Thirty years ago this week, the youngest member of the United States’ shuttle fleet took to the skies on her maiden voyage. As described in yesterday’s history article, Challenger had risen from the bones of a structural test article—used to establish baseline thermal and mechanical stress data—and been extensively upgraded to render her capable of traveling into space. Four years later, on 4 April 1983, she was finally ready to go. Juxtaposed against Challenger’s youth, however, were the combined ages of the four men who would ride STS-6, call her home for five days, spacewalk from her, and launch a giant NASA communications satellite. Commander Paul Weitz had wryly dubbed his crew “The F-Troop” … but the jokesters in the astronaut office countered with their own moniker: Geritol Bunch.

The F-Troop nomenclature came from a television series about an aging cavalry unit and was reflective of the fact that the men of STS-6 were the sixth (“F”) shuttle crew, as well as honoring their military heritage. Weitz even had tongue-in-cheek photographs produced, including a crew portrait with the quartet clad in Civil War attire: cavalry hats, braces, red and white neckties, swords, a Winchester lever-action rifle, a bugle, and a flag, emblazoned with the legend “F-Troop.” (According to STS-6 Mission Specialist Don Peterson, the sword once belonged to a lieutenant in Napoleon’s army.) Another image of the crew had them wearing vintage spectacles. In truth, the aged cowboy image was appropriate, because Weitz, Peterson, and crewmates Karol “Bo” Bobko and Story Musgrave were the oldest spacefaring crew to date, with a combined age of 191 years! Behind their backs, other astronauts snickered that they were “The Geritol Bunch”—after the dietary supplement famously associated with aging—but Peterson, for one, did not remember that nickname with as much fondness. “Maybe that was something everybody said about us when we weren’t around,” he told the oral historian, “but when we were in orbit, somebody was talking about ‘how old you guys are’. We had a bunch of F-Troop pictures and I couldn’t resist, so I said, ‘We’re not going to show these to anybody under 35 when we come back! You wise-asses won’t see them!”

When he was assigned to STS-6 in March 1982, it seemed inconceivable that Peterson and fellow Mission Specialist Musgrave would prove to be the first men to perform an EVA from the shuttle. The problems encountered by STS-5 crewmen Bill Lenoir and Joe Allen changed all that, and in late November 1982, Flight International reported that it was “likely” that the EVA would be rescheduled to STS-6. NASA was well aware that the new space suits needed to be thoroughly tested in readiness for the Solar Max satellite repair—an ambitious shuttle mission, scheduled for early 1984—and it was decided to defer Lenoir and Allen’s EVA to STS-6. According to NASA, the addition of the spacewalk caused the STS-6 mission to be extended from an original two days to five days.

“It didn’t give us much time to train,” Peterson recalled. “I didn’t have much experience in the suit, but the advantage was that Story was the astronaut office’s point of contact for the suit development, so he knew everything there was to know. He’d spent 400 hours in the water tank, so he didn’t really have to be trained!” By his own admission, Peterson’s EVA training “was pretty rushed.” He recalled being underwater on a mere 15-20 occasions. However, the tasks for their excursion were relatively straightforward evaluations of the performance of the suit and of the airlock; if any of the equipment tests went awry, he and Musgrave could quickly curtail their spacewalk and return to Challenger’s cabin.

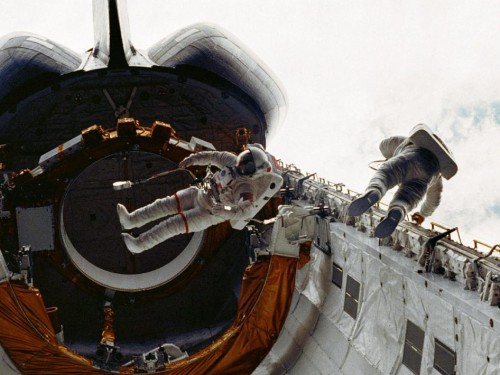

For the spacewalk on STS-6, Musgrave would take the lead as “EV1,” wearing red stripes on the legs of his suit, and although it was scheduled to last for barely four hours, the preparation and conduct of the excursion consumed the crew’s entire working day on 6 April 1983. Aided by Pilot Karol “Bo” Bobko, who would choreograph the spacewalk, Musgrave and Peterson rose early that morning to begin readying their suits and equipment in Challenger’s airlock. They spent three and a half hours “pre-breathing” to avoid an attack of the bends and clear dissolved nitrogen from their blood.

Since reaching orbit, two days earlier, on 4 April, Weitz, Bobko, Peterson, and Musgrave had repeatedly checked their equipment for the long-awaited EVA: testing a third, “spare” upper torso in accordance with flight rules, verifying that oxygen regulators and fans operated normally, inspecting for leaks and confirming that communications were satisfactory. In fact, the only problem raised was a need to replace some flat floodlight batteries. With everything in place, suit donning began and, in true F-Troop fashion, it ran as crisply as a military campaign. At length, at 4:05 p.m. EST, Musgrave initiated the final depressurization of the airlock and, 16 minutes later, pushed open the outer hatch into the payload bay. The plan called for three hours of activities, but he and Peterson had up to six hours’ worth of consumables. Entering the overwhelmingly floodlit bay for the first time, one of his first comments, somewhat understatedly, was that “it’s so bright out here!”

