Thirty-five years ago today, the voice of launch commentator Hugh Harris exulted “Americans return to space” as shuttle Discovery severed the shackles of Earth and took flight. Her mission would run for four days and deploy a large Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS), but its true significance was more profound. For STS-26 was the first shuttle flight after the loss of Challenger, bringing to an end 32 months of grounding and laying to rest the ghosts of STS-51L’s lost crew.

On 28 January 1986, NASA and the United States endured one of the darkest days in its history, as the shuttle—widely touted as the spacefaring equal of an airliner—proved its fallibility in devastating fashion in the skies above Florida’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC). Challenger exploded nine miles (15 kilometers) above the Space Coast, torn apart as the direct consequence of a known fault with her Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs), which allowed hot gases to bypass two sets of rubberized O-ring seals.

Over the next two years, booster manufacturer Morton Thiokol redesigned and recertified the SRBs, whilst NASA attended to critical areas of the shuttle itself: the main engines, brakes, tires, the need for pressure suits to furnish astronauts with better physical protection and implementation of a rudimentary escape system. It was obvious that the shuttle was of too “mature” a design for a comprehensive escape system to be incorporated for the whole crew, but a curved telescoping pole was added to extract astronauts from the crew cabin in controlled, gliding flight in an emergency.

In January 1987, the crew for STS-26 was named, targeting a launch in February of the following year. Commanding the flight was Rick Hauck, who previously led the dramatic retrieval of the stranded Palapa-B2 and Westar-VI communications satellites and piloted STS-7, whose crew included the first American woman in space, Sally Ride.

Joining Hauck was pilot Dick Covey and mission specialists Mike Lounge, Dave Hilmers and George “Pinky” Nelson, who boasted prior five shuttle flights between them. At the time of Challenger’s destruction, Hauck, Lounge and Hilmers were months away from deploying the Ulysses solar probe on STS-61F and the fact that they remained together for STS-26 is hardly surprising. STS-61F’s pilot, Roy Bridges, returned to the Air Force, to be replaced by Covey, with Nelson added to round out a five-man crew.

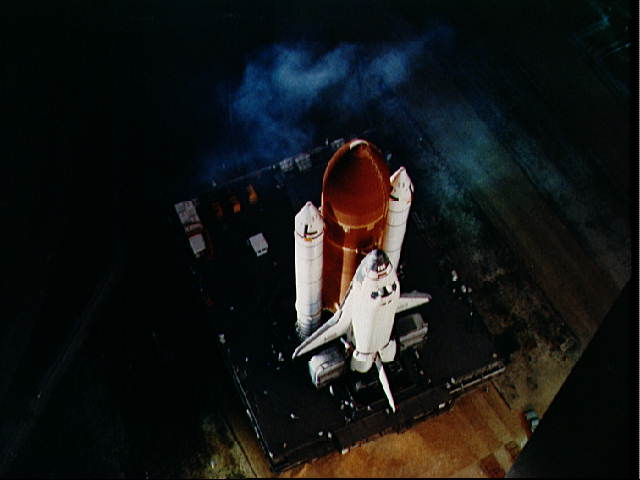

But as with any mission flying after an accident, STS-26’s launch date slipped inexorably to the right and Discovery did not roll out to KSC’s Pad 39B until 4 July 1988. Shortly before rollout, a tiny leak, deep inside the port-side Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) pod, was detected, but repaired at the pad.

On 10 August, the shuttle’s three main engines were successfully test-fired and the TDRS payload was loaded aboard Discovery later that month, as NASA teams zeroed-in on an opening launch attempt on 29 September. The 2.5-hour “launch window” for that day extended from 9:59 a.m. through 12:29 p.m. EDT.

Launch day itself, 35 years ago this morning, was calm and warm, which Hauck recalled lucidly. However, none of the crew confidently expected to go on 29 September, for radiosonde balloon soundings indicated upper-level wind conditions which threatened to pose a constraint to launch.

Although Discovery’s flight software had been configured to “fall” weather expectations, with wind-speed estimates of 28-34 mph (45-54 km/h), conditions actually proved much milder, at 11 mph (17 km/h) from the northeast, more akin to springtime. Reprogramming the shuttle’s computers to accommodate this new condition took two days and the likelihood of flying on the 29th seemed bleak. Yet the five astronauts awakened, showered and breakfasted that morning, then donned their pressure suits and headed out to the pad.

There, the closeout crew presented them with a number of “gag” bon voyage gifts, including expanding, goggle-eyed glasses, which diffused some of the morning’s tension. Aboard Discovery, three-amp fuses feeding power to cooling fan motors to Covey’s and Lounge’s suits failed and needed replacement. By 10 a.m. EDT, the weather outlook began to brighten and STS-26’s chances of flying appeared to soar.

Watching the proceedings from KSC’s bleachers and causeways were an estimated 250,000 spectators, together with 2,500 media and contractor public relations representatives, marking the second-largest for any shuttle flight in history, after STS-1. At 11:28 a.m. EDT, Launch Director Bob Sieck polled his team for a final status update.

As Hauck’s men listened over the air-to-ground communications link, they expected a “No-Go” status on the basis of high-level winds but were surprised when consent was given for STS-26 to go. Covey activated Discovery’s three Auxiliary Power Units (APUs) at T-5 minutes and the astronauts closed their visors shortly thereafter.

A momentary glitch inside the final minute, which almost threatened to halt the clock at T-31 seconds, proved groundless and the countdown continued. For the astronauts, getting off the pad was a welcome relief. Lying on their backs, legs elevated, for over two hours was a long and comfortless slog. “We were still using the urine-collection devices,” remembered Covey, “and those aren’t particularly comfortable or easy to use.”

Finally, at T-31 seconds, control of the countdown was handed off from the Ground Launch Sequencer (GLS) to the shuttle’s on-board computers and at T-6.6 seconds the process of igniting the three main engines got underway. With crisp perfection, the shuttle flexed her muscles and at 11:38 a.m. EDT the SRBs ignited—to an excited “And liftoff…liftoff…Americans return to space, as Discovery clears the tower!” from Harris—and the first crewed U.S. space mission in almost three years was underway.

“No matter how many times you ride this rocket, you’re always a bit taken aback by the ignition of the solid rocket motors,” Covey remembered later. “It’s quite a ride.”

Ascent was nominal, save for a few minor issues, outlined in NASA’s post-flight anomaly report. A gaseous oxygen flow control valve on one of the main engines took a little longer than expected to open and an APU transducer failed.

However, as the crew and spectators ticked off the milestones of flight, the major psychological barrier was crossing the 73-second threshold at which Challenger had been lost. When the fateful “Go at throttle up” call came from Capcom John Creighton in Mission Control, Hauck responded—perhaps not wanting to mimic his predecessor, 51L Commander Dick Scobee—with a clipped “Roger, Go!”

Years later, Covey remembered looking at the instrument panel as the Mission Elapsed Time clock ticked past T+88 seconds. “We’re all kind of thinking about what happened the last time the Space Shuttle had gotten to that point,” he noted, grimly. The twin SRBs separated on time and Discovery flew onward for a further six minutes, until Main Engine Cutoff (MECO). At 11:46 a.m. EDT, precisely on time, the sound of the engines died and the ghosts of Challenger was finally laid to rest.

And a new era for the Space Shuttle began.

2 Comments

2 Pings & Trackbacks

Pingback:“Happiness Is…”: Remembering STS-34 and Galileo, OTD in 1989 - AmericaSpace

Pingback:“Happiness Is…”: Remembering STS-34 and Galileo, OTD in 1989 - SPACERFIT