/ATV service module is constructed?

Does ESA transfer the technology to NASA and then NASA constructs; does ESA continue to build the service module; does NASA between now and then fund development of a home-grown service module? Lots of questions but oh such a dearth of answers.

Thanks Jeff. My mind suffered a temporary restart back then. Thanks for the correction.