Their time outside may have been limited, but the experience would remain with both men for the rest of their lives. “You remember little things like sound,” Musgrave told a post-flight press conference. “Even though there’s a vacuum in space, if you tap your fingers together, you can hear that sound because you’ve set up a harmonic within the space suit and the sound reverberates within it. I can still ‘hear’ that sound today. But the main impression is visual: seeing the totality of humanity within a single orbit. It’s a history lesson and a geography lesson; a sight like you’ve never seen.”

The spacewalkers’ first task was to tether themselves to slidewires running along the sills of the payload bay walls (one on either side, to prevent mutual interference) and move towards the aft bulkhead, in the process evaluating their ability to handle tools. During the spacewalk, the slidewires were used as part of a safety procedure to prevent Musgrave or Peterson from inadvertently floating away from the shuttle. Meanwhile, the two men began conducting their first “real” evaluations of the new suits: their comfort, dexterity, ease of movement, and the performance of their communications and cooling systems and the payload bay floodlights. One of very few concerns expressed by Peterson after the mission was that “the gloves are hard to work in—extremely stiff—and I had to get my hands strengthened with a little hand exerciser.” Despite this, both astronauts reported that the suits’ mobility enabled them to satisfactorily accomplish each of their tasks. Most of their work focused on identifying suitable locations from which future spacewalkers could best work on the malfunctioning Solar Max, and on practicing some of the intended repair techniques.

This kind of work was essential, not only for the successful reactivation of the $240 million solar observatory, but also for future servicing missions to the Hubble Space Telescope. Musgrave and Peterson finally evaluated the manual system for closing Challenger’s payload bay doors in the event of a failure. This involved using a hand-operated winch, attached to the forward bulkhead, and was performed both with and without foot restraints. It was during tests of the winch line that they encountered difficulties. “Story got the rope hung over something,” Peterson recalled, “and couldn’t release the winch. It was under a lot of tension. There was some talk about how we could get this thing loose so we could get it restored. We couldn’t just leave it where it was because it was on the rollers that were used to latch the doors down.” After the crew’s suggestion to cut the Kevlar line was rejected by Mission Control, Musgrave eventually pried it free with his gloved hands.

At another point during the spacewalk, in what NASA labeled a “high metabolic period,” Peterson received a “high O2 usage” warning on his chest display. Although the message cleared quickly and did not recur, it was attributed to flexure within the suit and his high work rate. “I stopped and said ‘I’ve got an alarm’,” Peterson recalled. “Story stopped what he was doing and came over. We were trying to check what was going on and the seal popped back in place and the leak stopped. Now, in those days, we didn’t have constant contact with the ground. They weren’t watching at the time that happened. By the time we dumped the data from the computers to the ground that showed the leak, we were back inside the orbiter.” It seemed that Peterson’s alarm was caused by overworking and breathing excessively rapidly; this depleted his oxygen, forced a higher feed level, and triggered the warning. Biomedical data confirmed that his heart rate was around 192 beats per minute whilst cranking the wrench, but Peterson doubted he could have worked so hard as to breathe enough oxygen to set off the alarm. In spite of the problems, both Musgrave and Peterson clearly savored the opportunity to venture outside the vehicle in orbit.

After returning to the airlock, the data on Peterson’s alarm was pored over by flight controllers with dismay. “They were upset about it,” he said later, and, this being the suit’s first outing in space, the astronauts would almost certainly have been directed back to the airlock had the problem occurred whilst in communication with Mission Control. At the time of STS-6, however, the shuttle still relied heavily on a network of ground stations to relay its communications and data traffic during part of each orbit, typically only 20 percent. It was therefore ironic that on STS-6, which, in Peterson’s mind, benefitted from having gaps in communications with the ground, the first in a series of huge Tracking and Data Relay Satellites (TDRS) had been deployed to improve communications with future shuttle crews. It was optimistically hoped that, after the launch of a second, identical satellite on STS-8 later in 1983, it would be possible to talk to crews not only during the majority of their orbital time, but also throughout re-entry, eliminating the radio blackout normally experienced during this phase of the mission. Moreover, the existing network of 20-year-old ground stations, which were capable of supporting barely one or two spacecraft at a time, could be retired to save money. Once in place, the TDRS network was expected to be capable of supporting the shuttle and up to 26 other satellites simultaneously.

So it was that the men of STS-6—notwithstanding their ages—contributed enormously to the future of the shuttle program and the future of NASA’s space exploration program. For without Musgrave and Peterson’s EVA, the increasingly complex future steps in spacewalking, such as the repair of Solar Max, the servicing of the Hubble Space Telescope, and the assembly of today’s International Space Station, would have been rendered far more difficult. Without TDRS, the crews of the shuttle and station would be severely limited in their ability to transmit voice and data back to Earth … as would numerous other critical scientific satellites in orbit. The “Geritol Bunch” opened up the shuttle’s capabilities to three decades of remarkable accomplishment … and set humanity on a path to the future.

This is part of a series of history articles, which will appear each weekend, barring any major news stories. Next week’s article will focus on Vostok-1, the historic voyage of Yuri Gagarin in April 1961, which began our species’ adventure in space.

THESE ARE SUCH GREAT STORIES & WONDERFUL ACCOMPANYING PICS!!!

Thanks, Ben! Terrific article – brought back a lot of memories. I was fortunate to work this mission in support of the planned EVA. Terrific success on the heels of the STS-5 disappointment. I remember Story getting up “extra early” that day. Lots of excitement upstairs and on the ground. Cheers!

Beautiful article Ben. So readible, accurate, detailed–wonderfully historic. Had a great time reliving a great moment. Thanks so much for your contribution to this effort. I look forward to reading more of your articles. Thanks so much,

Story Musgrave EV1, STS-6